DETROIT – I enter the room. A hulking figure, monstrous and grotesquely engaging, walks along a scaffold above my head towards a scarfed, diminutive figure. He wraps his mass around her, then gently kisses her lips. The Elephant and the Dove.

There are no other words that more aptly describe this image dancing before my eyes. I am witness to a magic. A moment when the soul is stirred and the heart is shaken. The vision of how great art, revolutionary art, can change the way we look at the world. I am taking my first step into the world of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit. I am trembling.

The Detroit Institute of Arts has hosted this special exhibit since March 15 of this year. I went on opening day and felt rushed through my first experience. I was the last soul ushered out the door as it closed at 9:00.

I promised myself to go back. Two days ago, in the last week of the exhibit’s engagement, I fulfilled that promise. And, as in the case of love and homemade chili, the second time around was even grander.

I gave myself all the time needed to soak up every nuance of this display, and it was magnificent. I hope some of you readers had the chance to come to Detroit to visit with Diego and Frida. By the time you read this it will be too late.

But still visit our great city and art institute. The murals that Diego painted in the Rivera Court, the reason for this pair’s visit in 1932, will always be here to astound you. And their kisses still echo in that court.

When the Elephant and the Dove came to Detroit in April of 1932 they were three years married. Their respective positions in the art world were at each end of spectrum. Diego was at the height of his career, having recently been given a one man exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Frida, who was twenty years his junior, was just setting out in her career as an artist. He was a renowned muralist and painter, and an avowed radical and member of the Mexican Communist Party.

Frida, who suffered indescribable pain from a bus accident in 1925, shared his politics, artistic sensibilities, and lust for life. Their 11 months in Detroit were driven and tumultuous. As in any manic relationship, there was the roller coaster ride of the great ups and the sickening downs.

Diego worked feverously and created one of the greatest artistic achievements in the modern world, Detroit Industry, while Frida created 11 works of art (seven of which were in this exhibition) to establish herself as a distinct artist in her own right.

At the same time, she was pregnant when they came to Detroit but suffered a miscarriage at Henry Ford Hospital on July 4, 1932. She painted Henry Ford Hospital just days afterward.

In this work, a naked Frida depicts herself on a bed bleeding, with red strings flowing outward from her body, connected to a variety of objects. One string is attached to a fetus, while a tear runs down her face. “I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.”

While Frida despised Detroit, and was neither keen on either Americans nor on their capitalist society, Diego thrived on the industrialism and the technological changes that were reshaping the American worker. He was fascinated by the Ford Rouge Plant and used that as much of the inspiration for the Detroit Industry murals.

This was in the midst of the Great Depression, and Diego was well aware of the ravages that this economic catastrophe had placed on the workers of Detroit. Edsel Ford, the son of Henry Ford, used his own personal money to commission Diego to create the murals.

Diego envisioned that these new technologies could be used for either great social purposes, such as giving workers good jobs with more benefits, or evil purposes. He admired the efficiencies that the Fords had incorporated into the assembly line, but knew of the Fords’ distain for unions and workers’ rights.

In a bold, revolutionary artistic move, he took Edsel’s money and created a complex mural with many subversive proletarian elements secretly embedded in it. He was criticized by his fellow comrades for being a sell out to the capitalists; he was equally criticized by much of the “decent” citizenry of Detroit for bringing communist propaganda to the walls of the Art Institute. Many wanted it destroyed. History has proven that both sides were wrong. The artist prevails.

After Detroit, and a failed attempt to create another revolutionary mural in New York City for Rockefeller, Diego’s career began to falter. But Frida was beginning to find international acclaim. Her stay in Detroit, although filled with disdain and torment, gave her an emotional springboard to soar to artistic heights.

I could feel this in the sketches and paintings, even the simple pencil scratchings, staring back at me from the walls of the exhibit. She painted many self-portraits; of her 143 paintings, 55 are self-portraits. “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.”

As she stared back at me from her paintings, I felt embarrassed for her to see me with a tear rolling down my face. “Be strong, dummy, if she were to see you like this she would probably laugh, then slap you in the face,” I say to myself. She whispers to me, “I was born a bitch. I was born a painter.” I wipe the tear away and blow her a kiss. Nothing back. Not even a wink.

Diego and Frida loved and fought, then fought and loved. They divorced in 1939, then remarried one year later. At their best they lived together in love and joy and harmony and artistic genius, and at their worst they fought with all the piss and vinegar that any couple could muster.

But they fought with, for, and beside each other. The divinely inspired desire to be together for a lifetime, however short or long that may be, is indeed something well worthy of fighting for.

On July 13 1954, Frida Kahlo died at the age of 47. Diego Rivera wrote that the day Frida died was the most tragic day of his life, adding that, too late, he had realized that the most wonderful part of his life had been his love for her.

Her last words in her diary; “I hope the exit is joyful-and I hope never to return – Frida.” You have returned my withered sunflower. You and the Elephant have come back to Detroit. I know you don’t like it here, but it was a nice visit. Now go back home. And by the way, you gonna return that little kiss?

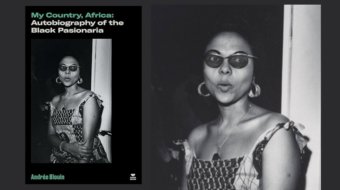

Photo: A painting by Diego Rivera.