CULVER CITY, Calif.—At a recent gathering of scholars and academics discussing “Alternative Realities: Utopian Thought in Times of Political Rupture” held at the Wende Museum of the Cold War in Culver City, and at the University of Southern California’s Doheny Memorial Library close to downtown Los Angeles, the air was filled with erudition.

One had to smile with a certain sense of bemused indulgence at some tongue-twisting, mind-bending lecture titles that university folk like to devise. A few examples (of many!) will have to suffice: “Disruptive Technological Development as the Bottleneck Towards Utopia,” “Werner Bräuning’s Rummelplatz and the Utopia of Socialist Bio-Politics,” or “Sensing Dystopia: On the Interaction of Grand Visions and the Senses: A Case Study on Peasant Utopian Ideas in the Soviet Union.”

The content of some of these 20-minute presentations, often accompanied by slides, included a heady brew of intellectual concepts and a cosmopolitan academic vocabulary drawn from the worlds of social science, literary theory and political discourse. I have never heard the word “liminal” used so many times over the course of two days (April 16-17).

Nevertheless—and I say this as someone who was for a time embedded in that world—these professors and researchers are teaching our students today and imbuing them with fresh ways of looking at our past. I might have wished for some contemporary activists working on “utopian” projects to bring the discussion squarely into the present day. But by dissecting movements and ideas of the past with such concentrated dedication, we may be able, in the first place, to understand the past—which is neither easy nor enjoys the luxury of common consensus—and then point the way toward a more just future in which we avoid some of the most egregious mistakes to which our sorry humanity is prone.

Sadly, we have never lived in a world of “best practices,” and likely never will, although a number of speakers mentioned the Scandinavian model as hopeful.

But the utopian vision is still a viable field of study. As we march forward we just conceivably might learn something from those before us who dreamt and organized for a better world.

The Wende Museum of the Cold War specializes in cultural artifacts from the Soviet Bloc countries, and as such has a European focus. Co-sponsors of the two-day symposium also included the Centre for Contemporary History at Potsdam (ZZF), the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), the German Historical Institute Pacific Regional Office, The Max Kade Institute for Austrian-German-Swiss Studies, and the USC Dornsife Departments of Art History, History, and Slavic Languages and Literature.

Most of the presentations concerned 20th-century European movements, mainly German, and only tangentially touched on Japan, India, and Africa. One session discussed the kibbutz movement in Israel. Women gave 13 of the 19 lectures. The utopian future is female!

Utopian ideas have existed in one form or another almost since the beginning of recorded history. One can go back, in the Western tradition at least, to the prophetic writings of Isaiah and Amos to find depictions of a just and peaceful world governed by a wise, noble and compassionate king. England’s Levelers and Diggers sought to make human beings equal in social status, and it was the homeland of Sir Thomas More (1478–1535), whose fictional book Utopia, published in 1516 in Latin and in 1551 in English, depicts an island society and its religious, social and political customs, some of which resemble monastic life. It is not coincidental that utopian aspirations should emerge just as the New World was becoming known: It inspired writers to think that on pure, virgin, “Edenic” continents an ideal society could be constructed successfully.

Later expressions of utopian thought include the Enlightenment, socialism, communism, the “workers’ paradise,” back-to-the-land agrarianism, the Christian “beloved community” of Liberation Theology and other movements.

Space permits me to discuss only four of the presentations over the two-day event. (I did not attend the final Panel VI, “The End of Utopia?”)

“Community of the people” as the way forward?

Robert-Jan Adriaansen of Erasmus University in Rotterdam spoke in the opening Panel I (“Utopian Thinkers”) on “Beyond Historicism: Utopian Thought in the Conservative Revolution.” It is a mistake, of course, to imagine that all utopian thinkers are on the left. Some on the right also entertain futuristic visions of their perfect society. In fact, the rise of the radical religious right in the United States exhibits characteristics of such millenarian thinking once we “re”-establish a God-fearing Christian American theocracy.

Adriaansen focused on German writers of the 1920s, such as Stefan George, Oswald Spengler, Ernst Jünger, Carl Schmitt, Hans Blüher and Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, who rejected modernity and rationalism. They imagined a “Third Way” forward beyond monarchism and democracy, beyond collectivism or individualism, that would find its synthesis in some form of New Order, a Reich, or Volksgemeinschaft (a “community of the people”). Such a regime would not derive from a higher order but represent a kind of non-theoretical, intuitive “self-redemption.” Already readers will be thinking to themselves, “Aha, so these are the precursors to national socialism.” And they may be correct to an extent, but it would be overly “cause and effect” to link the tone of such longing in the 1920s for a new organization of the human project to the literal political and economic fascism that emerged full-blown upon the election of Adolf Hitler in 1933.

Training African students to be socialist leaders

Panel II speakers addressed aspects of “State-Sponsored Utopia.” Sara Pugach of California State University, Los Angeles, presented her work on “Pan-Africanism, African Socialism, and Marxism-Leninism: African Students and Challenges to East German Ideological Authority in the 1960s.” Her research covered the quarter-century 1949-1974. Apart from the universities which came back to life after World War II, new academies of learning quickly emerged in the new German Democratic Republic (GDR), sponsored by the union movement and by the Free German Youth (FDJ), to educate young students in the theory and practice of Marxism-Leninism. As part of the socialist desire to attract students from African and other underdeveloped nations to its side in the Cold War, the GDR extended invitations to promising young Africans to enroll in courses of study in various cities. Armed with not only ideological tools, but with technical and professional skills, such students would return to their homelands and form the nucleus of the socialist, anti-colonial, pro-independence movements.

