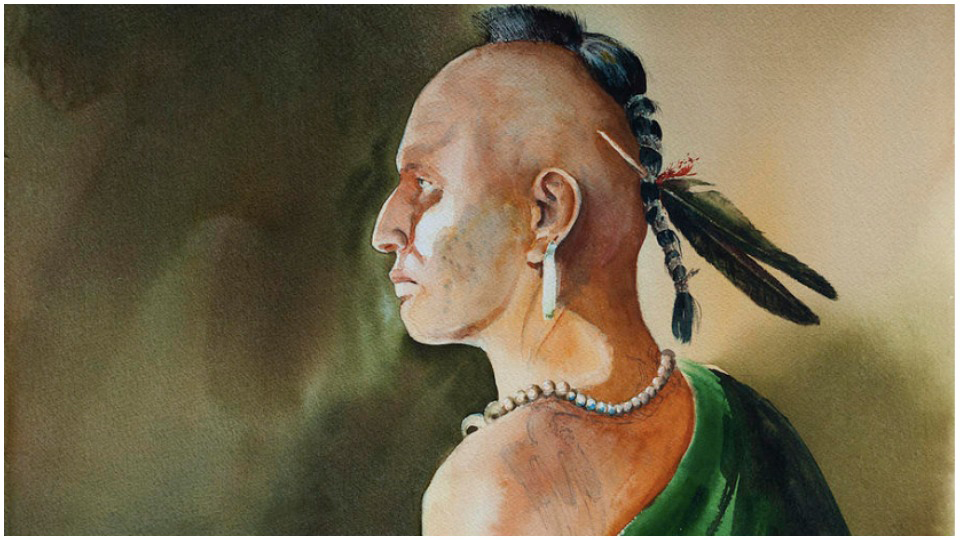

NASHVILLE, Tenn.—“A dark and bloody ground” the great Cherokee war chief Dragging Canoe promised in March of 1775 at the so-called Treaty of Sycamore Shoals to white settlers negotiating for the sale of Cherokee land in what is now Tennessee and Kentucky. His prophetic statement was the precursor of almost two decades of frontier warfare. His memory is legendary in parts of the South that are historically Cherokee. In fact, in East Tennessee and Western North Carolina there are outdoor dramas that depict the history of Indian/pioneer warfare in which he is prominently portrayed. Accounts of his speeches have been referenced by U.S. presidents, and his war strategies have been studied by West Point generals. He is now considered a military genius.

As Middle Tennessee was a focal point for the struggle of the Cherokee people against the settler invasion, it is appropriate that this should resonate in the present day. There is even contemporary speculation that Nashville would not have survived had Dragging Canoe lived past 1792. In this regard the local Indigenous community of Nashville held another “Dragging Canoe Day” on April 7, to honor this indomitable leader.

Some of the remembrance of those embattled times has resulted in an attempt at redemption and reconciliation over the years. For example, in April 2010, in East Tennessee the Carter County government (the descendants of the white settlers who fought Dragging Canoe) passed a resolution acknowledging the tragedy of the broken covenant between themselves and the Cherokee Nation. This was an admission of historical culpability on the part of the settlers and the land speculators that precipitated the long and bloody Cherokee War.

Interestingly, in the course of speaking at different venues in Nashville about Cherokee history, I have met white people who have recounted stories of the Cherokee Wars of the 18th century passed down in their families.

In the Nashville area many battles were fought between Cherokees and settler forces. Dragging Canoe led the Indigenous forces and almost wiped out the first white settlement in Middle Tennessee, Fort Nashborough, in what is known as the “Battle of the Bluffs.” The land of present-day Nashville is soaked with the blood shed in the many grim contests between white settlers and Dragging Canoe’s warriors.

In honor of this great Native resistance leader, the local Indigenous community has for the third year in a row held a commemoration in his acclaim. Indeed, it is becoming an annual event. The theme this year was how Dragging Canoe’s war and the movement he led focused on building unity against the forces of oppression. This perfectly reverberates with today’s struggles.

A gaze into the crucible of history

Let’s take a gaze into the crucible of history to see how the past can resonate in the present with inspiration and lessons to carry forward the never ending struggle for justice, freedom and equality. In the late 18th century one could not travel in what is now Tennessee, Kentucky, Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, or South Carolina without knowing of Dragging Canoe. His sphere of influence and political reach ran from South Carolina westward to New Orleans and from Florida northward to Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan.

The first speaker, Jeff Hobbs, who is Cherokee and African American, emphasized that Dragging Canoe embodied the spirit of resistance and unity. He spoke about the effect of the “peculiar institution” of slavery, in attempts by the colonists to divide Native people and Black people from uniting against their oppression. Whites tried to make “Indian fighters out of Africans and slave catchers out of Indian people.”

But Dragging Canoe welcomed African people who escaped from slavery and those who were captured (or liberated) in campaigns against the settlers. They were incorporated into the resisting Cherokee communities. There were also whites who saw the justice of the Cherokee cause and joined in the fight against settler and land speculator oppression. They too were welcomed by Dragging Canoe.

Hobbs also spoke of how the current Trump administration emboldens and encourages racism, saying that in the face of this upsurge we must follow in the spirit of Dragging Canoe and pursue unity. He admonished that we must all work for the “common good.” Hobbs ended on a cautionary note that with the current administration “the worst is yet to come.”

Next to address the assembly was Lou White Eagle, Southern Cheyenne, who warned that we must be wary of what is called “civilization” and how this concept has historically affected Indigenous tribes from the Southeast to the West. If this so-called “civilization” continues at the current pace, what will happen to the Earth and all the creatures on it?

White Eagle said that we are all still struggling for freedom, trying to break the bonds of government control. There are too many restrictions on the activities of the people of this land. An example is that now there are restrictions on the visiting of sacred Native sites (White Eagle had recently visited the Great Serpent Mound in Ohio). Now we are also fighting for a resource as basic as water, as shown by what is happening at Standing Rock. White Eagle also echoed the sentiment that we should all stand unified in the face of this resurgence of racism. This again resonated in the spirit of unity and uncompromising struggle as exemplified by Dragging Canoe.

It’s only fitting to end this column with a quote from Wilma Mankiller, principal chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1985 to 1995: “To see the future, one needs only to look at the past.”

Comments