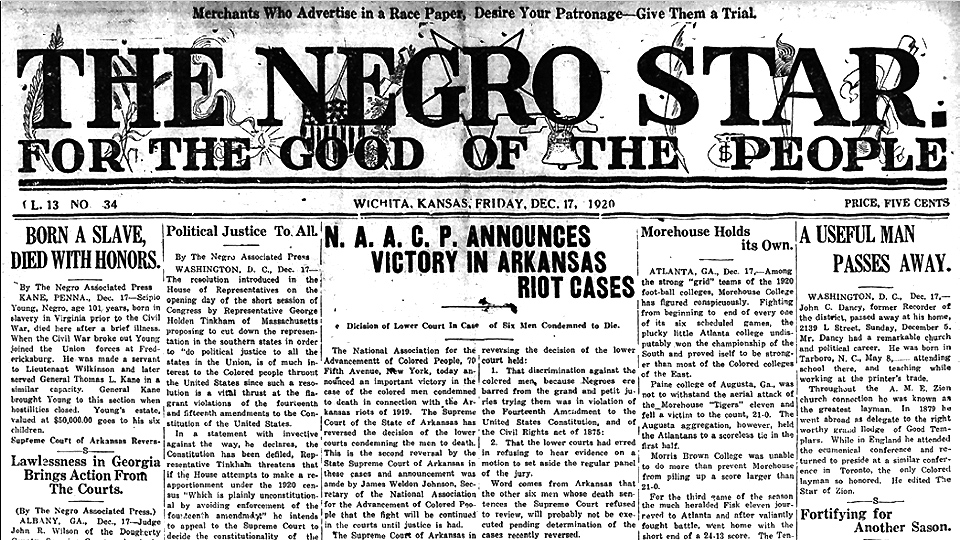

Analyzing the role of media in the collecting and disseminating of information is hardly a new intellectual endeavor. Volumes have been written on the subject and its evolution. As a resource, media—especially the print press in the 20th century—has provided historians with a nearly endless array of subjects, while also ensuring a unique glimpse into key events and people reflected in the partial snapshots and context of the times.

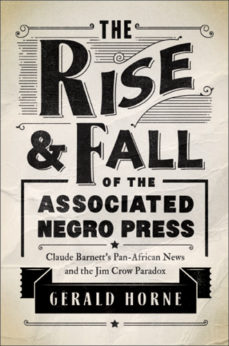

Gerald Horne, arguably one of the most prolific and important historians working today, can now add to his impressive list of subjects an analysis of the Black press, as The Rise & Fall of The Associated Negro Press: Claude Barnett’s Pan-African News and the Jim Crow Paradox deals specifically with one of the key forces in this industry—the ANP—and the personalities surrounding it.

Published by the University of Illinois Press, The Rise & Fall of The Associated Negro Press is part biography, part history, and part political science.

Though relatively short, the book provides perspective into the impact of the Black press during the era of the Jim Crow laws and their demise, as well as Claude Barnett’s role as an unofficial ambassador of sorts to decolonizing nations. Additionally, Horne looks at Barnett as a moderate civil rights activist who juggled conflicting interests; he kept conservative company domestically—and sought adulation from those within the higher echelons of political power—while building relationships with Black Liberation leaders internationally.

Horne also places Barnett within the evolving Cold War political context of the times. In short, Barnett welcomed left and communist support when expedient, but jettisoned it as the political winds shifted.

Ultimately, Barnett proved to be an important African-American entrepreneur as well as an opportunist, a man who supported workers’ rights when it was profitable—which wasn’t often.

As Horne notes, “Barnett was torn when it came to dealing with unions. He was attracted for class and financial reasons to captains of industry…but he could hardly ignore porters and waiters…” who were predominantly African-American and constituted a bulwark of the ANP’s subscription readership.

Additionally, Barnett was “ambivalent—at best—about the rise of unions…,” arguably the single most important pathway for most African Americans out of poverty. For example, when auto workers at a Ford plant in Dearborn, Michigan began to organize, Barnett sided with the auto manufacturer and argued that Ford provided “Negro workmen one of the finest opportunities they have,” a sentiment he was willing to advertise through the ANP news-service—for the right price!—a service that was distributed to nearly every Black owned newspaper in the country.

Interestingly, Barnett’s international coverage was often sympathetic of decolonizing nations, Black Liberation, and the Soviet Union. And he employed a number of Communists, most notably the novelist Richard Wright and Frank Marshall Davis, future mentor to a young Barack Obama.

However, while Barnett was able to “smoothly” navigate “a rutty road, able to satisfy Communists and Republicans alike,” by the late 1940’s “his options were narrowing.” He had a difficult choice: Curry favor with the high-heeled power brokers and reap huge financial reward, or throw his lot in with the majority of African Americans and their class. Barnett chose the former, though it did not save him from the then-ascendant ‘Red Scare,’ as the FBI followed and reported on the erstwhile Republican, his “reputation of being a conservative” notwithstanding.

However, as Horne argues, Barnett’s success was precarious. ANP reporters were underpaid and overworked and quickly moved onto greener pastures as the walls of Jim Crow—within society at-large and within the media industry—came tumbling down. Herein lies the paradox: As Jim Crow stumbled toward its demise, and as more and more African Americans were welcomed into the media mainstream, Barnett not only lost his competitive advantage and target market, but also his staff.

African-American reporters found work elsewhere, while mainstream newspapers began to provide coverage of issues important to people of color, a market once thought nearly exclusive to Barnett’s ANP.

The Rise & Fall of The Associated Negro Press is an immersive read, a welcome contribution to our understanding of the evolving relationship between African Americans and the media during Jim Crow and its demise. It also illuminates the dynamics between Black entrepreneurs and civil rights, and the role international pressure can bring to bear on behalf of Black Liberation.

For anyone interested in these subjects, Horne’s latest work comes highly recommended.

For anyone interested in these subjects, Horne’s latest work comes highly recommended.

The Rise & Fall of The Associated Negro Press: Claude Barnett’s Pan-African News and the Jim Crow Paradox

By Gerald Horne, University of Illinois Press, 2017, 272 pages

Paperback edition $24.95, also available in hardcover and Kindle editions

MOST POPULAR TODAY

High Court essentially bans demonstrations, freedom of assembly in Deep South

U.S. imperialism’s ‘ironclad’ support for Israel increases fascist danger at home

UN warns that Israel is still blocking humanitarian aid to Gaza

Resource wars rage in eastern Congo, but U.S. capitalism only sees investment opportunity

Comments