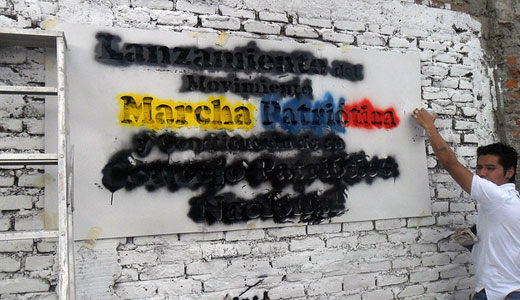

Marchers, 100,000 of them, filled the Plaza Bolivar in the Colombian capital, Bogotá. In 2,500 buses, they traveled from all 28 Colombian departments. They were the “forgotten Colombia, the Colombia of young people, children, old people…men and women whose views were shaped on the land and in adversity.” On April 23, they celebrated the founding of Marcha Patriotica, which aims at integrating social movements and political parties.

Over the two previous days, 4,000 delegates representing 1,700 social and political organizations with two delegates each gathered at a convention center to discuss Colombia’s political situation, outline organizational structures, define tasks, approve a political declaration, establish commissions, and appoint a National Patriotic Council. International guests numbered 130. Plenary session speakers included Carlos Lozano of Voz, the newspaper of the Colombian Communist Party; former Senator Piedad Cordoba, leader of Colombians for Peace; Senator Gloria Inés Ramírez of the Alternative Democratic Pole (POLO); Jaime Caycedo, Communist Party secretary general and former Bogota city councilor; and Marcha organizers. They called for a “second and definitive independence,” structural transformation, and peace with justice. Immediate demands included agrarian reform and access to health care and education.

The movement’s political platform noted “new dynamics of collective action in our country,” and “growing desire [for] exercise of politics linked to the many social and class conflicts.” The document proclaiming a “vocation for power” calls for “political change to overcome imperial domination and hegemony imposed by dominant classes.” Marcha Patriotica is “not simply a tactic of alliances but is a process for building subjective consensus toward unifying the oppressed and exploited classes, our historic task.”

The platform calls for political solution of armed conflict; democratization of society, state, and economic model; alternative ways of life and production; human rights guarantees; “humanization of work”; reparations for victims of strife; land reform and protection of rural people; education for all; a “culture of solidarity and transformation of the social order”; and lastly, Latin American integration, internationalism, and national independence.

Instrumental in launching the new movement were the Liberal Party’s left wing, headed by Piedad Cordoba, the Colombian Communist Party, student organizations, the Fensuagro (United National Agricultural Union Federation) agricultural workers union, indigenous groups like the National Minga, and small farmer groups. Planning started in 2010, the bicentennial year of liberation from Spanish rule.

Other organizations, namely the Patriotic Union (UP) and the Democratic Alliance, each sought left unity in the 1980s, and the relatively recent POLO electoral coalition does so now. POLO suffers presently from internal divisions and weak ties to social movements. Leaders issued a statement supporting the Marcha Patriotica, but POLO stayed away from the inaugural events.

The Communist Party presently supports both the POLO and Marcha Patriotica.

In 1985, the communists joined with the Revolutionary Army Forces of Colombia (FARC) to form the UP, the latter having abandoned armed struggle to enter electoral politics. Now President Juan Manuel Santos, government officials, and the media contend the UP and Marcha Patriotica are alike, each backed by the FARC, also that the FARC has infiltrated Marcha Patriotica. Marcha spokespersons argue the situations are quite different: a peace agreement prevailing then allowed for political collaboration, impossible now under war conditions.

The government bases its claims of FARC associations on evidence allegedly taken from seized FARC computers. Earlier, the Supreme Court discredited similar evidence used against journalists and other left-wing political figures. Soldiers and police throughout Colombia intensively monitored and severely harassed Marcha activists over several months, arresting and tailing many of them, threatening family members, and barging into homes. Security officials impeded travel to Bogota. Intelligence operatives watched over proceedings there, trailed visiting foreign supporters, and photographed participants. Scapegoating the organizers as tied to FARC may testify to governmental fears over the movement’s potential impact.

Relying on paramilitary thugs, the Colombian government intimidates through killings – as evidenced by massacre of 5,000 UP activists. Now, three Marcha organizers are dead, or feared dead. Martha Cecilia Guevara Oyola, community leader in Caquetá, disappeared on April 20. Hernan Henrry Diaz, Fensuagro organizer who arranged travel to Bogotá for 200 Putumayo people, disappeared on April 18. Mauricio Enrique Rodriguez, a communist and bodyguard for the president of the National Association of Displaced persons and formerly for Carlos Lozano, was killed on April 27.

Nevertheless, expectations are high. The Marcha Patriotica political declaration “affirms[s] the existence of collective dreams to lay out routes of dignity, to open doors of hope [for a] new historical chapter, forged necessarily in the broadest possible popular unity.” For Carlos Lozano, Marcha Patriotica “proclaims peace, which we understand as a political solution with peace moving into the foreground of Colombian politics.” Eventually, he adds, “Marcha Patriotica could be converted into a space suitable for guerrillas who welcome a peace process.”

Photo: Marcha Patriótica // CC 2.0

Comments