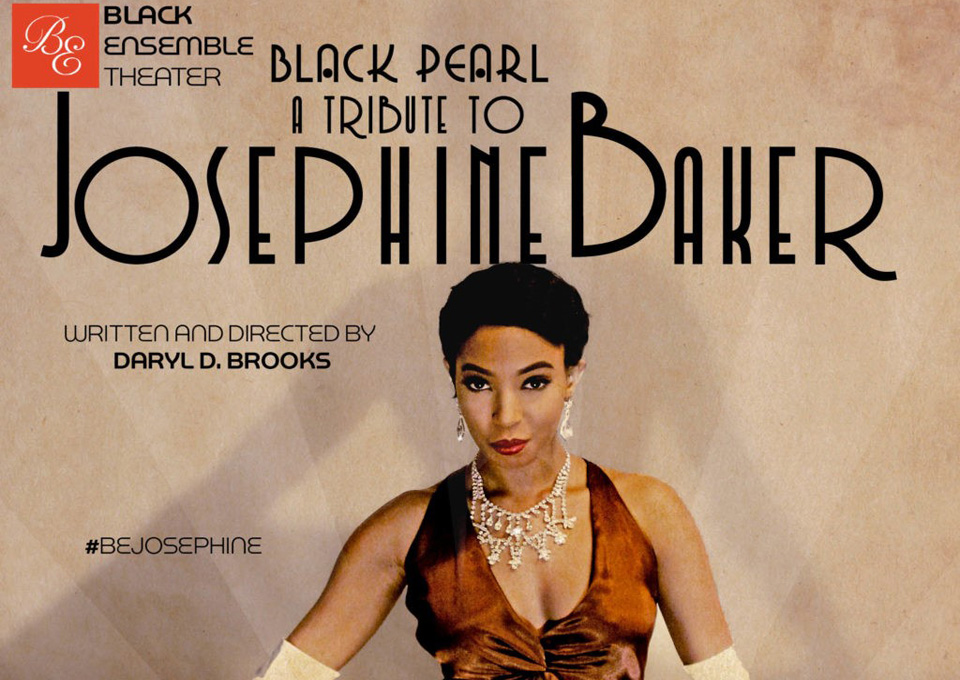

Similar to every production I’ve seen at the Black Ensemble Theater (BET), “Black Pearl: A Tribute to Josephine Baker,” written and directed by Daryl L. Brooks, chronicles American history, and particularly that of African-American politics and experience within that history, through dramatizing the development of African-American musical and artistic expression.

In staging the life of Josephine Baker, Brooks follows in the footsteps of the theater’s founder Jackie Taylor who has produced musical plays on the lives of such artistic stalwarts as Marvin Gaye, Jackie Wilson, Dionne Warwick, and Teddy Pendergrass, among others. Brooks continues the BET’s tradition of exploring the way that music and artists have channeled and given expression and consciousness to an historical, political, and deeply personal experience at once vexed by repression within U.S. society and yet tenaciously vibrant with intellectual and creative energy.

Baker’s career in music and dance provides the perfect subject to underscore the intersection of aesthetics and politics, particularly in African-American cultural history. Her life spanned a good portion of the twentieth century, featuring many moments when she was able to leverage the prominence of her artistic role, both on and off stage, to engage the chief political issues in the American and global scenes. She challenged racism and segregation and took part in the French resistance to Nazism and in the Civil Rights Movement in America, in addition to informing her artistic performances with a political edge. Perhaps nothing more symbolically captures the intimate intertwining of aesthetics and politics than the historical fact that during the Nazi occupation of France, Baker smuggled intelligence reports in her sheet music.

We also see this intertwining in one of the performance’s most electric scenes, the Banana Dance that opens Act Two. The scene portrays the young Baker (Aerial Williams) at the Folies Bergère music hall in Paris in 1926, where she performed a dance wearing little more than a skirt made of 16 bananas (in the play she is clothed).

Historically, this performance marked a major turning point in Baker’s career, catapulting her to wild popularity with Parisian audiences and making her one of Europe’s highest-paid performers. The political edge of the dance lies in the fact that it has a tribal quality informed by African rhythms, featuring Baker in her banana skirt and a group of Black male dancers in loin cloths effectively hunting a white man in a safari costume. Similar to the Danse Sauvage she performed wearing only a feather skirt at La Revue Nègre at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in 1925, the Banana dance risks playing upon the French fascination with exoticizing African Americans as primitives or savages, turning them into erotic objects for the titillation of European audiences.

