When Emma Goldman—Red Emma—was deported to Soviet Russia during the First Red Scare following World War I, she befriended Lenin’s wife Nadezhda Krupskaya. The infamous anarchist and the wife of the Soviet leader (since 1898) shared intimacies. As the story filtered down from Emma to Sam Dolgoff, “Seems the Hero of the Revolution was less than a hero of the bedroom” (p. 22).

A salacious little tidbit, to be sure, and hardly of importance, but emblematic of the hundreds of individuals whose lives intersected with that of Sam Dolgoff (1902-1990). In 71 bite-sized chapters of Left of the Left: My Memories of Sam Dolgoff, Sam’s son Anatole discusses his father’s relationships with such people, famous and not so well known, as Goldman, her lover Dr. Ben Reitman, Eugene V. Debs, Eugene O’Neill, Carlo Tresca, Ben Fletcher, Louis Raymond, Rudolf Rocker, Federico Arcos, Dorothy Day, Dave Van Ronk, Murray Bookchin, Paul Avrich, and Augustin Souchy, among many others. Over the course of a long life, we see his friends shuttling between anarchism, syndicalism, socialism, communism and religion as the winds of time blew them about—and some staying true to their course, unswerving for decades.

I knew Sam personally, and his wife Esther. In 1977 I was part of a group in Connecticut that organized a 50-year commemoration of the execution of anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. We invited Sam up as our keynote speaker, for he had been active back in the 1920s in the movement to save their lives. I barely recall what he said, but I do remember that he was offended that at such an event we also invited as a speaker Morton Sobell, who had not long before been released from prison as part of the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg case. Sam objected to having any favorable attention conferred on a communist at this “anarchist” event.

I became friendly with Sam and Esther as a budding scholar of anarchist history. In 1978, at the Libertarian Book Club that he led in New York City, I lectured on Brazilian anarchism, the subject of my recent doctoral dissertation. I shared with Sam my impressions of the 1971 World Anarchist Congress in Paris, which I attended with my girlfriend at the time as the two U.S. representatives. I met his friend Augustin Souchy there, a valiant old Spanish anarchist, around whom an ugly feud arose among the different national delegations over whether the anarchists were right or wrong to join with the Spanish Republican government in the fight against fascism.

The anarchists, no less than other political creatures, often reserved their most righteous anger against those factions closest to them—the “betrayers of the revolution” or the “revisionists” or “sell-outs,” whatever term suits you.

“The hardest thing in life is to stand facing the wind,” Anatole recalls his father saying more than once. “That’s what we tried to do, that’s what we did. The whole thing is a crime, a vast crime, and I’ll fight it to my dying breath.”

Sam was uncompromising and unyielding in his anarchist ideology. For example, the Cleveland branch of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was in its day the last remaining local which actually had a bargaining unit with the employer. They accepted the Taft-Hartley loyalty oath as a fact of modern life even as the national IWW rejected it on principle. Anatole sums up, deftly showing how he can honor his father while disagreeing with him:

“I can well understand the Cleveland local’s attitude. To hell with Taft-Hartley. Why let that define you? Sign the damn thing and live to fight another day. On the other hand I can well understand Sam’s objection. Sign the damn thing and you are no longer a revolutionary organization. Sounds good, but Sam’s attitude consigned the IWW to the same fate as the Shakers, who were at one time very well-known residents of Cleveland, Ohio. Ever hear of them? They were a religious sect with many admirable qualities. However, they practiced celibacy and survived by adopting children. Well, eventually they ran out of children and they remained pure to the last Shaker” (p. 317).

In other matters Sam could be equally obtuse. During the civil rights era, Sam questioned the movement’s reliance on the state to enforce integration—better to win over the white working class and unions. Realizing how long-term a project that would be, he later evolved: “The largely white union movement needed an infusion of black militancy more than the blacks needed white union support” (p. 285).

Nor was Sam enthusiastic about the African and Asian countries throwing off the mantle of colonialism, establishing new states, and in his view simply exchanging masters. He was similarly skeptical about the formation of a state of Israel and was disheartened to watch his fellow Jews become the new colonialists.

