LOS ANGELES—A film festival featuring new work is a testing ground. After years of arduous effort, a director and a film production company are ready to release their latest magnum opus to the world and hear what audiences and critics honestly think. Some will get picked up for distribution, while others may languish for a while in search of a public and perhaps disappear from view. The recently concluded Los Angeles Film Festival (LAFF) premiered a plethora of features and documentaries worthy of note. Let’s look at one of each under the rubric of “finding-yourself life journeys.”

Just in time for LGBTQ Pride month and Father’s Day, the new documentary Abu by Arshad Khan recounts an Indian-Pakistani-Canadian Muslim family story, concentrating on the tension between father and son over a growing religious and cultural abyss, and focused around Arshad’s gayness. “Abu” is the Urdu word for father.

In retrospect it all makes sense that Arshad, one of six children born to Abu and Ammi, should grow up to become a filmmaker. Abu and Ammi were a Muslim couple from Samana in the Punjab caught up in the mass population exchange in 1947 once India (primarily Hindu) and Pakistan (primarily Muslim) separated and became independent from Britain. Abu became a military engineer, and was always the first in his neighborhood to introduce the latest in video technology. As a result, the family amassed volumes of video and later digital resources. A documentary film using this vast material was simply sitting there waiting to be made.

Among the images captured by various family members holding the camera were many extended family music and dance parties, weddings, birthdays and excursions. Little Arshad gamely kicks up his feet to the latest music, both Western and Pakistani, and is seen donning his sisters’ scarves and outfits for a dress-up party. In their class, milieu and time there was close intermingling of sexes and no prohibition against music or dance.

In their culture, members of the Khan family place high importance on dreams, omens, and predictions. Abu learns that Arshad and one daughter are destined to bring either great shame or great fame. Depending on how you look at it, that’s what happened.

Arshad’s romantic awakenings begin as a teenager, but there is no one he can talk to about his experiences and feelings. This is a repressive culture. Yet it also comes out that he had been molested as a child, more than once and by several people, and from then on, he believed, sex meant men. The theme of abuse returns repeatedly: In a culture where physical contact with other people outside of marriage or the walls of the family is strictly forbidden, sexual expression will inevitably twist into unwelcome forms with lasting impact.

Although Khan does not go deeply into that question, he does speculate that fundamentalist Muslim ideology, of the kind his parents embraced once they had emigrated to the Toronto area, gave a kind of solace, security and certainty, with rigid rules and unbending judgment, to people whose lives had been disrupted and who now found racism, discrimination, and a lot less opportunity in their new land than they had imagined. The film contains so much in its tight, always fascinating 80 minutes: Not only Arshad’s gradual remaking as an unapologetic gay anti-imperialist Canadian, but also about work, religion, sexuality, colonialism, political history, social mores, migration, fate, conservatism, liberalism, music, culture, modernity, family, friendship, growth and change.

Khan goes beyond the narrative he uncovers in his family footage: He also incorporates clips from classic Bollywood films that reinforce stereotypes and mold ideology, as well as footage from recent travels back to the familial homeland. Make sure you stay to the very end!

Since his graduation from the Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema in Montreal, Khan has made several short documentary and fiction films, and is the director of the South Asian Film Festival of Canada, MISAFF.

Abu is a stunning achievement that uses humor, interviews, and old footage to tell a compelling and ultimately heartwarming story. Now that he is in his early 40s and has his autobiographical film out, it will be interesting to see how his talents will manifest further.

Finding your purpose in life

Sun Dogs, scripted by Anthony Tambakis and tautly directed by Jennifer Morrison, also premiered at LAFF. My guess is that this 93-minute “finding yourself” feature will take off and become a talked-about audience pleaser. Among its several producers is Bert Hamelinck of Caviar Group, whose first U.S. feature was Marielle Heller’s quirky, must-see 2015 film The Diary of a Teenage Girl. This one has the similar draw to an offbeat character whom we wind up cheering for and hoping they’ll land on both feet.

