Remember My Lai? That was the incident on March 16, 1968, when U.S. troops commanded by Lt. William Calley and Cpt. Ernest Medina massacred at least 500 unarmed women, children and elderly people in the South Vietnamese hamlet of that name. Many of us were told that My Lai was an aberration, not the result of policy.

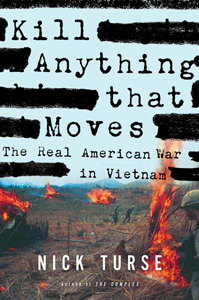

But in his new book “Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War In Vietnam,” Nick Turse aims to sear into our brains the message that the way the United States waged the Vietnam War involved massive war crimes carried out against the civilian population of South Vietnam, and that the My Lai incident was only the tip of the iceberg.

Further, he wants us to understand that the killing, torture and massive destruction wreaked by U.S. forces and their South Vietnamese and South Korean allies did not merely stem from the angry behavior of rough soldiers under the stress of battle, but were the direct and knowing result of policy decisions taken at every level of the military and political structures.

Many readers will recall that we were told that besides fighting the “Viet Cong” (National Liberation Front) and North Vietnamese units, the U.S. war effort involved “winning the hearts and minds” of the people in cities and countryside. But Turse’s book shows that what determined action on the ground had nothing to do with this idealistic-sounding phraseology. More relevant was what Turse calls “the mere-gook rule,” “gook” being the racist term U.S. forces used for any and all Vietnamese people.

This “enabled soldiers to abuse children for amusement; it allowed officers sitting in judgment at courts-martial to let off murderers with little or no punishment; and it paved the way for commanders to willfully ignore rampant abuses by their troops by racking up ‘kills’ to win favor at the Pentagon” (p 50).

And rack up kills is what they did. During the war, some conscientious soldiers noticed a discrepancy between the “body counts” which the command gave out and the number of weapons captured. Very frequently, after an engagement, only a few weapons would be listed as recovered from dead supposed Viet Cong fighters. Turse argues convincingly that in many cases, the “kills” were actually of innocent civilians. Since the body count became all important for career advancement for officers in Vietnam, many did nothing to prevent civilians from being simply murdered and then called in as enemy battle fatalities.

Some overachievers stand out. One was Major Gen. Julian Ewell, who, from February 1968 on, set for his troops in the Mekong Delta an initial goal of killing at least 4,000 “of these little bastards” every month. Ewell constantly pressured his subordinate officers to report higher and higher “body counts.” In December 1969, under the rubric of “Operation Speedy Express,” Ewell and his commanders upped the kill ratio even more, and on paper seemed to be having great success in killing far more of the enemy than the casualties his own forces were taking. In reality, says Turse, this seeming triumph was caused by the fact that large numbers of civilians were being massacred.

Turse’s accounts of specific incidents are often very difficult to stomach. In one incident, as U.S. troops shot up some unarmed villagers, they managed to wound a 5-year-old girl. Instead of getting her medical care, one of the soldiers “simplified” the situation by repeatedly clubbing her with the butt of his rifle until she was dead.

Platoon and company commanders gave specific orders for the murder of noncombatants and the destruction of villages, fishing boats, water buffalos, pigs and everything else that the Vietnamese peasants needed to make a living. From the sky rained unbelievable amounts of bombs and napalm. Artillery joined in, and spraying of defoliants such as Agent Orange destroyed the environment over wide regions of the country. As many as 2 million civilians were killed, and some are still dying from chemical exposure.

When soldiers were brought up on charges for killing civilians, as some were, they seldom got more than a light slap on the wrist.

This might seem exaggerated, but Turse based his book on years of meticulous research: Iinterviewing former U.S. soldiers and Marines who witnessed atrocities, going from village to village in Vietnam to interview survivors of the genocidal rampages of Ewell and his ilk, and going through U.S. military and government records whose very existence others writing on this subject were unaware of.

The villains are top U.S. civilian and military leaders including Presidents Johnson and Nixon, Gen. William Westmoreland and other commanders. The role of the media was inglorious; Turse suggests that the My Lai incident motivated them to hide the full scale of the horror rather than expose it further.

The heroes are above all the Vietnamese people, but also a number of courageous U.S. soldiers who did not turn a blind eye to these horrors but tried as hard as they could to expose them and get the perpetrators punished.

To prevent this from ever happening again, everybody should read this book.

Book information:

“Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War In Vietnam”

by Nick Turse

2013, Metropolitan Books, 384 pages, $30.00

MOST POPULAR TODAY

Zionist organizations leading campaign to stop ceasefire resolutions in D.C. area

High Court essentially bans demonstrations, freedom of assembly in Deep South

Afghanistan’s socialist years: The promising future killed off by U.S. imperialism

Communist Karol Cariola elected president of Chile’s legislature

Comments