Few books capture the dynamism and energy of what is now called the long civil rights movement better than Lindsey R. Swindall’s The Path to the Greater, Freer, Truer World: Southern Civil Rights and Anticolonialism, 1937-1955.

Additionally, Swindall could not have picked two better organizations to illustrate the impact of mid-1930s to mid-1950s struggles for African American equality and Black liberation than the Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC) and the Council on African Affairs (CAA)—organizations both led by members of the Communist Party USA.

The first paperback edition of The Path to the Greater, Freer, Truer World comes at an important moment, as the Black Lives Matter movement continues to grow—drawing attention to the misuse and abuse of police powers—and as interest in socialism reaches levels not seen since the 1930s and 1940s, when the CPUSA’s membership peaked at around 100,000. In today’s politically charged landscape, University Press of Florida and Swindall have done a great service bringing this volume back to print.

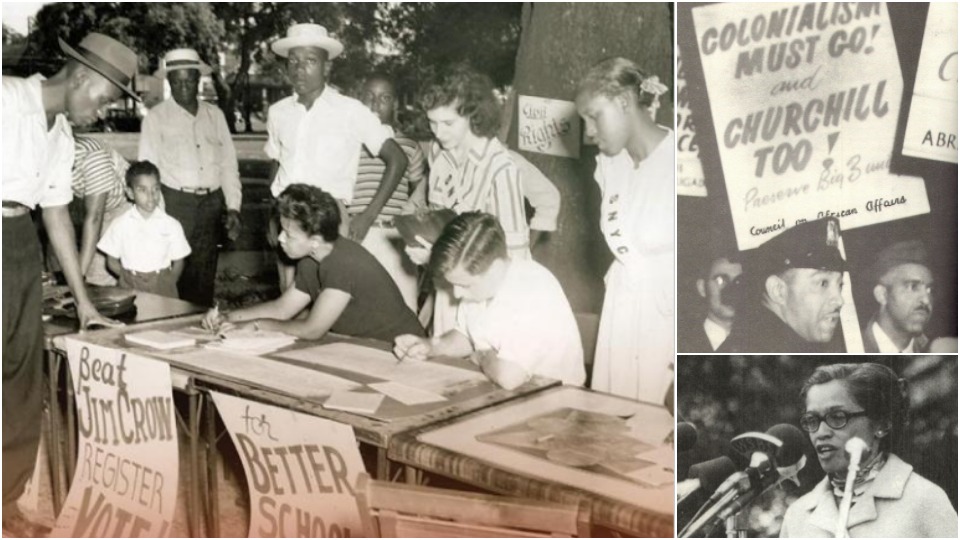

Swindall rightly notes that the SNYC and the CAA were both “examples of the coalition-building that took place during the Popular Front, roughly 1935 to 1939, in which the Communist Party…sought to join forces with liberals, New Dealers, and other progressives to organize for civil rights and labor reforms.”

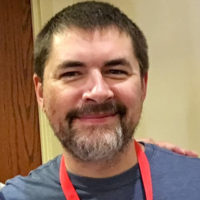

Though the CAA was not founded until 1943, its principal leaders—Paul Robeson, Alphaeus Hunton, and later Louise Thompson Patterson and W.E.B. DuBois, among others—exemplified the Black Popular Front. Theirs was a global vision that supported African American equality, national liberation, and socialism; it was a vision that was at odds with U.S. foreign policy once the war-time alliance with the Soviet Union was broken and the Cold War was initiated, a vision that would find the organization hounded and harassed by the House Un-American Activities Committee and eventually forced to dissolve by 1955.

Illustrating the links between the SNYC, the CAA, the CPUSA, and the long civil rights movement, Swindall quotes Jack O’Dell, a future leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and confidant of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. O’Dell notes: “The great reality of my generation was segregation, fascism, and colonialism. The communists were on my side in all of those things.” As a result, O’Dell joined the Communist-led National Maritime Union, the SNYC, and the CPUSA; though he later distanced himself from the CPUSA, O’Dell continued to associate with individual Communists and wrote for Freedomways, the quarterly journal of Black liberation founded in spring 1961.

