Bay Area immigrant communities and immigrant rights activists felt they’d won an important victory July 10. At a news conference, Sheriff David Livingston, flanked by the Contra Costa County Board of Supervisors, announced that his department was ending its contract with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to hold immigration detainees in Richmond at the West County Detention Facility, one of the county’s four jails.

Immediately, the organizations that had put pressure for years on the county over its cooperation with ICE demanded the release of the detainees, urging authorities not to transfer them to another location. For the next two months, until the immigrant facility inside the jail was closed, detainees’ families and their supporters mobilized to get legal help, and raise the bond money needed to bail people out of detention. In the end, they raised tens of thousands of dollars and freed 21 of about 175 detainees held inside the center. The rest were transferred.

A final vigil held September 1, after the ICE facility closed, was a bittersweet moment. For seven years, monthly vigils had been held under the portico next to the center’s doors. After the sheriff was forced to abandon the ICE contract, however, activists and families were forced to gather next to a new chain-link fence, in the traffic lane of the highway outside the detention center’s parking lot.

Several former detainees, some freed just days before, came with their families to celebrate. Other families, however, faced the reality that their detained loved ones were now far away, in centers ranging from Adelanto in San Bernardino County to Arizona. Alexa Lopez’s father, Raul, was taken to a facility in Colorado.

“We can’t see him anymore,” said his wife Dianeth.

At the end of an hour of songs, prayers and speeches, the participants wrote messages on white ribbons to those still detained and tied them onto the chain-link fence.

ICE spokesman Richard Rocha accused those who had pressured the county of being responsible for separating families. In a statement when the contract was canceled he said, “Instead of being housed close to family members or local attorneys, ICE may have to depend on its national system of detention bed space to place those detainees in locations farther away, reducing the opportunities for in-person family visitation and attorney coordination.” Immigrant rights activists called that a threat and tried to free as many detainees as they could.

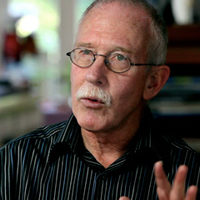

Rev. Deborah Lee, director of the Interfaith Movement for Human Integrity, and the central organizer of the vigils, said the faith groups involved had to examine their conscience. “The transfer of many detainees instead of their release was hard to swallow at first, and many families felt helpless,” she said. “We asked ourselves if we were responsible for their transfer, as ICE accused us. But the families reminded us that ICE moves detainees all the time, and often they don’t know where their own family members are.”

The ICE argument, that forcing the county to divest from cooperation in detention would harm the detainees, is similar to arguments heard during the fight for divestment from apartheid in South Africa. Corporations investing in South Africa at the time said divestment would harm those people who divestment proponents were trying to support.

Opposing divestment, however, was then and is now also a matter of economic self-interest. ICE was paying Contra Costa County $3 million per year to house immigrant detainees. Yet the sheriff didn’t hire any new employees with the money, according to Lee. Instead, his department relied on overtime by the existing workforce. In a petition a year ago detainees complained they were being held in cells 23 hours a day, that there were no toilets in the cells, and that free time for calling relatives or taking showers was often canceled. One detainee asked to be deported in preference to continued detention.

“County jails are the worst place to be an immigrant detainee, even worse than many of the huge privately operated detention centers,” Lee charges. “They have far fewer services for people and aren’t built for long-term detention. Of course, what does that say about the conditions for the non-immigrant people imprisoned there?”

ICE has facilities located in hundreds of county jails around the country, building a dependency among counties on the money paid for housing detainees. The city councils of Hoboken and Jersey City protested when Hudson County, New Jersey, supervisors (all Democrats) voted last July to renew its ICE detention contract. “The county and cities shouldn’t be in the business of profiting off human misery,” Jersey City Mayor Steve Fulop told the New York Times. Sacramento was receiving $6.6 million annually from ICE before it canceled its contract in June. Other contracts have also been canceled in Santa Ana, Virginia and Texas.

The vigils at the West County Detention Facility went on longer than protests at any other county jail. “They created a monthly platform,” Lee explains, “where detainee families could come and ask for support. A consistent, regular event provided a place where people who weren’t necessarily activists could participate. People brought their children, made their own signs, and came to play music. Often one person from a congregation would come at first, and then go back and recruit others. From the beginning, we were committed to the long haul.”

Lee relied on faith congregations as a base, and each month appealed to one of them to take responsibility for the vigil. As the vigils gained momentum and before they were successful, Lee explained why congregations were morally obligated to be involved: “Since the detention center is in our community, we can’t look away. We have to own it, to scrutinize and examine what goes on inside, and be involved with the detainees and their families. Ultimately, we have to force our local authorities to divest and get out of the business of detention, and stop collaborating and making money from it. It’s not impossible. It’s something that people can do to end the detention system.”

Comments