Unemployment is low, profits are high, but wages remain stubbornly flat. Could the decline of organized labor be to blame?

In October, as unemployment fell under the hallowed five percent notch in California, wages went nowhere. Nationally, the average hourly wage actually fell by a penny. This predicament—a tight employment market and stagnant low wages—completely contradicts conventional American economics.

A recent survey from Bankrate.com underscores the plight of today’s workers. In the last year, the survey found, only 38 percent of employees received any wage increases, and most of those came because of new job responsibilities or promotions. Overall wage growth amounted to a measly 2.5 percent! This as corporate profits are at historically high levels. This, the news media reports, has economists “puzzled.”

Social commentators say it more bluntly. In a new book excerpted in last month’s Harper’s magazine, Malcolm Harris wrote:

“This generation is the most educated in American history, yet its members are worse off economically than their parents, grandparents and even great-grandparents…. As it turns out, just because you can produce an unprecedented amount of value doesn’t necessarily mean you can feed yourself under twenty-first-century American capitalism.”

What’s going on here is an old story. Over a century ago, Chester Rowell, a Fresno journalist and civic leader, characterized the prevailing attitude among employers in a 1903 editorial:

“The main thing about labor supply is to muleize it…. The supreme qualities of the laborer are that he shall work cheap and hard, eat little and drink nothing, belong to no union, have no ambitions and present no human problems…some sort of human mule….”

While it’s rare to hear workers described as mules these days, many feel they’re being treated that way. Capital & Main has reported on such complaints at Tesla—the car of the future but, apparently, manufactured in a workplace from the past.

What makes that workplace difficult for individual employees? Rowell named it more than a century ago: No union.

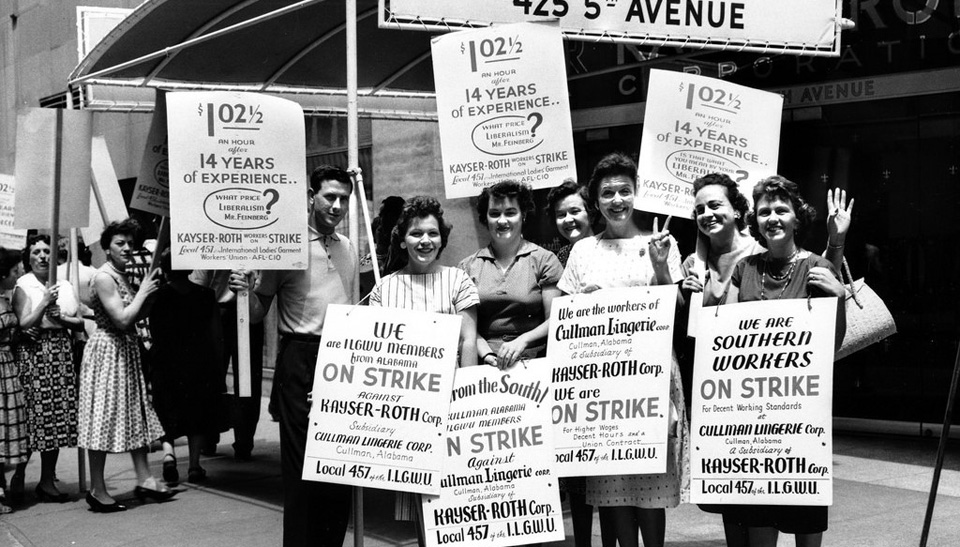

The only thing that stands between an individual worker and a giant company is an association of employees. In this country, that usually means a union. And yes, unions do get big, are often clumsy, and, like all large institutions, can get lazy. But no other entity stands between managers and owners singularly focused on higher profits like an active union advocating for employee rights. No one else pushes not just for wages, but also working conditions, safety, pensions, health care, vacations, and a voice for grievances. Taken all together, those benefits mitigate the all-powerful employer’s prerogatives.

Union membership levels also lift the pay of non-union employees. Where an industry has a strong union presence, wages for non-union workers in that industry rise. Where unions are strong in a region, wages increase. Families can actually feed themselves.

Organized labor carries clout in the larger public arena as well. Unions lobby legislators and provide a counter-narrative to big employers. They can raise a powerful voice for low-wage workers, as in the campaign that led cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, and eventually California as a whole to establish a “path to $15”—the effort to incrementally raise the minimum wage. And unions provide a substantial source of campaign support for elected officials who can then write laws protecting workers as well as consumers. Union presence balances corporate power.

That’s why corporations and most of their super-rich investors hate unions. It’s why they have fought for decades to demonize and destroy them. It’s why they put their money behind candidates for public office who will dismantle the laws that enable unions to represent working people. It’s why a case like Janus v. AFSCME has made it to the Supreme Court. It’s why people’s wages haven’t budged in decades. It’s why many working families still struggle to put food on the table.

Reprinted by courtesy of the author and Capital & Main.

Comments