Brooks handles this potentially racially charged issue in the way he represents Baker’s political daring and drive for self-determination in her art and in her life. When she first arrives to perform in Paris, she is hesitant to wear the revealing outfit in which she is asked to perform, fearing repercussion for being overtly sexual. Her partner Joe Alex, however, tells her that in Paris “the female body is beautiful and so is the color of your skin.”

Brooks turns the moment into one more about Josephine’s self-image and empowerment rather than about how European or white audiences perceive or respond to her sexuality and artistic expression. In the play, this powerful performance highlights Baker’s daring in asserting the value of Black and African cultural forms and traditions – and hence of Black identity – against the racist mentalities of European and American colonizing cultures.

While the play counterpoints America and Paris in terms of the intensity of racism, as Baker repeatedly touts that she finally feels freedom in Paris and has become the highest paid performer in Europe, it also makes clear that Europe is not free from racism, as we see on set the sign for La Revue Nègre featuring a stereotypical black face with big red lips. Nonetheless, the play represents how in Paris, as opposed to America, Baker can be judged by the content of her character and talent, such that she can become the highest paid performer.

Indeed, at one point the play represents Baker’s excited return to America in 1936 to perform in the Ziegfield Follies, only to find herself roundly panned and referred to in reviews as “a buck-toothed negro wench.” Later in the play, Baker accepts an invitation post-World War II to perform in America but will do so only on the condition that all the venues at which she performs are integrated. In this sense, the play represents the realm of aesthetic practice as a contested site where one can politically respond to and challenge social conditions as well as one where the unjust values of a racist dominant culture can be enforced.

Brooks’ portrayal of Baker highlights her as a model of how to use one’s talents and prominence not just to achieve individual success but to promote social justice for the collective good. Near the end, the play features a scene of the older Baker (Joan Ruffin) singing “My Way” at Carnegie Hall. Her rendition of this song popularized by Frank Sinatra takes on a very different meaning when sung by an African-American woman who participated in the Civil Rights Movement and marched alongside Martin Luther King. It becomes an anthem to the quest for self-determination, a key value in African-American struggles and decolonization movements by people of color historically.

The older Baker narrates the play from start to finish and provides a way for Brooks to really connect not just various moments of Baker’s journey but to emphasize her legacy and ability to survive and forge her own path even through tragedies and political constraints.

Baker’s story, as Brooks tells it, is one of survival but also of the need to live beyond survival, as the story emphasizes the power and necessity of art in challenging the social forces of repression as well as in accessing our full strength to celebrate and realize our individual potential and collective humanity. In early scenes, we meet Baker’s parents, Carrie McDonald (Kylah Frye) and Eddie Carson (Lemond Hayes), as they perform a Vaudeville song and dance routine of “Billy Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home.” We learn that Baker was brought on stage to perform as a child, igniting her artistic spark, but also that her mother gave up her dream of performing, believing it best to settle down to raise, as she was then called, young Freda Josephine. Carrie then takes on work as a washerwoman to support the family; but after Carson leaves, facing financial hardship, she sends Josephine at age eight to work for a white family, where she sleeps with the dogs and endures physical, sexual, and verbal abuse.

At age 13, she runs away, finding work as a waitress and beginning at age 15 to audition for performance troupes after honing her dance skills on the street and in clubs. In contrast to her mother, Baker does not set aside her dream in favor of pragmatic survival but chases it ferociously to pursue the full life her artistic impulses dictate despite the oppressive racial and class forces aligned against her.

Any political struggle requires a spiritual strength and uplift to keep people moving toward justice. It can’t just be anger that motivates us. We must also be impelled and kept alive by a joyous spirit to create and be fully human. While this play begins with Baker on her deathbed, it marks death as not the end, as we see hers life as a legacy of persistence, of self-determination, and above all of joy in using one’s talents and making culture.

Black Pearl: A Tribute to Josephine Baker is playing at the Black Ensemble Theater in Chicago through June 25.

MOST POPULAR TODAY

Zionist organizations leading campaign to stop ceasefire resolutions in D.C. area

High Court essentially bans demonstrations, freedom of assembly in Deep South

Communist Karol Cariola elected president of Chile’s legislature

Afghanistan’s socialist years: The promising future killed off by U.S. imperialism

Comments