Other African American activists—like Alphaeus Hunton, who joined the National Negro Congress and the CPUSA in 1936—made these links, too. As Swindall writes, “The influence of the Communist Party was probably at its height in the African American community during the Great Depression and particularly during the Popular Front period.” Hard-won acceptance of the party’s contribution led thousands of African American activists into Communist-led organizations, such as the SNYC, the NNC, the CAA, numerous CPUSA-led CIO unions, and into the CPUSA itself.

Unfortunately, often overlooked in studies of Black civil rights are the contributions of Black women; Swindall does not make this mistake. Esther Cooper (later Cooper Jackson), factors heavily in Swindall’s analysis of the SNYC.

For example, Swindall accomplishes several interrelated goals when she notes that in May 1942 the SNYC “sent a delegation to Washington [D.C.] to lobby for full integration of black soldiers in all areas of the armed services.” First, she notes Esther Cooper’s leadership in the delegation. Second, she challenges the notion—incorrect, though persistent—that Communists sidelined the struggle for equality during World War II. Third, she links “agitation during the war for desegregation…[to] jobs for black workers in defense industries, and [the] elimination of the poll tax to alleviate disfranchisement of black voters,” particularly in the South.

This is an important acknowledgement, as Communists inside and outside of the armed forces continued to fight for equality during the war. In the various branches of the military, in defense industries, in the unions, and at the ballot box, Communists in broad formations, like the SNYC and the CAA, as well as in the CPUSA itself, fought for equality.

As early as April 1944, the CAA was already beginning a dialogue with officials in the U.S. State Department, with leaders of soon-to-be independent African nations, and with Soviet representatives regarding post-war independence. That month, the CAA sponsored a conference under the theme “Africa – New Perspectives” that included “over one hundred activists, union organizers, educators, and concerned citizens,” as well as representatives from several African nations. The CAA did not wait until the war’s end to begin discussions regarding “a democratic social order and modern economic system in postwar Africa.”

At the conference, Paul Robeson argued that “in order to remain true to the antifascist principles ignited by the war,” Allied powers must apply the “statements made in the Atlantic Charter and at the Tehran, Moscow, and Cairo meetings, which supported the right of self-government…[for] the colonized world.”

The anti-racist, internationalist sentiments, coupled with the SNYC’s and the CAA’s Communist leadership, would soon bring on attacks, though. In 1947, the SNYC was labeled subversive by U.S. Attorney General Tom Clark; by 1949, it was forced to dissolve. A similar fate awaited the CAA, though it persisted until 1955.

The Path to the Greater, Freer, Truer World concludes with a chapter on Paul Robeson’s short-lived newspaper Freedom and its reportage and impact on the civil rights and anti-colonial struggles of the early 1950s. As Swindall writes, Freedom “conjoined the primary impulses of both the Southern Negro Youth Congress and the Council on African Affairs by wedding left-wing battles for domestic civil rights with global campaigns for colonial self-determination.” Additionally, it “assembled a uniquely intergenerational group of contributors” and “engaged activists who wrote about southern civil rights in a global perspective in the early years of the Cold War,” thereby demonstrating the resiliency of bruised and battered—though tenacious—Communist-led left that initiated many of the most important struggles for African American equality and Black liberation in U.S. history.

Linsey R. Swindall’s The Path to the Greater, Freer, Truer World: Southern Civil Rights and Anticolonialism, 1937-1955 is a major accomplishment, and should be required reading—especially today, as the 1619 Project and Critical Race Theory are being debated and in some places banned by Republican state legislatures and governors.

The Path to the Greater, Freer, Truer World: Southern Civil Rights and Anticolonialism, 1937-1955

Lindsey R. Swindall

University Press of Florida, 2019, 238 p.

$24.95

Comments