The First Amendment of the Constitution of the United States of America states: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.”

Those words are a simple act of democracy in which free speech and free press can be guaranteed in a free society, but those guarantees are being eroded by the very person who is essentially the guardian of the Constitution—the President of the United States.

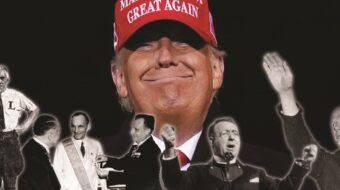

In the aftermath of the U.S. midterm elections, Donald Trump held a rare press conference in which he spouted his own “greatness” and berated anyone who did not agree.

He falsely claimed he enjoyed a high approval rating among African Americans and labelled immigration an invasion. When challenged and questioned by reporters, he turned on them and deemed them “the enemy of the people.”

Since he took office in January 2017, the world has witnessed the U.S. hurtle head first into the Trump world, a world which is hostile to minorities, the press, and the truth.

Twenty-four hours after being sworn in as president, Trump sent White House press secretary Sean Spicer to drill some discipline into the media. Their crime? Reporting the low numbers at the presidential inauguration.

At the White House press room, Spicer went into Rottweiler mode and barked out his insistence that the numbers were much higher than reported.

Although we all saw the poor turnout, either on the ground in Washington or live on TV, the new regime at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue wanted us to believe an “alternative fact.” It was January 2017, and a style of censorship and propaganda reared its ugly head in the “land of the free.”

Censorship and propaganda were fiercely important tools used by many ruling regimes throughout history. Italy’s fascist dictatorship wielded these tools in order to control public opinion of Il Duce.

In Mussolini’s Italy, a special ministry was set up to oversee the control of communication. The Ministero della Cultura Popolare (Ministry of Popular Culture) controlled what newspapers published, what radio could broadcast and what cinemas could show.

One such film that did not pass the test at the ministry of popular culture was Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator. The 1940 film lampooned the likes of Hitler and Mussolini and, of course, it did not go down too well with Der Führer and Il Duce.

Over 70 years later, the very thought of banning a piece of screen satire is considered an extreme act, but satire still attracts the ire of those it lampoons. When Saturday Night Live skewered Trump, he declared his hatred for it and called it unfair.

Mussolini’s ministry of popular culture was one of the most overworked departments in his dictatorship. Its iron fist handed out daily slogans for people to adhere to, such as “Il Duce ha Sempre Ragione” (the leader is always right).

The words that poured out of Mussolini’s mouth were akin to gospel. His powerful nationalism of “Italy first” whipped up a frenzied support base with the aid of censorship and propaganda.

He was portrayed as a macho man who would clamp down on corruption and crime. Mussolini’s propaganda machine even managed to make people believe that he single-handedly made Italy’s trains run on time.

The light was never turned off in his office as a ploy to make people think Il Duce was working hard into the early hours, when in reality he was in bed. Had the technology been around in those days, I suspect he would have been tweeting in bed.

The press in Mussolini’s Italy was instructed on what to report and what not to report. Of the things that were strictly off limits with regards to Mussolini were his birthday and illnesses.

The totalitarian leader wanted to portray a man who never fell victim to sickness or never fell victim to the aging process. He held an obsession with his appearance, and any photos taken of him would have to get his approval before going to press.

Any unflattering pictures showing the dictator’s bulging belly or double chin were either binned or doctored. A double chin problem also plagues Trump who, before taking office as president, summoned media executives to Trump Tower to verbalize his upset with some media outlets who published unflattering photos of his double chin.

Media outlets in Mussolini’s Italy that reported opposing news about the regime were instantly suppressed, while pro-Mussolini media was awarded for its loyalty with state subsidies.

In 1926, a law was passed which saw newspapers needing a special permission from the government to publish anything. This was Mussolini’s style of stranglehold on an Italy he wanted to make great again. He wanted to resurrect the Roman empire with himself at the helm of it, unchallenged and unquestioned.

In those bleak days of European fascism, citizens of totalitarian regimes were told untruths until they eventually believed them or at least accepted them, however reluctantly. Mussolini decreed that Italy was such a hopeless case that it needed a strong man like him to fix it.

A series of bullishly blatant “alternative facts” sent Trump hurtling to the White House and since then, he, and those around him, have continued with those same “alternative facts” to shape their own version of a dystopian U.S.

There is a lot to fear, but there is lot to be optimistic about.

Totalitarian type regimes usually birth a strong resistance to them and that was evident with the Women’s March on Washington the day after Trump’s Inauguration, a movement made possible by the type of rights enshrined in the First Amendment.

And recently, the midterm elections resulted in more young people, more women, and more minorities taking on the fight against Trumpian politics at the polls. People are enraged and engaged, and, as long as they remain so, the First Amendment should survive.

MOST POPULAR TODAY

High Court essentially bans demonstrations, freedom of assembly in Deep South

UN warns that Israel is still blocking humanitarian aid to Gaza

Resource wars rage in eastern Congo, but U.S. capitalism only sees investment opportunity

U.S. imperialism’s ‘ironclad’ support for Israel increases fascist danger at home

Comments