In Dorothy Healey’s memoir, California Red: A Life in the American Communist Party, she reflected on the 1949 Foley Square Trial in which the federal government targeted the leadership of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) under the Smith Act for supposedly advocating the violent overthrow of the government. Healey wrote:

“One of the most depressing aspects of the trial was that unlike the great political cases of the 20s and 30s, like that of Sacco and Vanzetti or of the Scottsboro Boys, or even the hearings of the Hollywood Ten in 1947, there was almost no public outcry. Liberals were divided, demoralized, or worse yet, in some instances enlisting on the side of our prosecutors… [A]s the 50s began, it seemed to us we were on our own.”

The trial, Dennis et al v. United States, represented an escalation of the U.S. government’s tactical war against the CPUSA by harassing, hunting down, deporting, indicting, and locking up the leadership of a domestic political party. The government did not stop at Foley Square; as Healey notes, subpoenas soon followed to sweep up her and other local party leaders. Many, like Healey herself, went underground. Between 1949 and 1957, over 144 Communist Party members were ultimately indicted, sentenced to long prison terms, and fined $10,000 each (equivalent to over $100,000 in today’s money).

Why the story of the U.S. government attempting to liquidate a legal political party while at the same time it was lecturing other countries about human rights, free elections, and political prisoners is not better known is probably because it undermines the U.S. myth that the country occupies the moral ground globally. Obscuring the complicity of the two major parties in perpetuating the Red Scare prosecutions feeds the image of alternating left and right wing government at the head of this empire.

The roots of the Dennis prosecutions go at least as far back as the early 1920s when the Russian Revolution sent shockwaves rolling over Western elites, especially in the U.S. The government campaign against radicals, which first made a splash with the imprisonment of Socialist Party leader Eugene Debs during World War I, was the forerunner of the infamous COINTELPRO of the 1960s and ‘70s, when even assassination was deployed against Black and First Nations activists.

Long before the current occupant of the White House, his kindred spirits, like J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI, were already vowing to “take their country back.”

At any rate, the Red Scare, the anti-communist witch hunts, and the Foley Square Trial were to have the desired result of gutting CPUSA membership and bankrupting the party. In states like Hawaii, where the party had been vibrant, the federal trial in Honolulu all but erased any signs it had ever existed.

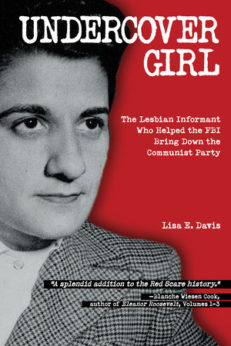

All that pre-history brings us to a new book from author Lisa Davis which adds even more disturbing information about the nature of that infamous trial from one of its unknown provocateurs. The title, Undercover Girl: The Lesbian Informant who Helped the FBI Bring Down the Communist Party, sums up the crux of the book better than Cliff’s Notes. Informant. FBI. Communist Party. Lesbian.

One of the reasons for Healey’s lament that there was no one around to support the party as the government escalated its political war against it can be traced to the young, white female photographer in New York whose perjury Davis, a professor for the City University of New York, chronicles.

Angela Calomiris, previously unknown as a figure in the drama of the Cold War, played everyone, and she seems to have done so right up to the end. J Edgar Hoover and his G-men who paid her, Eleanor Roosevelt who tried to make a celebrity of her, the WPA Photo League that hired her, the New York Police Department, and at least a part of the Communist Party.

Due to sustained government attacks, the CPUSA had by the end of the 1940s begun to shift its internal tactics—to its own detriment.

How Calomiris caused such harm to the party is vividly detailed in Davis’ book, and it is not so much a testament to Calomiris herself—she is neither especially brilliant nor particularly anti-communist. She’s more Scarlett O’Hara than Mata Hari. Her own turgid memoir, Red Masquerade, sensationalizing her life “undercover,” was at best a flash in the pan, unmemorable, and not a door to even a second-rate writing career.

Calomiris’ ambition to make a buck at all costs and the FBI’s paranoia that Western capitalism was vulnerable to communist ideology made their marriage ideal. But their union spawned some disastrous progeny for a radical party which had laid the seeds and supplied the fertilizer for the industrial trade union and Black civil rights movements. The seismic rupture resulting from the government’s witch hunt would have horrible consequences for both movements in the long-term.

Combine the CPUSA’s own growing paranoia about the fiber of lesbian and gay communists in its ranks and you have the perfect storm for what Healey describes as essentially a campaign of self-sabotage as the party looked within for signs of danger.

The indictment in the Foley Square Trial read that the CPUSA “conspired…to teach and advocate the overthrow of the Government of the United States by force and violence.”

