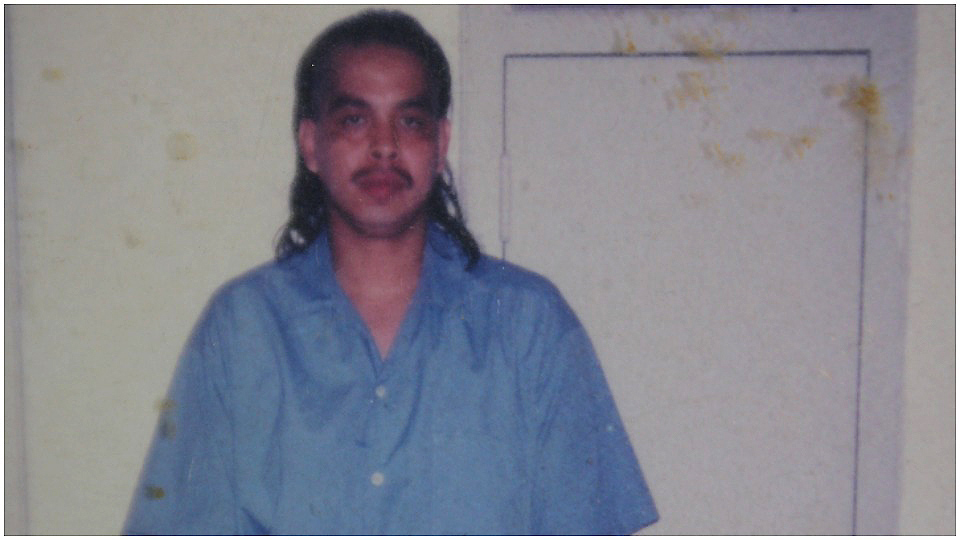

McALESTER, Okla.—“I only want my freedom back,” Robert Mitchell wrote. In an exclusive letter sent to People’s World, Robert finally speaks out from prison. “Again thank you for putting my story out there. I do not want to disrespect the victim’s family,” Robert reiterated as he only desires to be free.

In the letter, he describes being raised by his paternal grandparents, Chester and Lottie Mitchell. He grew up in Little, Oklahoma. Little is a rural, sparsely inhabited community in the northern part of Seminole County. It sits some 16 or 18 miles due south of Prague, Okla., on the Interstate 40 corridor. If you drive along Oklahoma Highway 99-A you see run-down, some abandoned, mobile homes, a few dilapidated barns, and a few nicer homes. Most houses are square Indian homes sitting on the Seminole Nation boundary. The only school is Strother, which has very few students compared to most metropolitan schools.

Robert explains growing up around stomp grounds and learning to lead songs during the ceremonies. For any young Indian boy, the tribal stomp dances and church meetings are the only social outlets. Tribal stomp dances for the Mississippian Mound tribes are an ancient ceremony. A central fire sets in the middle of three willow branch brush arbors. The arbors are sitting areas for boys and men in the West, North and South. The East is open. The fire is lit promptly at sunset and stays lit till sunrise. The men lead the tribal language songs with women keeping time with turtle shell shakers laced around their legs. They dance counter clockwise with 5-10 minute songs all throughout the night. This is the custom Robert grew up with at the Snake Creek stomp grounds.

“I met a Native stomp dance leader, he gave me a stomp dance tape that played clear stomp dance songs. He said, ‘Just play and listen’ and in one year he will expect me to lead my songs at the grounds,” Robert wrote. “After 1 year, I felt ready. All the free time I had, I listen to that tape, even walking in the woods behind my grandmother’s home where I go fishing, or just walking in the woods. I was always listening to that tape.”

Robert describes the Miller family who lived nearby as taking him to stomp dances and church each Friday through Sunday. He would spend the nights with them as they had children near his age as well. This reinforced his knowledge of the language and culture of his Indigenous lineage. “Every year from when I was 10 years of age till 14 years old, I stayed with Alan Miller and his family,” Robert said. He goes on to say that these experiences between May through September are where he learned to respect elders. “What I mostly learned from all the elders is respect and patience. I truly respected all elders. I helped them, listen to them, and learned from them.”

Growing up was harsh on Robert. “My grandma and dad didn’t have much money to buy me good (rich) clothes. I had to do odd jobs, like mowing grass, cleaning yards, selling can good. That was my way of getting good clothes or having spending money,” Robert stated.

The night of September 4, 1992, changed Robert’s life forever. “I was on the phone that night with my girlfriend, Beatrice, discussing where we could be going and what grounds was dancing,” Robert emphatically said. “Her stomp grounds was dancing that weekend and asked if I wanted to stay with her and her mother. I said yes, but would have to ask my grandmother.” He goes on to describe how his grandmother came into his room to say dogs were barking towards the dirt road in front of their house. “I told her I did not see anything and she laid back down. A few minutes later the dogs start to bark again but not just our dogs, but the neighbor’s dogs started barking too,” Robert wrote.

“My grandmother called for me, and when I got to her room, she told me she saw a bright light on back of Ms. McGeehee’s home. She told me to check on her,” Robert said. Robert walked over and knocked on her door, but no answer came. “Her reading light was on but she wasn’t sitting in her chair. I looked into her window but no sign of her. I turned (flash) light on and shined through but nothing.”

“I walked toward back of her home when I noticed items on back porch stairs. I got closer and noticed her back door open, I turned flashlight off and walked in,” Robert described. “I turned to right and in her kitchen, she was laying on floor between table and cabinets. I walked around table toward her head, I asked her she was hurt. All I heard was her gasping for air.” That was when he heard a noise in the backrooms and he quickly exited and returned home.

“When I told my grandmother what I seen she said for me to call her (Ms. McGeehee’s) son. I called her granddaughter but got no answer. So I called her son and I told him what I saw and for him to come ASAP,” Robert said.

The rest of his letter, which you can read here, reiterates what has previously been reported. At no time did the police or Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation follow up on leads given pointing to an intruder and car driving away. Instead, the police and justice system framed and railroaded a 15-year-old Indigenous boy for a murder he is innocent of.

Robert states honestly, “Do I hate the victim’s family? No, I don’t. Do I forgive them? Yes, I do! I hold no hard feelings toward anybody. That’s not how I was raised. I just want my freedom!”

MOST POPULAR TODAY

High Court essentially bans demonstrations, freedom of assembly in Deep South

U.S. imperialism’s ‘ironclad’ support for Israel increases fascist danger at home

Zionist organizations leading campaign to stop ceasefire resolutions in D.C. area

UN warns that Israel is still blocking humanitarian aid to Gaza

Resource wars rage in eastern Congo, but U.S. capitalism only sees investment opportunity

Comments