“A loving father, brother, grandfather, and friend, our hearts beat with profound loss. It is with profound sorrow that the family of Ramapolo Hugh Masekela announce his passing.”

Jazz legend and anti-apartheid struggle icon Hugh Masekela died on January 23 at the age of 78 in Johannesburg, South Africa. The flugelhornist succumbed to prostate cancer, diagnosed a decade ago, his family said.

“Nelson Mandela’s life-long fight for freedom in South Africa had a secret weapon, music. One of the masters of that music was legendary horn man Hugh Masakela,” Wynton Marsalis once said of him.

Marguerite Horberg, founder and director of Chicago’s legendary world music venue Hot House, where Masakela performed on several occasions, said: “Hugh Masakela was the de facto cultural representative of the ANC. That struggle was titanic and brutal and the exile very tough. His humanity is an inspiration for all times.”

South Africa’s liberation movement paid tribute to Masakela

South Africa’s ruling ANC (African National Congress) said “Bra Hugh,” as he was known, “became the voice and conscience of countless generations of South Africans.

“His anthemic ‘Bring Him Back Home,’ among his many works, spoke of the yearning the South African people had for freedom and liberation.”

The South African Communist Party said Masakela and others “contributed immensely to the international isolation of apartheid and to solidarity with the whole of our African continent and other continents struggling for freedom, justice, and democracy.”

And union federation COSATU (Congress of South African Trade Unionists) said: “Hugh Masekela was not just a musician but was an activist and a hero to many South Africans for using his talent to speak out and fight against apartheid.”

Early life in apartheid South Africa

Ramapolo Hugh Masekela was born on April 4, 1939, in KwaGuqa township, 60 miles east of the executive branch capital, Pretoria, part of a musical household.

Masakela is quoted in a BBC article as saying about his childhood: “You know, everybody had a gramophone. My uncle, he had the greatest voice so he sang along with all the records—Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong.”

His first trumpet was given to him by British anti-apartheid activist Trevor Huddleston, a secondary school teacher later banished from South Africa for his anti-apartheid activities.

“Father Huddleston… met my idol Louis Armstrong and told him about our band. Louis’s response was: ‘Well‚ I got to send them one of my horns‚’ and he did. What this did for the band was get us on the front page of every major newspaper and magazine in South Africa—a first for a black group,” he told TimesLive.

“We knew from when we were very, very young that we were black, and that we were looked down upon by white people.” Masekela told the BBC.

Masakela fled South Africa and lived in exile in the UK and the U.S. for 30 years to study music in the UK and at the Manhattan School of Music in New York.

He received much assistance from another South African musical icon‚ the late Miriam Makeba‚ who was already living in the U.S. She introduced the then 21-year-old to international star Harry Belafonte.

In the U.S., he performed at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 alongside Otis Redding, The Who, Jimi Hendrix, Ravi Shankar, and Janis Joplin. Masekela’s song “Grazin’ in the Grass” hit number one on the U.S. charts. He released over 40 albums during his five-decade career, and worked with artists such as Belafonte, Marvin Gaye, Paul Simon, and Stevie Wonder.

The 1976 Soweto uprising

In banned South African journalist Brian Bunting’s seminal book, The Rise of the South African Reich, he presents a revealing analysis of the origins and development of the Apartheid regime (apartheid is the Afrikaans word meaning separateness).

It traces the mobilization of Nationalist Party power in the 1930s and 1940s around an ideology which had close affinities with that of Nazism. It documents the steps by which the Nationalist Party, having become the ruling party in 1948, consolidated its power: control of the trade unions, banning of mass political organizations, control of education and censorship of ideas, and the building of a massive armed machinery of repression.

He quotes from a pamphlet for indoctrinating the young:

“All white children, Afrikaans speaking-children, should have a Christian-Nationalist education… By Christian we mean according to the creeds of the three Afrikaner churches; by Nationalist we mean imbued with the love of one’s own, especially one’s own language, history, and culture.”

The anti-apartheid struggle had been around as long as apartheid—the South African Communist Party was founded in 1921. But one event seared into worldwide consciousness in the summer of 1976—the Soweto uprising and its brutal repression.

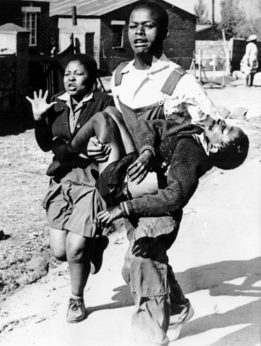

Soweto, a township in the city of Johannesburg, was meant to exist only as a “dormitory town” for black Africans who worked in white houses, factories, and gold mines. The uprising was a series of demonstrations and protests led by black schoolchildren that began on the morning of June 16, 1976. Students from numerous Sowetan schools began to protest in the streets of Soweto in response to the introduction of Afrikaans as the medium of instruction in local schools. It is estimated that 20,000 students took part in the protests. They were met with fierce police brutality. The number of protesters killed by police is usually given as 176, but estimates of up to 700 have been made.