In the tradition of the Dred Scott Decision, the sanctioning of Jim Crow in the Plessy case, and the legitimization of the internment of Japanese and Japanese-Americans in WWII, the United States Supreme Court affirmed the Communist Party had no First Amendment rights.

Davis has unpacked the elements of this Foley Square case for her audience, who should be alarmed that the state—through both public institutions and quasi-secret ones—conspired to subvert a legal political movement.

She has written this book not for the scholarly journals laden with academic jargon, but rather for a mass audience who should have learned of this domestic terrorism in high school if we had a real breadth of political discussion in this country.

Put another way, Undercover Girl reads like a mass market piece of lesbian suspense fiction overlaying solid research, and this makes the book a page-turner. What else could you expect from the author of Under The Mink, a novel about lesbian and gay Greenwich Village subculture, pre-Stonewall? Davis’ work has also appeared in the journal Queer View Mirror 2.

The story and its characters are laden with duplicity. “Red Masquerade” would have been an appropriate title for the cast of characters. It would have illuminated the nature of who they presented themselves to be versus who they really were.

Fittingly, Calomiris’ own memoir is a character in itself in the book—and the biggest con job of all. Apparently, it risked ruining the Feds’ case against the CPUSA by openly contradicting her own perjury with more lies, and created new lies on top of all that. This worried her handlers, but not enough to stop paying her and collecting more lies.

Calomiris was on the make for a corrupt federal police agency that asked few questions. She duped the Feds, and the Feds duped her (she wanted a full-time job). They both duped the Communist Party and the Courts, and the presiding judge allowed the jury to be duped by openly defending Calomiris on the witness stand and silencing a defense witness for explaining the goals of the party.

Ironically, Calomiris was spared further collateral damage when the CPUSA turned in on itself, making the decision to officially expel lesbians and gays from its ranks on security grounds.

The party leadership, according to Davis, was split just enough to give Calomiris, the sexually ambiguous mole, a pass. Calomiris, only suspected of being a lesbian, remained on the inside where she was able to feed streams of misinformation and badly-woven lies up the chain of the secret police right to Hoover’s desk. For this, she was paid and paid regularly, a fact which she was allowed to hide from the jury (with help from the judge).

Many other party members weren’t so lucky. Healey recounts in her memoir that as Communist Party chair in California, she was given the task of expelling Harry Hay, an out gay man, who had been a member and organizer of the party for over 17 year and been put in charge of Marxist education locally.

She describes this decision, with the absolution that only memoir affords. The expulsion, and others like it, was “a self-inflicted wound” to the party, according to Healey.

Acknowledging this indiscriminate purge of lesbian and gay Communists, however, does not come with a shred of hindsight or reflection as to why the Foley Square trial defendants found themselves feeling they “were on our own.”

Both Davis and Healey note in detail Hay’s subsequent militant activism as a leader in radical gay liberation movements. He went on to found the nation’s first gay rights organization, the Mattachine Society (which he would also be forced to leave due to anti-communist paranoia) and the Radical Faeries.

Further irony is to be found in the fact that the anti-gay purge within the CP was being carried out at the same time the Feds were expelling lesbians and gays from federal service and while the UAW and CIO were expelling communists.

Not wanting to miss an opportunity to exploit as many prejudices as she could, Calomiris even used the party’s work with the Black community to fan the flames of J. Edgar’s witch hunt.

When CP National Board member Henry Winston, a longtime Black party leader, was on the witness stand testifying about his reasons for joining the Communist Party, it was the presiding judge who, wanting to create a different narrative, kept cutting him off.

Calomiris, who seemed to take a Bull Conner perspective on the “white” CP stirring up trouble among Blacks, also referenced “alleged lynchings,” as if these things were urban myths and Blacks were just being stirred up. In Red Masquerade, she went even further by employing old antebellum images of Black (Communists) threatening the sanctity of white womanhood and racial purity.

Hay’s career trajectory is the inverse of Davis’ central villain.

Calomiris, who had no radical fiber in her being, assimilated nothing from the CP. She seeks to promote herself like any two-bit lawyer for any person willing to pay her and ends up living a comfortable life investing in real estate in the up-and-coming Provincetown market.

Hay ends his life plunged into a manufactured controversy aimed at discrediting his lifetime of activism by those gay assimilationists he viewed as betraying gay liberation.

Calomiris’ hope to be a fulltime FBI agent is rejected.

From Davis’ vantage point, we see a cast of characters playing their assigned roles rather than standing for anything like what Americans are fond of calling “their ideals.” In fact, these characters seem to have no character at all.

We can take note of Healey’s lament that the Communists of the early 1950s felt alone and pledge not to repeat their errors.

Undercover Girl: The Lesbian Informant Who Helped the FBI Bring Down the Communist Party

By Lisa Davis

Imagine Press, 2017

256 pp.; $17.99

Comments