WASHINGTON – Declaring the world “becomes unnatural if we exclude half of the population,” Chilean President Michelle Bachelet is campaigning hard for “increasing the transformative role of women who get into politics.” And if the only way to achieve that goal is to set quotas for political parties to nominate female candidates – as her nation has done in a new electoral law – then so be it, she adds.

Increasing the number of women in high political office, and in corporate suites, too, is important because “women are able to do much more if they are equal and can be agents of social change,” Bachelet declared in an hour-long talk and question-and-answer session on Sept. 22 at the Woodrow Wilson Institute in Washington. She spoke as part of its series on women in politics around the globe.

Bachelet, serving her second term as Chile’s president, hit that theme hard in her wide-ranging speech. Among other topics, she covered Chilean politics, business and economic development, the “sexism and machismo” women face, comparisons between U.S. and Chilean campaigns, and praise for the recent Colombian peace accord, which includes the rights of women, indigenous people, and LGBTQ people in its text.

Bachelet’s appearance was part of the progressive Chilean leader’s trip to D.C. Her schedule also included meetings with high U.S. officials and a lead role in the Sept. 23 commemorative ceremony honoring the late Chilean Foreign Minister Orlando Letelier and his aide at the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS), Ronni Karpen Moffitt.

Chilean military dictator Augusto Pinochet had his operatives blow up Letelier’s car in downtown D.C. 40 years ago. Pinochet overthrew elected Marxist President Salvador Allende four years before and killed and jailed thousands of his supporters. Letelier, then working for the IPS, a think tank in D.C., was Pinochet’s leading foe.

From prisoner to president

Bachelet was one of those Pinochet had jailed in the aftermath of his coup against Allende. At the ceremony, she received newly declassified intelligence files about U.S. involvement with the Pinochet regime.

Bachelet has come a long way since those days in prison, and she used her Wilson Center talk to urge other women to follow in her political footsteps. She’s one of only thirteen female heads of state and seven female heads of government worldwide.

Women in positions of power, Bachelet said, can make a difference by bringing different perspectives, methods, and goals to the table on issues ranging from child care to “economic development, human rights, democracy, and national security.

“We need to play in real life with a whole team – men and women,” she urged. “It’s impossible to say of societies that they are equal without women at the top.”

By that standard – or even by the lower basic standard of female participation in the workforce – even Chile, along with the U.S. and all other nations, has a long way to go.

Some 48 percent of Chilean women work, up from 38 when Bachelet entered the presidency, but 79 percent of Chilean men work, she noted. And there’s a further tilt: The participation rate is higher among professional women – like herself – who had access to resources, opportunity, and particularly to education than among lower-class women “who really need” such access. And the Chilean Congress is still heavily male, with only 19 women among 120 deputies (representatives) and six women among its 38 senators.

More women in politics

Educating women and girls is the key, Bachelet said, to increasing both opportunity and political participation. But it must be “linked to creativity,” not just learning by rote, she warned: “You can’t just have children sitting and listening to the teacher talk.”

Drawing more women into politics can also improve women economically, Bachelet said. But there are obstacles to women in both fields, particularly “a culture of sexism and machismo.”

Money is another obstacle for women in politics, Bachelet noted – a point that studies have also found in the U.S. A campaign finance reform law she pushed through the Chilean Congress bans corporate campaign contributions of all types. And when she added that breaking the law also forces violators from political activity, the capacity crowd cheered.

“I don’t think it’s good to use so much money campaigning when so many people need so many things,” she added, to applause.

Women also face a political obstacle of being held to higher standards than their male counterparts, Bachelet noted, a condition she said exists in both Chile and the U.S. Bachelet, who spoke fluent and sometimes colloquial English, is familiar with the U.S. system from having lived in here for several years while her father, a diplomat, was posted to D.C.

Women in politics, she said, are expected to hold 9-to-5 jobs and then go home and run the household, too. What society needs, she said, is a change in attitude to equalize the housework roles.

Sexism in the media and society

Bachelet also criticized media mistreatment of women when they are candidates and when they are in office. She discussed the treatment she received while campaigning for the Chilean presidency, coverage of Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton, and the recent impeachment and removal of Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff, a Workers Party member and her friend.

Bachelet said that when she ran for president, she was criticized as “fat” while the mass media ignored her campaign issues and policy proposals. Her larger, heavier, male foe, by contrast, was characterized as “powerful.”

“I’m also mortified by the way the media has treated Hillary,” she said. And while Bachelet couldn’t comment on the legality of the Brazilian impeachment of Rousseff, she added that “I don’t like what’s happened, and I think it’s easier to do” such a removal “when it’s a woman than when it’s a man.”

Besides urging women to enter politics, Bachelet discussed other issues, including the need for education systems to train more women in engineering, science, and math. She also said that capital must be available for women to enter business or train for an occupation.

Chile has such a capital program, but in another indication that “we have a way to go,” Bachelet found when she entered office that the capital was going to women in traditional women’s occupations, such as hairdressing. Her government reoriented the program, so women can enter skilled industry.

Women in Chilean unions face similar sexist obstacles as women in politics and business. “I remember one trade union leader who said to me that ‘The only way they can respect me is if I use swear words.’ But you can do things your own way,” Bachelet replied.

She highlighted the importance of universal and affordable child care for liberating women to rise in politics and business. “If Chile can do it the U.S. can do it, too,” she said. Emphasis on child care is yet another manifestation of how female political and business leaders can bring a different perspective to the table, she said.

Young Chileans, like young voters in the U.S. and Europe, distrust political, business, and religious institutions. Coming from years of the Pinochet dictatorship, they are concentrating on restoring and protecting rights, Bachelet added. But in a phrase that could easily apply to the U.S., she noted that Chilean “young people don’t vote because they don’t think they have a voice.

“But the children of democracy will not accept that,” she stated.

“As a United Nations official said, ‘The empowerment of women and girls is the smartest thing the international community could do to ensure justice and peace worldwide,'” she said.

A video of President Bachelet’s speech and the Q&A session is available here.

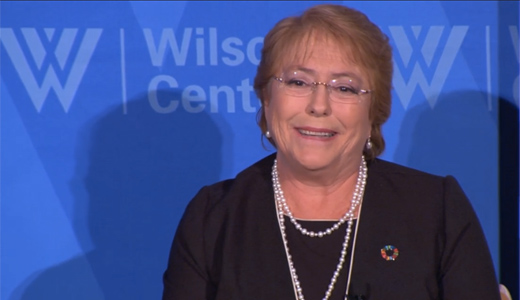

Photo: Chilean President Michelle Bachelet speaks in Washington on September 22, 2016. | Wilson Center

Comments