“A great mystery should take ‘the lid off life and let [you] look at the works'”

– Sam Spade, The Maltese Falcon

“The ‘law’ belongs both to the (repressive) state apparatus and to the system of the ideological state apparatuses”

– Louis Althusser, Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses

Ernest Mandel once took time out from his 2,000+ pieces on the economics of long wave capitalist development to note that detectives came from a variety of occupational backgrounds – but with the large exceptions of industrial workers and farmers – “largely because these people do not have the leisure time to be detectives.”

Indeed, for many years, the vast majority of fictional detectives were gentlemen and gentlewomen. They generally used the power of deduction and clue collection to solve crimes (most often murders.) Lord Peter Wimsey, Albert Campion, Roderick Alleyn, Miss Marple, Mr. Satterthwaite, and the great Sherlock Holmes didn’t spend their time in the golden age of mystery drinking with longshoreman and textile workers in Europe to uncover the social conditions that led to the crime happening in the first place (Holmes did occasionally consult with the working class Baker Street Irregular street kids, though not as frequently as the lore often implies.) Sometimes, these “dapper detectives” even solved the mysteries for free, as an intellectual exercise to satisfy their intense curiosity about “who done it?” Several of these characters had fictional aristocratic backgrounds and educations from elite private universities such as Cambridge.

Again, Mandel: “The original detective stories, then, were highly formalized and far removed from realism and literary naturalism. But more than that, they were not really concerned with crimes as such. The crime was a framework for a problem to be solved, a puzzle to be put together…The real subject of the early detective stories is thus not crime or murder but enigma. The problem is analytical, not social or juridical.”

In the era of the pulp magazines, and the novels that followed them, this began to change. As Raymond Chandler wrote in the essay “The Simple Art of Murder” regarding pulp author turned novelist Dashiell Hammett:

“[Hammett] took murder out of the Venetian vase and dropped it into the alley…Hammett wrote…for people with a sharp, aggressive attitude to life. They were not afraid of the seamy side of things; they lived there. Violence did not dismay them; it was right down their street. Hammett gave murder back to the kind of people who commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse…He put these people down on paper as they were, and he made them talk and think in the language they customarily used.”

And as the American and international labor movement became stronger during the Great Depression, more and more private eyes were described as workers…maybe because their often struggling pulp authors felt like that as well. The new “hard boiled” detectives like Sam Spade and Phillip Marlowe talked like ordinary people talked; they didn’t usually get along with the official police; and they often resented wealthy suspects and even their wealthy employers as they worked for their daily fee plus expense checks.

Hammett (a member of the Communist Party who was jailed in the McCarthy era) and Chandler were the premier writers of this genre. Hammett’s brilliant first book Red Harvest may have been the most explicitly pro-working class of his novels in its conceit. Originally published in four parts for the pulp magazine Black Mask, Red Harvest includes a story of a strike breaking industrialist who sees his town being taken over by rival gangsters – the very gangsters he had invited into town to break the Industrial Workers of the World. The majority of the story includes his Continental Op cleaning up the town, but the radical kernel was that the town never would have needed to be cleaned up if not for the corruption of a big industrialist politician to begin with.

But the hard-boiled detective started to shift after the popular front and Allied countries were separated by an Iron Curtain. Private Investigator Mike Hammer became a favorite of political reactionaries including author Mickey Spillane’s friend Ayn Rand (and current graphic novelist Frank Miller, both of whom probably appreciated the black and white morality of the Hammer novels.)

A problem with the more cliché-ridden view of the “hard boiled” tough guy detective is to miss the strong nuanced ethical system that Hammett’s Spade or Chandler’s Marlowe possessed, jumping right to Mike Hammer and embracing the simplicity as a fascistic tough guy medley/pastiche. Mike Hammer didn’t get in trouble with the police because they viewed him as a threat to their jobs like the earlier detectives, but because he would enforce the law through his own violence, which later, as we will see, repeats itself several times in the movies and television. And Hammer was also a brutal misogynist and red baiter, moving quickly against the dual post war threats of empowered women and Communists dating back to the unique circumstances of the war.

And today, you often see a lot of generic “crime first” mystery novels at any paperback book store or on The New York Times best seller list. These stories are frequently ideologically blank and devoid of meaningful acknowledgment of class and focused on forensics and pop psychology (Patricia Cornwell and James Patterson) or of a conservative law and order bent (Tom Clancy) – and solidly entrenched in the aesthetics of the American middle brow. But there is another trend in the detective genres – that of globalization. From South Los Angeles to Sicily to southern France, there is a return to some of the progressive tendencies from the hard-boiled era of pulp.

Walter Mosley’s Easy Rawlins series may be the definitive of these more diverse, international, modern group of detectives, which is especially interesting since the books are set in the 1940s-1960s Los Angeles and have such an attention to local period detail. But Mosley, himself an outspoken progressive and socialist, gives great agency to Rawlins to navigate the contours of race and class. And much like Chandler’s stories, the details of the actual crime are often an excuse for a journey through colorful language and metaphor, though Mosley brings an added element of more intellectual oriented social criticism to his series. For example, his Red Scarlet is at least as effective and intriguing as an expert exploration of the Watts riot as it is a murder mystery.

Grace F. Edwards’s Mail Anderson is also similar to Rawlins in that she takes on a role as sort of the “neighborhood’s detective,” working outside of police officialdom, sort of a hybrid detective-community organizer who hangs out at barber shops, beauty shops, and bars to solve problems by listening to the people.

Jean-Claude Izzo’s Marseilles Trilogy sees a police detective leave the force because of its deep corruption and racism to take on the mob (and their political allies in Marseilles) on his own terms as part of the “Mediterranean Noir” genre.

And in a similar way, Andrea Camirelli (like Hammett, a former Communist Party member, though also with a rich artistic background as would fit an Italian intellectual) uses his Inspector Montalbano series to dump the metaphor of Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui and Hammett’s Red Harvest to directly show how the political corruption and gangsterism of Sicily effect life for a police captain there. His Montalbano is a realistic cynic, but like in the best traditions of Spade and Marlowe, he uses plain language (Sicilian and Italian, which is lost in translation though thankfully there are good end notes to explain some of the unique turns of phrase.) He is a loose cannon, but does not exact vengeance. He’s the ideal protagonist for an author that has a stated goal of tying his crime novels back to “the economic, political, and social context in which they occur…I deliberately decided to smuggle into a detective novel a critical commentary on my times.”

Manuel Vázquez Montalbán was a founding figure of the “Mediterranean noir” genre and his 1981 Murder in the Central Committee features his inspector, Pepe Carvahlo, as the ideal investigator as someone who had worked for both the Communist Party and the CIA. This seems to perfectly encapsulate both the moral grayness and the experience of the political left in the Mediterranean noir genre.

Carvahlo is indeed likely channeling his creator when he remarks “Rich people with a guilty conscience seem to be a thing of the past” – a frequently voiced concern among the diverse left-influenced writers of the crime genres.

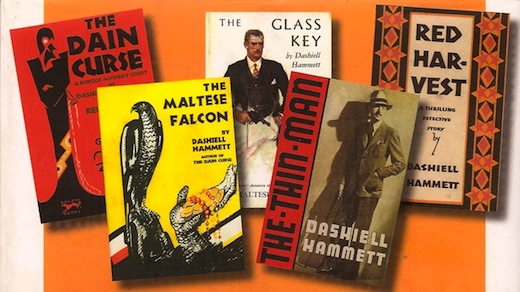

Photo: Books by Dashiell Hammett who is credited with creating the hardboiled detective genre. (via Crime Scraps Review)