The new film Louder Than Bombs revolves around a family in distress after the apparent “car accident” suicide by the wife and mother Isabelle Reed, a world-renowned, globe-trotting war and disaster photographer. It was directed by Joachim Trier, and written by Trier with Eskil Vogt, Trier’s English-language film debut. The Norwegian was named one of 20 Directors to Watch by the New York Times in 2013.

The original screenplay is not “based on a true story,” as so much of what we see today purports to be. Yet there is a fictional verity that is often greater than the affecting stories we pluck out of real life and mold to our desired outcome.

In the younger son Conrad’s New York suburban high school English class, a girl reads a passage out loud in literature class. It almost doesn’t matter what it’s “about,” for it gives flight to Conrad’s death fantasies, depressive ruminations, and daydreams, which coincide with certain words in the spoken text. The director seems to be saying that one telling – and one hearing – is as valid as another, it being maddeningly difficult to discern the truth, as if there even is a single truth.

The same incidents are shown on film and then prismatically retold from a different perspective, giving Louder Than Bombs a non-linear Rashomon-like quality. Trier constructs his film like an intricate puzzle, mixing flashbacks with present time, nighttime and daytime dreams, and even narratives from the future, or perhaps from the dead. Voiceovers narrate, but are we sure whose voices we hear? Whose point of view do we take as defining?

Characters in this cinematic kaleidoscope seem like marionettes that Trier dangles from strings of neuroses, fears, uncertainties, doubts and lies. “I find our memories, and our ideas of self and identity based on these memories, fascinating and puzzling,” Trier says. “There is both despair and hope in memories.”

Everyone in this puzzle has their secrets, their little deceptions and pretenses, their outer roles and inner realities. No one can be assumed to be completely honest – not even to just be their authentic self. The widowed husband Gene, now a teacher at Conrad’s high school, is a former actor who, according to his own account, was too good-looking to be taken seriously. He is accustomed to the wearing of masks.

And Isabelle’s photographs tell their own story. The photographer questions her role, her purpose, her motivations, as she tries to win the confidence of her subjects in dangerous places of war, famine, exile and violence. Such a career might appear glamorous to the outside world, but to their partners, children and families, many who devote themselves to such professions, and to movements or even hobbies, are prone to coming home and feeling a little empty, much like our military who often feel they’ve abandoned their buddies at the front. It is, of course, to the writers’ credit that they have made this “breadwinner” role a woman for once, not a man.

The Reeds are a microcosm of the world’s disorder. Mirroring the dysfunction and turmoil thousands of miles away, this family is somehow incapable of seeing the chaos underfoot. Murderous movements portray themselves as ordained by God, military adventures parade as freedom crusades, killing is redefined as honor. Progressive-thinking people around the world often wish a stronger United Nations existed, not necessarily as Big Brother or a One World Government, but as a community – a family – of nations earnestly trying to work out global problems in the interest of most of the people. On this intimate scale we so wish for a successful family therapy resolution.

Conrad, withdrawn and hostile, attracts most of the concern. We can only wonder why was there not more attention paid to such a troubled teenager in the form of counseling, or even plain old empathy? Yet he does have his outlets: He writes a somewhat rambling but magical journal of his inner life. As an adolescent he has yet to learn how to wear the right-fitting mask as the rest of his family has perfected. In the end, with allowances for his present stage of maturation, he may be the most together one of them all.

The film starts off with the older brother Jonah with his wife Hannah in the hospital. She has just given birth to their first child, and he has forgotten to pack her postpartum dinner. Hannah unleashes a torrent of vulgarity, perhaps forgivable for an exhausted, hungry woman, but both his and her actions nevertheless signal that not all is well in this marriage. That’s before we even meet the rest of the family.

The unusual title of the film is explained by Trier: “If you listen carefully, the subtle sounds and nuances of family life can be louder than the more obvious thunder of bombs.”

Well, Conrad seems like he’s going to come around – his ostensibly wise brother says “It gets better.” For the rest of them, it’s possible to imagine them turning a corner in their own lives going forward after learning some hard lessons. And then there’s the passage of time: A lot of it has passed in 109 onscreen minutes.

And now I put my Marxist critic hat on and ask, Is the purpose of art to ennoble? To fix the world? To offer perennial hope to the masses that through struggle (guided by the correct ideological principles, of course) things will get better? Most of the time I think it is, but really I don’t know. There’s plenty of art that is just about art, or that is tragic and cathartic, and that doesn’t make it reactionary. I too at times peer into a fractured mirror.

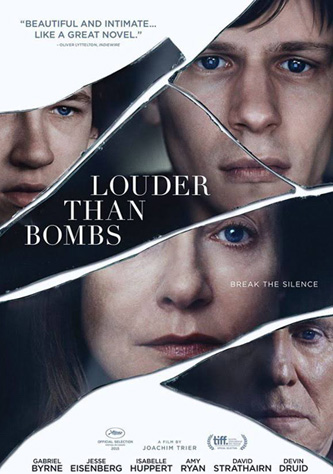

The cast includes Isabelle Huppert as the photographer Isabelle, Gabriel Byrne as the father Gene, Jesse Eisenberg as the older son Jonah, Devin Druid as the younger son Conrad, David Strathairn as Isabelle’s lover Richard, and Amy Ryan as Gene’s colleague Hannah.

Comments