Sam worked all his life as a house painter, constantly reading and studying, the model of a self-educated worker. In 1972, Knopf published his scholarly Bakunin on Anarchy, which appeared in a British edition and also in Spanish and Italian. In 1974 he published The Anarchist Collectives about the Spanish Civil War. He challenged the idea that the war was only between statist “democracy” and “fascism,” and asserts that, as Orwell also claimed, there was a social revolution in progress. Dolgoff fils, following his father, has no kind words for the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, nor the International Brigades of which they formed part, under the political and military direction of the communists. Yet he goes on to say that the surviving Spanish anarchist militants, in exile after 1939, did courageously ally themselves with the “democratic” nations fighting fascism in World War II.

For many anarchists, World War II was a turning point. Their antiwar position on the First World War separated them from the socialists, most of whom caved in to nationalism and patriotism. But the Second World War was different in character. Some anarchists concluded that their purism be damned, Hitlerism had to be defeated.

In 1976, still loyal to those small anarchist groups that existed in the early revolutionary movement in Cuba, Dolgoff published a scathing critique of the Cuban Revolution, reserving special scorn for his radical friends who became uncritical Cubaphiles.

He was an idealist for a long time too in the labor movement. Self-abnegating even to the point of self-destructiveness, with a visceral hatred of arbitrary authority and the cultish worship of inflated leaders, he never accepted a position where he had the power to hire or fire anyone. He refused to accept unemployment insurance, considering it charity from the state. To him the New Deal, and the new unionism with its contracts, benefits and protections, only tied working people ever more tightly to the state. He dropped out of the painters’ union for a time because of union corruption.

Dolgoff’s loyalty to the IWW lasted a lifetime. When the anarchist movement evolved away from the strict theory of class exploitation to larger—some might say smaller—life-style issues like education, sexual mores and feminism, communes, diet, treatment of animals, consumerism and the environment, Sam always came back to his narrowly defined working-class roots.

Over time, Sam’s kind of labor movement was reduced to a tiny far-left remnant, as the son’s title suggests.

Biography is also in part a form of autobiography, something Anatole freely acknowledges. When discussing those times in Sam’s life that he and his older brother Abe witnessed or were part of, he freely intrudes his own perceptions into the picture. From his vivid descriptions of growing up in such an unorthodox family, we smell the pungent city, its fish stalls and tenements, the horseshit on the street, we cross doorways into cheap Skid Row beaneries and bars, we imbibe the warm tea and often the heavy drink in second-floor anarchist meeting halls.

The book, long in the research and writing, is an act of self-discovery as much as a record of a passionately devoted couple whose heroic, tenacious comradeship affected so many other budding activists. It is indeed, as Andrew Cornell says in his introduction, “the collective biography of an entire milieu.”

On November 11, 1937, the 50th anniversary of the Haymarket martyrs, Sam Dolgoff spoke at their gravesites in Chicago’s Waldheim Cemetery, alongside Albert Parsons’ widow Lucy. Says Anatole, “My father considered himself the direct spiritual descendant of the Haymarket anarchists and all who knew him well had no doubt that he was” (p. 18).

Many readers of this life, including myself, will sit back in admiration of the noble lives of these loyal working-class characters, Sam and Esther Dolgoff, while simultaneously recognizing their views as an impatient distraction from the mainstream working-class demands in their time. They were tireless utopians, with each passing year more isolated from the masses, in a world that needed fixing one bolt at a time. Ultimate, existential questions of the State would necessarily be tabled to another, later day.

Unfortunately, the book contains a great number of typos that could have been fixed by a competent proofreader, and most disastrously, there is no index! It’s a compelling read, but with an index it could have been—could yet become—a far more useful resource. Anatole should have learned that from his father’s 1986 Fragments: A Memoir, a 200-page book with 9 pages of index. If AK releases a second edition, these improvements cry out to be made.

That said, Left of the Left is the kind of book any parent might wish their child to write: knowing and understanding, sympathetic but not idolizing, honest and intimate. Even in disagreement there is no sense of betrayal. Dolgoff portrays a generation, a political environment and type that barely exist any more in hopes that his readers will appreciate something of what they may have missed.

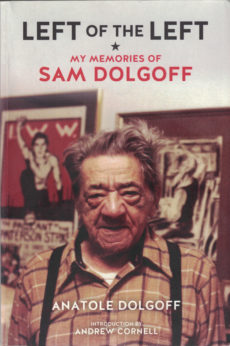

Left of the Left: My Memories of Sam Dolgoff

By Anatole Dolgoff

AK Press, 2016

ISBN: 978-1-84935-248-2

391 pp., with photo album

Comments