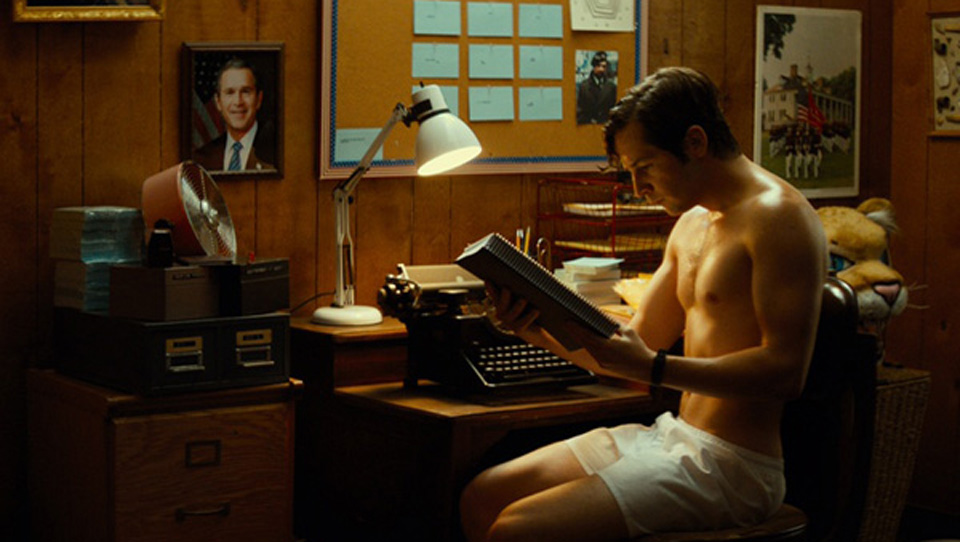

The drama set in 2004 centers on Ned Chipley (Michael Angarano), an intellectually limited young man in the backcountry of San Diego County who has failed time and time again at enlisting in the Marines to achieve his dream of “saving lives.” His mother Rose (Allison Janney) and unemployed stepfather Bob (Ed O’Neill) look after him at home, though he does have high intelligence and many coping skills, if no social graces. He compulsively watches The Deerhunter, imagining himself the servant of his country and savior of humanity. I’m no shrink, and don’t even play one on TV, but I’d guess Ned is a high-functioning Asperger’s case with strong obsessive-compulsive manifestations.

Alvin “Xzibit” Joiner, a multi-platinum rapper, actor and producer, currently starring on the hit TV series Empire, plays Master Sgt. Jenkins, who encourages Ned to “be vigilant” and protect the home front from danger—sleeper cells, terrorists, spies. Ned creates a new persona for himself, a member of the Sun Dogs, and recruits Tally, a young runaway (Melissa Benoist). Their misguided comedic exploits lead to life-changing discoveries about themselves and about the world that also affect Rose and Bob for the better.

The time frame is critical: 9/11 changed life in America permanently, and by 2004 we are already in Bush Jr.’s war in Iraq. The xenophobia, the racism, the fear of the “other” have been ginned up to epic proportions, and hotter heads are behaving irrationally. After a bit of a cooling-off period, now, as a result of the 2016 election, it’s gotten worse again.

If Ned has a sense of his mission in life, he has not yet found the vehicle whereby he can express his purpose, and that is his quest. Director Jennifer Morrison says, “Ned Chipley is right. We all need purpose—mankind’s innate desire to exist beyond ourselves. And like Ned, we’re all misfits in one way or another. We feel misunderstood. We fail. We struggle. We hope. It’s what makes us unique in our search for meaning….

“His journey is the miracle of everyday life. Some things are not what they seem. Some things are much more than we ever imagined. And sometimes, the simplest gesture can make the greatest impact.”

I was struck by the decor in Rose and Bob’s home—the imagery Ned sees every day. There are pictures hanging on the wall, as well as what looks like the wallpaper itself, that depict Middle Eastern and South Asian themes, with appropriate animals such as camels and elephants. Against the background of demonizing all Muslims and Middle Easterners that dominates the news and most conversations, it’s a subtle reminder that the world owes much to the culture and genius of the Fertile Crescent. We should not take those contributions to civilization—like Arabic numbers—for granted.

Tambakis and Morrison have captured the mood of America in those times, which anticipates the hateful, anti-immigrant rhetoric so common today—although if there was any reference, however fleeting, to the antiwar movement of that time, I missed it. Ned’s hyperventilated patriotism is not my cup of brew, nor would it be for most viewers, but the filmmakers make it possible to translate his yearning to be useful with the skillset that he possesses into a universal human drive. The closing credit features the song “Not Alone.” I’m eager to hear filmgoers’ responses to this affecting work once it gets into general release.

A clip from Sun Dogs can be seen here.

Comments