MEMPHIS—In the midst of a multi-day commemoration of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s life and legacy here in the city where he was assassinated 50 years ago, the Poor People’s Campaign held a press conference today announcing the pending release of a major report, The Souls of Poor Folk, and the countdown to the launch of the organization’s 40 days of civil disobedience campaign.

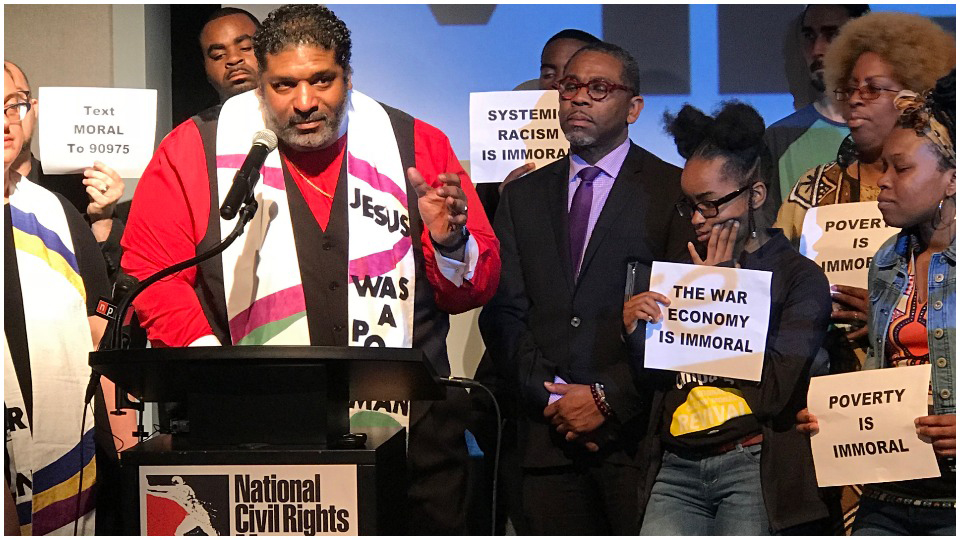

Speaking at the National Civil Rights Museum, campaign co-chairs Rev. Dr. William Barber and Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis outlined the major themes of the upcoming campaign aimed at “challenging the evils of systemic racism, poverty, the war economy, ecological devastation, and the nation’s distorted morality.”

Barber announced that in one week the Poor People’s Campaign will hold a national press briefing to release a one-year study called The Souls of Poor Folk, “auditing America 50 years after the first Poor People’s Campaign.” The study is the result of a partnership with the Institute of Policy Studies and scholars of the Urban Institute.

“Forty days from this week, on May 14, poor and impacted people, along with clergy and political leaders, advocates, and people of all races, colors, creeds, and sexualities will engage in 40 days of non-violent moral fusion direct action,” Barber stated. “This will happen in Washington D.C., and at least 30 other states, focused on Congress and state legislatures to shift the moral narrative in the country—along with voter registration and power building among the poor and dispossessed.”

The current Poor People’s Campaign takes its name and inspiration from the first poor people’s campaign King had planned to launch in 1968, the year he was assassinated. It was to culminate in an occupation in Washington, D.C. demanding better jobs, homes, and education for the nation’s poor. Following King’s murder, the campaign, led by King associate Rev. Ralph Abernathy, did hold a march and six-week occupation of the National Mall that was eventually evicted by police.

Speaking to what he called “five interlocking injustices” that still plague society today, Barber said, “These are issues that are far too often not at the center of our nation’s moral narrative. Those are systemic racism, systemic poverty, ecological devastation, the war economy, and distorted and misguided religious nationalism.”

“We have less voting rights today than we had in 1965 when the Voting Rights Act was first passed,” Barber declared. “Fifty years later, after the first poor people’s campaign, the conditions that inspired the campaign have worsened,” he declared. Barber noted that the number of Americans living below the official poverty line today is in fact sixty percent higher than in 1968—rising from just under 25 million to more than 43 million.

