LOS ANGELES — An old story tells of a deeply religious man living in his home as hurricane storm warnings are issued. A team of state troopers comes out to advise him to evacuate.

“No need for that, my friends, the Lord will save me,” he says.

As the waters rise to his front doorstep, a dinghy with two rescue workers pulls up and they ask him to step in and come to safety. “No thanks,” he says, “the Lord will save me.”

The waters continue rising. Now he’s standing on his roof. A helicopter hovers overhead with a rope and a basket he can climb into. Again he refuses help: “The Lord will save me.”

The gale sweeps him off his roof and he drowns. He wakes up at the Pearly Gates. “I’ve been your faithful servant all my life, Lord. Why didn’t you save me?”

“I sent out state troopers,” God says. “Then a dinghy and a helicopter. Why didn’t you take my hand?”

Academy Award winner and playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney’s Head of Passes opened Sunday, September 24 at downtown Los Angeles’ Mark Taper Forum, now celebrating its fiftieth season. In two acts set in “the distant present,” it recounts a sometimes laugh-out-loud funny Black family birthday gathering at the well appointed home of Shelah, the matriarch, at the “head of passes,” that is, on a most precarious spit of land at the very mouth of the Mississippi River.

Unfortunately the date coincides with a devastating “act of God,” a violent rain that pounds even through the roof of the house, a torrent that turns into one of the Gulf Coast’s frequent destructive hurricanes. Katrina is not mentioned by name, but that’s the idea. By the end of the first act, this play is no longer a laughing matter.

McCraney’s play premiered in 2016, predating Harvey, Irma and Maria. If anything, these terrifying storms have only gotten worse as global warming proceeds apace.

Shelah (the superb, widely beloved actor Phylicia Rashad) opens the play in supplicating conversation with God. She is a firm believer clearly near the end of her days. The trials of old age, sickness, unworthy children whom she nevertheless forgives and cherishes, not to mention the oncoming deluge, test her spine severely.

Yet she is like the protagonist of the joke: Her unbending faith, her desperate desire to leave her home as a legacy for her three children, her wish that they could come together as a family, at least in mourning after she’s gone, and her contempt for the advice of family, friends and her doctor, all lead her to reject their counsel. She digs in her heels and stays, as the Job-like afflictions mount.

I mentioned to my theatre companion that although people often refer to the heartrending suffering of Job—the result of a cosmic contest between the forces of God and Satan—Job is redeemed with a happy ending for his steadfast belief. “Oh,” he remarked, “they must have added that part later.” For indeed, who wants to believe in a capricious god who plays havoc with people’s lives just for sport?

The point of the joke, it seems to me, is that faith—and salvation, if that’s what you aspire to—is not individualistic. We express our compassion not just in the credos we recite, but primarily in relation to others. Standing fast in obstinate solitude will not save you or anyone else. Shelah is herself a “head of passes”—the family leader who passes on accepting an outstretched hand. If some theatergoers see McCraney’s play as about the “power of faith,” others are equally right to point to its futility, and even the selfishness of it.

Rashad reaches new professional heights in this often poetic and spiritually expansive play, directed by Tina Landau, with whom the playwright has frequently worked at Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre Company. The second act features her in an extended solo turn that rivals, perhaps even surpasses Shakespeare’s Lear raging against the elements. She is joined onstage by a thoroughly dedicated cast that includes Francois Battiste as her son Aubrey, J. Bernard Calloway as her older son Spencer, and Alana Arenas as her daughter Cookie; John Earl Jelks as her houseman Creaker (yes, there is a class system in place way out on this delta), Kyle Beltran as his son Crier, also helping out at the party, Jacqueline Williams as her friend Mae, and James Carpenter as the white Dr. Anderson, who enjoys a familiar, though still racially tinged relationship with his Black neighbors and patients.

While the ensemble acting is delightful—until the whole premise turns terrifying—I recommend, owing to the patois and speed of delivery, that theatergoers employ the listening aids provided at the theatre. I did wonder, given the specificity of locale, why the language did not seem to employ any of the colorful regional Cajun words or expressions.

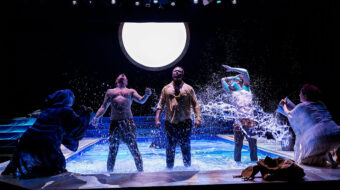

This play relies heavily on production values—rain both outdoors and in, lightning and thunder, a home yielding up its solidity to the unstoppable forces of nature. The scenic design by G. W. Mercier is exceptionally effective, as are Jeff Croiter’s lighting design and Rob Milburn and Michael Bodeen’s sound design. Costumes are by Toni-Leslie James.

I referred earlier to the hurricane as an “act of God,” a manifestation of chaos in the world for which the unseen, unapproachable God is not even accountable. In this sense, I think Head of Passes is already dated. Almost no one now, just a year after the play debuted, or even then, questions the human-induced role of global warming in the catastrophic weather events we are seeing. The play ignores this factor. Indeed, as a central staging area for the gas and oil industry, the Gulf Coast states of Louisiana and Texas have made themselves particularly vulnerable. The bayous and wetlands that protect the mainland are measurably eroding year by year, seemingly with no organized political resistance.

Miami-born Tarell Alvin McCraney has also written the trilogy of The Brother/Sister Plays and Choir Boy, among others, and the original play on which the Oscar-winning film Moonlight was based. At 33 he received a MacArthur “Genius” Grant. He was recently named the new chair of the playwriting department at the Yale School of Drama. Now 36, much is yet expected of him.

Head of Passes plays through October 22 at the Mark Taper Forum at the Music Center, 135 N. Grand Ave., Los Angeles 90012. For tickets and information, please visit CenterTheatreGroup.org or call (213) 628-2772.

MOST POPULAR TODAY

‘Warning! This product supports genocide’: Michigan group aims to educate consumers

Stalin, Zhdanov, Prokofiev, and Shostakovich star in ‘Stalin’s Master Class’

Bad investment: Ohio county treasurer sinks public money into Israeli government bonds

After months of denial, U.S. admits to running Ukraine biolabs

Shawn Fain at Labor Notes: Unions are the arsenal of democracy

Comments