With the spectacular response of the movie “Precious,” this might be the moment that some movies are sending urgent messages to us about a “world war” against women. If we choose to call it a world war then there is a chance that we will become antiwar!

In Chicago, the International Film Festival had an abundance of films to document this war. There were huge differences in the narrative but there was no mistaking the war.

Clarice Precious-Jones is 16 and maybe weighs 300 lbs, lives in Harlem, N.Y., it’s the mid-eighties, and she has two children by her father about 5 or 6 years apart. Because the rape and incest is so hideous, Clarice’s mother attacks Clarice because she has made herself believe that Clarice consciously threatened her relationship with her husband. She didn’t defend her daughter by any means necessary or had him arrested. And isn’t Precious’ weight a defense against sexual attacks?

“Mississippi Damned” directed by Tina Mabry won the Best Picture at the Chicago festival. And just to keep it in perspective this film, based on the director’s real experience as a Black lesbian growing up in rural Mississippi, sometimes makes “Precious” seem tame, if that’s possible. “Mississippi Damned” starts in the mid-eighties and runs until the mid-nineties. The violations here show more than just rape. There’s a conscious effort to suffocate the victim so they’ll never be able to have a thriving life. The heterosexual attacks are no less vicious than the homosexual attacks.

“Fishtank” directed by Andrea Arnold won the Second Best Picture award. The movie is set in the Public Housing Projects of Essex, England. A mother and daughter are seduced by a man who knows the effects of paying attention to women who have never received much attention. They are not aware that he is married and has a young child so when we watch him in his most charming and creepy way, it makes us double sick.

“An Education” directed by Lone Scherfig starts in England where a 16-year-old girl is seduced by a man more than twice her age. Her parents seem to encourage this. The film begs to ask where to draw the line and can a 16-year-old “consent.”

“My Neighbor My Killer” directed by Anne Aghion is a documentary about four days in April of 1994, when 1 million Tootsies, almost exclusively males, were murdered, and many females raped, in the Rwandan Genocide. When you hear the mother tell of her fleeing with one child strapped to her back and one to her front then knocked down, the two children hacked to death after she pleads that they kill her instead of her children.

In at least three interviews, the mothers tell of how dead they are “inside,” ghosts – no feelings. Many were also raped. Which raises the issue of rape as a war tactic that has become so prevalent the UN now includes it as a violation of the Geneva Accords.

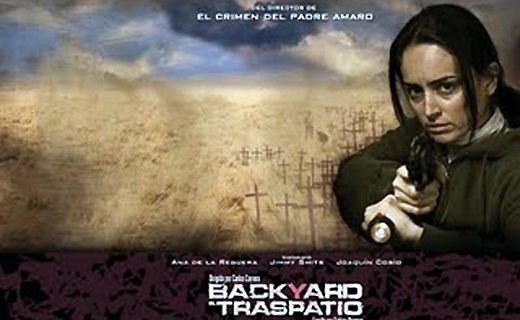

And maybe the crowning conscious world war film is “Backyard,” directed by Carlos Carrera. The film is a dramatization of the thousands of women missing, raped, mutilated and murdered in the desert near Juarez, Mexico-a place where factories were built just over the border so Mexicans could be exploited rather than having to face U.S. labor laws. (Simultaneously, those laws were being dismantled and unions consciously destroyed.) Tens of thousands of Mexican peasants streamed into these factories known as maquiladoras. That was in part due to the NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement), which made sure that even in the tiniest of villages so deep in the mountains where a dialogue of Maya is spoken, not Spanish, and where corn has been harvested for the last five thousand years, all of a sudden couldn’t compete with corn from Iowa.

The story focuses a Juarez policewoman trying both to come to terms and catch the rapist/murderers. At the end of the film we’re seeing real footage of life on Juarez streets. We hear a Mexican rap song about those disappeared and murdered and then imposed on the screen the totals of those dead, year by year.

Then it moves to the U.S., Central America, Eastern Europe and Asia, so we see the worldwide problem. That moment on the screen internationalizes what some might want to argue is a particular condition to Juarez, Mexico. A just plain, slap in the face to facts. What happens to us when we don’t defend and fight for our moms, sisters, and daughters? Aren’t we the ones who have lost our humanity?

MOST POPULAR TODAY

High Court essentially bans demonstrations, freedom of assembly in Deep South

Zionist organizations leading campaign to stop ceasefire resolutions in D.C. area

U.S. imperialism’s ‘ironclad’ support for Israel increases fascist danger at home

UN warns that Israel is still blocking humanitarian aid to Gaza

Comments