Some women’s lives don’t seem to matter much in the United States. That’s so generally with the lives of expectant and new mothers and with the lives of black mothers in particular. “Motherhood and apple pie” used to be sacrosanct, according to the old adage. Now motherhood is in trouble.

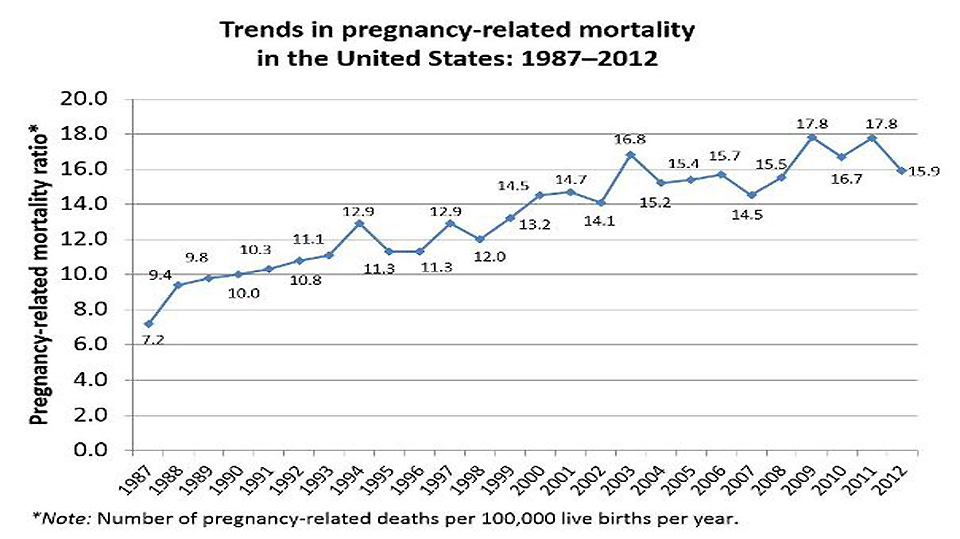

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) documented a rise in the U. S. maternal mortality ratio (MMR) from 7.2 in 1987, to 14.5 in 2000, and to 17.8 in 2011. “MMR” refers to the number of women per 100,000 live births who die during their pregnancy or within 42 days afterwards and who die from causes related to childbirth. According to an article published recently by the professional journal “Obstetrics & Gynecology,” the MMR for 2014 in the United States was 23.8.

Back in 2010, 48 countries had lower MMRs – that is to say, more favorable – than that of the United States; 31 countries demonstrated MMRs of 10 or less. The United States in 2015 ranked 61st in the world in maternal health generally.

Citing World Health Organization data, “Obstetrics & Gynecology” indicated recently that between 2000 and 2013,157 of 183 countries in the world managed to bring down their maternal deaths. From 1990 to the present there’s been a 45 percent drop in MMRs worldwide. Between 1990 and 2014, however, the United States registered increased maternal deaths; its MMR rose 138 percent; from 10 to 23.8.

The news gets worse. The report appearing in “Obstetrics & Gynecology” showed that in Texas the maternal MMR moved from 17.7 deaths in 2000 to 35.8 maternal deaths in 2014. And even worse: data show that black women giving birth face a fourfold greater risk of death than white mothers – whose own risk greatly exceeds international norms.

The Centers for Disease Control reported that while white women for 2012 suffered 11.8 deaths per 100,000 live births, the rate for black mothers was 41.1 The MMR for other minority women was 15.7. In another report, “In Georgia, in 2010, 2011 and 2012, the rate of maternal mortality for white women was 14 per 100,000 live births … For African American women, it was 49 per 100,000.” Yet another study found similar results “even when controlling for age, socioeconomic status and education.” Crucially, “46 percent of maternal deaths among African-American women [were] preventable compared with 33 percent of such deaths among white women.”

What are the mechanisms putting black women’s lives in jeopardy? Many commentators blame the victim and her circumstances; she is obese, for example; lives with violence; uses drugs; has mental health problems; or suffers from this or that other illness.

Systematic discrimination predominates, however. Medical evaluations of African – Americans, for example, are often incomplete and/or incompetent. Poor people, black people included, suffer more illnesses than higher-income people do, including heart disease, which is a leading cause of black mothers dying. Also, “bias, prejudice and stereotyping by health care providers contribute to delivering lower-quality care.”

And black women’s lack of access to health care often causes them to delay medical care during pregnancy, or go without. Either way, they increase their risk of death from pregnancy -related complications. States refusing to extend Medicaid coverage, as provided for under the Affordable Care Act, is today one leading cause of reduced access. The closing down of women’s health-care facilities is another, a prime example being the attack on Planned Parenthood offices in Texas.

Racism therefore is a big contributor to the burgeoning U. S. epidemic of maternal deaths. Discrimination based on social class also plays a role.

In 2010, Amnesty International issued a report that strongly condemned U. S. governmental policies regarding maternal health. Titled “Deadly Delivery, the Maternal Health Care Crisis in the USA,” it insisted that, “Discrimination is costing lives… [W]omen face barriers to care, especially women of color, those living in poverty, Native American and immigrant women.” An Amnesty International spokesperson denounced both a “haphazard approach to maternal care” that is “scandalous and disgraceful,” and a lack of “political will.”

The Amnesty International report indicated women are dying because they are black, or because they are poor, or both. “Women of color are at least twice as likely as white women to be living in poverty,” the report says. It surveyed class – mediated impediments to receiving adequate health care during pregnancy and afterwards. They include language barriers, shortages of health-care resources and specialists in rural areas and inner cities, educational disparities, and lack of insurance coverage due to poverty and, as a consequence, reduced access to health care. Food shortages would be another.

Racial discrimination and class discrimination thus overlap. After all, white women giving birth in the United States are much more likely to die than their counterparts in dozens of other countries. Generally, says the World Health Organization, poor women and rural inhabitants suffer more than their share of maternal death.

A prevailing line of U.S. thought is to belittle the fact of social-class distinctions, and in that vein, as pointed out by critics such as public health expert Vicente Navarro, not a few academicians and officials use race as a proxy for class. Undoubtedly, class dynamics do operate in the current maternal-health catastrophe. But, just as surely, racial oppression is grinding away, taking its toll disastrously and dramatically.

The American Public Health Association was very clear in 2011: “Preventable maternal mortality is associated with the violation of a variety of human rights, including the mother’s right to life, the right to freedom from discrimination.” The Association’s statement quoted Mahmoud Fathalla, formerly president of the International Federation of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. He declared that, “Women are not dying because of untreatable diseases. They are dying because societies have yet to make the decision that their lives are worth saving.”

He was saying, in other words, that women’s lives don’t matter. We agree, especially as regards a capitalist society turning a blind eye to racial oppression and leaving unprotected the most vulnerable women.

MOST POPULAR TODAY

Ohio: Franklin County treasurer attends Netanyahu meeting, steps up Israel Bond purchases

After months of denial, U.S. admits to running Ukraine biolabs

Hold the communism, please: SFMOMA’s Diego Rivera exhibit downplays artist’s radical politics

“Trail of Tears Walk” commemorates Native Americans’ forced removal

‘Warning! This product supports genocide’: Michigan group aims to educate consumers

Comments