“We aren’t doing this just because Trump got elected, although that exacerbates the problem,” Barber explained. “The reality is, since the first poor people’s campaign, the problems of poverty, war, and systemic racism have taken a side seat. We are raising up from the bottom to save the soul of this nation… It’s time now,” he said.

Barber also admonished those reporters present not to box the Poor People’s Campaign into pre-conceived political categories. “This campaign is non-partisan. Please media, do not call us ‘the Left’. That’s language from the seventeenth century. We are not right or left. We are standing in the moral center for justice,” he declared. Reflecting again on the King legacy, Barber explained, “We are picking up the baton and carrying it the next mile.”

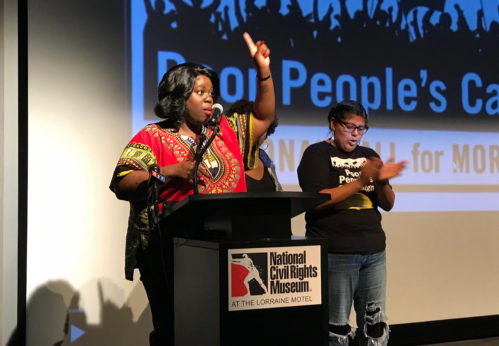

Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis took the mic to say that the campaign was reaching “across all the lines that divide us” in order to break through and bring attention to the dysfunctions of our current political and economic system. She went further, saying, “We’re going to start a moral movement that is based in our local communities…. We take seriously Dr. King’s words at the end of the march on Washington.”

King’s advice, she said, was “to go back. Go back to Alabama. Go back to Mississippi, to go back to the cities and towns and build from the bottom up. Folks will see that a movement is afoot. We’re here in Memphis to say we need to reignite the poor people’s campaign. We’re here to announce that a new and unsettling force is taking over the nation.”

Addressing the media directly again, Barber explained that there is a need to evolve the terms that are used to report on the plight of the poor and the working class. He argued that the terms “attention violence” and “public policy violence” need to be used and defined.

“Attention violence is what happens when we have political discourse but never mention the poor. Coretta Scott King said that violence is not just what happened to her husband [when he was shot], but when people are denied healthcare and other necessities to live.”

Speaking about public policy violence, Barber said that thousands are dying due to lack of health care, “not because God called them home, but because of bad policies made by public officials.” Although this is not usually seen or reported on as violence, he argued it should be considered violence committed against the poor and the working class. “We are a non-violent movement bringing attention to the various forms of violence against poor and working people.”

Responding to a reporter’s question on whether the Poor People’s Campaign would, like King had planned in the original campaign, aim for a march on Washington, Barber took the opportunity to expound on King’s radicalism.

“It’s important that you say in telling the story of Dr. King, that it was Dr. King and 25 other organizations. Because a lot of people, and some civil rights organizations, weren’t with Dr. King [even internally] when he decided to combine the fight against the triple evils of racism, poverty, and militarism [post-1967]. That is an important piece. Those 25 that joined with him all those years ago have told us that they’ve been waiting [for this]. For a fusion movement. Dr. King wasn’t just trying to lead a march in 1968. He had every intention of leading an occupation in Washington.”

Speaking about the future of the movement and its relation to the King legacy, Barber said, “We want to first go after the narrative so that we are not just talking about these issues on a fiftieth anniversary…. You can’t take Dr. King and turn a lion into a small cat. As a famous saying goes, ‘Woe unto those who love the tombs of the prophets because the tombs can not trouble us.’ We’re not here [today] to just talk about Dr. King’s assassination, but to honor him, [and those leaders who challenged society like he did], by taking the baton, and carrying on his legacy with our work.”

For more info about the Poor People’s Campaign, visit here.

MOST POPULAR TODAY

High Court essentially bans demonstrations, freedom of assembly in Deep South

UN warns that Israel is still blocking humanitarian aid to Gaza

Resource wars rage in eastern Congo, but U.S. capitalism only sees investment opportunity

U.S. imperialism’s ‘ironclad’ support for Israel increases fascist danger at home

Comments