A photo by Sam Nzima (see below) became an icon of the Soweto uprising as it flashed worldwide: Hector Pieterson being carried by Mbuyisa Makhubo after being shot by South African police. His sister, Antoinette Sithole, runs beside them. Pieterson was rushed to a local clinic and declared dead on arrival.

Hugh Masakela wrote “Soweto Blues,” released in 1977 as part of his album “You Told Your Mama Not to Worry.” It is performed by South African singer Miriam Makeba and became a staple at her live concerts. A review in the magazine Musician said that the song had “searingly righteous lyrics” that “cut to the bone.”

Masekela’s son Selema Masekela, a film and TV producer, journalist and musician, is quoted in Variety as saying, “Despite the open arms of many countries, for 30 years he refused to take citizenship anywhere else on this earth. His belief too strong that the pure evil of a systematic racist oppression could and would be crushed…. He carried a deep-seeded belief in justice, freedom and equality for all peoples to the very end.”

Paul Simon and “Graceland”

Upon the announcement of Masekela’s passing, Paul Simon posted on Twitter: “Hugh Masekela taught me more about South African culture and politics than anyone I ever met. A great musician and songwriter, he was also one of the wittiest people I’ve known. I never had a bad moment in his company.”

In 1987, Rolling Stone reported on Simon’s famous “Graceland” tour:

“Special guest star Hugh Masekela, the exiled South African trumpeter, called for the release of imprisoned African National Congress leader Nelson Mandela in his jazz-funk anthem ‘Bring Him Back Home,’ while singer and exile Miriam Makeba lamented the suffering and repression in her homeland with a soulful torching of Masekela’s ‘Soweto Blues.’ And the extraordinary ten-man a cappella choir Ladysmith Black Mambazo awed the crowd with its sonorous bass harmonies and lively Afro-Temptations hoofing.”

However, this was not without a great level of controversy at the time, due to the cultural boycott of South Africa intended as part of the anti-apartheid struggle, as the Rolling Stone article reported:

“As a result of his musical field trip to Johannesburg in February 1985, during which he recorded much of his Graceland album with the cream of South Africa’s black singers and players, Paul Simon has been publicly censured by the ANC and other anti-apartheid organizations in the U.S. and Europe for violating the United Nations cultural boycott of South Africa. Simon’s Graceland shows in England were picketed by anti-apartheid protesters. Several prominent English musicians, including protest bard Billy Bragg and Jerry Dammers (who co-wrote the UK hit “Free Nelson Mandela”) signed a letter to Simon calling for a ‘complete and heartfelt public apology’ for breaching the UN boycott.”

Return to South Africa

Speaking of his life in the U.S., Masakela said: “I used to have a place in Central Park where I would go to talk to my imaginary friends. I was terrified that I was going to lose my language. So I would go there and I would start to speak in Sotho first‚ and I would change from that to Zulu and then to Xhosa‚ and then I would go into tsotsi Afrikaans.”

He knew that he would be able to come home when fellow icon Nelson Mandela was finally released. In 1991‚ Masekela launched his first tour of South Africa‚ which was sold out. From that time, he made Johannesburg his home.

In his 2004 autobiography, Grazin’ in The Grass: The Musical Journey of Hugh Masakela, he frankly discussed his personal struggles with alcohol and drug addiction. He says he had little confidence in his playing without using some sort of drug. But after getting clean and studying about addiction, he said he wanted music to be his only addiction, and he wanted to help his country by improving political and social conditions, including South Africa’s drug and alcohol addictions.

In 2010, Masakela took to the stage with Nigerian singer Femi Kuti (known for both his music and his activism) at the opening ceremony of the football World Cup, held in South Africa—a performance few could have imagined in Soweto just two decades before.

Two years later, he went on tour with his old friend Paul Simon to celebrate the 25th anniversary of “Graceland.”

In October last year, Masekela issued a statement that he had been fighting prostate cancer since 2008 and would have to cancel his professional commitments to focus on his health. He said he started treatment after doctors found a “small ‘speck” on his bladder, and had surgery in March 2016 after the cancer spread.

Masekela also said he felt an “imbalance” and had an eye problem after a fall in April in Morocco in which he sprained his shoulder. He said another tumor was then discovered, and he had surgery.

“I’m in a good space, as I battle this stealthy disease, and I urge all men to have regular tests to check your own condition,” his statement said, asking the media for privacy.

Masekela supported many charities and at the time of his death was a director of the Lunchbox Fund, a non-profit organization to provide daily meals to students in Soweto township.

“My biggest obsession,” Masekela said, “is to show Africans and the world who the people of Africa really are.”

Associated Press and Wikipedia contributed to this article.

Comments