The New York City police, on Jan. 13, 1874, overran a demonstration by thousands of unemployed in Tompkins Square Park in the neighborhood now called the East Village.

The demonstration was called in the middle of the so-called Panic of 1873, which was actually a full-fledged economic depression that began in 1873 and lasted for several years.

The demonstration made demands that were advanced, particularly for the time. Workers carried signs saying that charity programs were an unacceptable solution to their plight and that what was needed was heavy government spending on public works programs that would provide jobs for masses of unemployed people.

The workers organized themselves, in December, 1873, into a formation called the Committee for Safety in New York City. The group tried frequently to arrange a meeting with city officials but was turned down after every single attempt.

The workers decided to meet Jan. 13 in Tompkins Square Park and to then march from there to City Hall. The demonstrators planned to insist that then-Mayor William Havemeyer establish a public works program by giving $100,000 to a Labor Relief Bureau to be established by the Committee for Public Safety itself.

Anti-labor newspapers warned of the “menace” the committee represented, spreading the wildest of unfounded rumors, including one that weapons had been bought with jewels stolen in Paris by Communards.

In the end the Committee decided not to have a march but to simply hold the meeting in the park, for which they had already received a permit from the Dept. of Parks. At the request of the police, however, the Department of Parks revoked the permit the night before the demonstration. The move was too late for the masses of protesters who were plannig to attend the next morning. Over 7,000 workers showed up anyway, making it the largtest demonstation New York had seen up until then. Some 1,600 policemen were stationed around the crowd and there were no signs telling people that the permit had been cancelled.

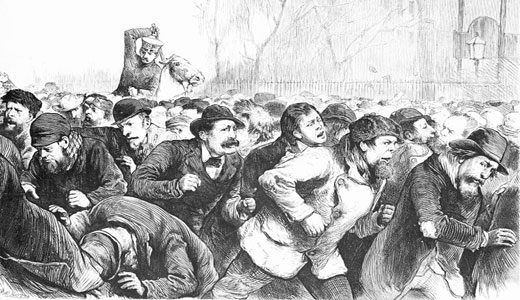

Police charged into the square, dispersing most of the crowds with brutal force, beating thousands with clubs. Police on horseback rode through the surrounding streets also beating people wherever they found them. Hundreds of men, many from the German Tenth Ward Workingmen’s Association, fought back, attempting to defend the people who were under attack.

Samuel Gompers described the events in this way: “Mounted police charged the crowd on Eighth Street, riding them down and attacking men, women, and children without discrimination. It was an orgy of brutality. I was caught on the street and barely saved my head from being cracked by jumping down a cellarway.”

Right wingers spread panic across the city that day. Schools were placed under “police protection” after rumors spread that “immigrants” were planning to burn down the schools. City Alderman Kehr claimed that he had to jump off a streetcar to escape from angry immigrants.

The lies were eventiually exposed and the New York Sun ran a series of articles exposing the complacency of the police and City Hall in the attacks on workers. Unfortunately, however, New York police began a period of stepped-up surveillance of progressive political organizations that was to continue for many years.

Photo: New York police violently attacking unemployed workers in Tompkins Square Park, 1874. Wikipedia (CC)