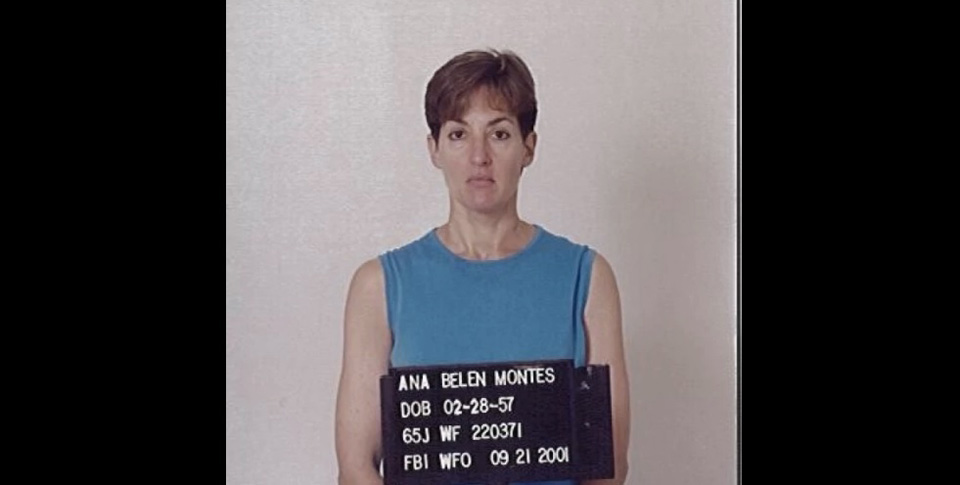

The campaign to gain freedom for 60-year-old prisoner Ana Belen Montes is in need of a boost. Montes, whose family origins are Puerto Rican, is serving a 25-year prison sentence for the crime of relaying U.S. government information to Cuba’s government. Despite strenuous solidarity efforts, mainly by activists associated with movements in solidarity with Cuba and Puerto Rico, prospects for her early release are highly uncertain.

Arrested in September 2001, Montes confessed to relaying U.S. government information to a Cuban handler. U.S. authorities are holding her at Carswell Federal Medical Center, a high-security women’s prison in Ft. Worth, Texas. Prisoners there have psychiatric needs or are facing execution, although apparently Montes has no psychiatric illness.

She worked for 16 years as an analyst for the Pentagon’s Defense Intelligence Agency where she specialized on Cuba. She received no pay from Cuba’s government for her espionage work.

The campaign on her behalf centers on humanitarian considerations. It gathered steam after December 17, 2014 when the last three of the Cuban Five political prisoners returned to Cuba and many Cuban Five supporters turned their attention to Montes. She has gained support through publicity on harsh prison conditions. Indeed, prison regulations prohibit her from receiving emails, packages, and telephone calls; once a week she is allowed to call her mother. Only a handful of people have been able to visit her. Confined to her cell, she is isolated from the general prison population.

In late 2016, Ana Belen Montes learned she had breast cancer. Surgery took place, but little information about her condition and treatment has been available. The British medical journal Lancet recently concluded that,

“Compassionate release programs in the USA are poorly managed” and that “potentially eligible inmates [are] not being considered for release.” Any reforms put in place won’t benefit Montes, though, because even now humanitarian release doesn’t take place until prisoners are at the end of their illnesses.

Lawyers have explored executive clemency as a tool for remedying excessively long sentences. But Montes’ sentence is consistent with U.S. norms. One report speaks of six spies serving shorter sentences than hers, another one reports on five spies serving between 23 and 34 years, and yet another tells of eight convicted spies sentenced to 24 years or more. It turns out that prisoners serving 12 years or less spied for countries friendly to the United States, while all but three of those serving longer sentences worked for Soviet Bloc nations, or in one case, China.

It’s apparent, therefore, that any appeal to precedent or to official guidelines on humanitarian release won’t secure early release for Ana Belen Montes. The possibility does remain of a presidential pardon or commutation of her sentence. In fact, the Constitution gives the president almost unlimited discretion in issuing pardons.

What’s required for that to occur, and for alleviating Montes’ oppressive prison conditions, is a highly visible, united, and powerful upsurge of popular pressure. That’s not on the horizon.

Organizations, political parties, and unions confronting the existing political order are by and large divided and not given to collaboration. And left politics in the United States are at low ebb; funds and people are in short supply.

But there’s more. Potential allies are staying away. The problem seems to be that left political movements or individual activists are focused on this or that single issue. Different struggles have to compete for adherents.

That’s a clue. Whatever might bring activists and organizations together in common struggle promises much for the campaign to free Montes. Anti-imperialism is probably the lead candidate for that role. Imprisoned, Montes demonstrated her anti-imperialist bone fides. As she told her sentencing judge: “I obeyed my conscience rather than the law… I felt morally obligated to help the island defend itself from our efforts to impose our values and our political system on it.” And more: “All the world is one country.”

So anti-imperialism may be the glue bringing people and diverse struggles together. Joined in that way, they’d be ripe for assisting other anti-imperialists already doing the heavy lifting. Anti-imperialist messaging might possibly be a means of bolster propaganda on Montes’ behalf.

This may be the right time, inasmuch as anti-imperialists and anti-capitalists are on an upswing now. Once, when their influence was large, they rescued prisoners. In 1931, racists in Alabama charged nine black teenagers with rape, and sentenced them to die. Over the course of years, political forces beyond that state’s borders orchestrated court proceedings. People abroad demonstrated for their freedom. Amidst worldwide ferment, the “Scottsboro Boys” were saved.

Comments