Once the students arrived they took a six-month acculturation course in German so that they could be taught. But the plan did always go smoothly. For one thing, students occasionally found themselves subject to lingering racist attitudes—being assigned to different courses according to their supposedly lower level of preparedness, especially when measured against other foreigners from Latin America, Asia or the Arab countries. And not all were so highly motivated to serve their national struggle: Some were interested more in personal material advancement. Others from Africa were never really clear on the difference between East and West Germany, as both were so much more modern and industrialized than their home countries, and didn’t know where they were going until the last minute. And many Africans could not accept “class struggle” as relevant to their home circumstances: They imagined pre-colonial (and post-colonial) African society as already classless.

Not all students conformed to the image the GDR leadership projected and expected of them. Some were pan-Africanists, or Black nationalists, or later sided with China over the USSR, openly challenging their teachers. The GDR secret police rooted out such non-conformists and sent them home. These students found that the GDR fell short of a socialist workers’ paradise.

Perhaps because of her time frame, Pugach did not get into the later support, including military, that the GDR and other Soviet-Bloc countries gave to the freedom movement in various African countries. Personally I found her paper informed and factual, but one-sided, for there certainly must have been “success stories” too. I would have liked to hear some of those.

To reclaim the illusion of local control

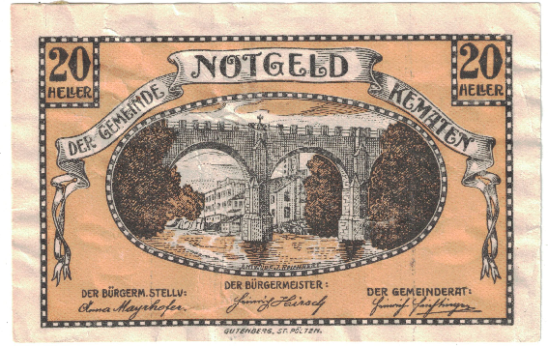

“Landed Utopias” was Panel III, and on that one Eric Sullivan Maynes, a staff researcher for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, spoke on “Currency and Craft: The Creation of Community in Inflation-Era Thuringia.” In the years immediately following the First World War, 1918-1923, the German economy was recovering with great difficulty. Famous are the images of wheelbarrows piled with banknotes that consumers brought to market to purchase a loaf of bread. But in various places, people adapted to these radical situations by printing their own “Notgeld”—money in time of necessity. These alternative currencies issued in different denominations represented a rejection of national financial problems in a regional attempt to claw back some illusion of local control.

In some cases the notes were attractively designed with imagery of local towns or folklore, and were meant to be sold more as collector’s items than as currency. In the central German state of Thuringia, where the cities of Eisenach, Weimar, Erfurt, Jena, Gera and Gotha are located, a local folk hero named Friedrich Muck-Lamberty (1891-1984) launched a series of Notgeld notes that supported a “New Flock” of adherents to his communal “free love” endeavors. These projects would include a workshop for handmade furniture and household items that promoted self-sufficiency and the rejection of materialism. Some towns issued Notgeld that specifically advertised local manufacturing.

Maynes tied this history of non-state currencies to certain local issues in places like the Berkshire Mountains of Western Massachusetts, where today Berkshares are commonly traded and accepted in local stores. Such local currencies also exist in areas of the UK, such as Brixton and Bristol, in Ithaca, N.Y., and elsewhere. In some cases the note is traded for time, for example, one-eighth of an hour of work. One can only wonder if in a “time of political rupture,” as the title of the symposium indicates, our own time is such a moment, when transactions will take place more and more outside the taxable, bankable system. For example, the marijuana business which, because of lingering federal illegality, languors unmonitored at the edges of the legitimate economy.

“Human nature” and the collective

Finally, Anna Krylova from Duke University spoke on “The End of Utopia: Socialist Imaginaries in the Soviet Century,” on Panel V, “Utopian Continuities and Discontinuities.” Born and raised in the Soviet Union, Krylova has studied this “experiment in socialist modernity” and published extensively on it. Within the overall paradigms of capitalism and socialism she finds it important to identity within each type of society those adjustments, growth nodes and changes that take place still assuming those fundamental tenets. She points to a systemic break between the “Bolshevik” and the “Soviet” vision of the new society, with differing patterns of social relations. Yet, there is always a pause during these cultural breaks that occurs before a new vocabulary emerges.

In the Bolshevik era the word “Soviet” referred to political organization, governance and administration—the word itself, of course, deriving from the workers’ councils earlier in the 20th century. But there was not yet a Soviet people. There were proletarians of one kind or another, grounded in the theoretical Marxist political economy. Within the proletarian collective the individual finds personal identity. The idea that a person is born with an individual identity was considered a bourgeois concept. The ideal was the worker-engineer, the proletarian who finds their identity in and from the collective.

By the late 1920s and the early 1930s the word “Soviet” had come to describe anything, encompassing everyone, whether proletarian or not, such as professionals, functionaries and university graduates. New class categories were introduced, such as “employees.” The “Soviet proletariat” cannot be equated with the pre-revolutionary proletariat. By now, no single class represented the ideal type to be imitated by all, a logical result of widespread industrialization, specialization and modernization.

The concept of “human nature” starts being developed, the idea that each individual has their own talents and inclinations. Teenagers’ autobiographies in the 1930s began pointing to the recognition of the need to follow their own “natural” gifts. Now, instead of rising out of the collective, a person would combine their own interests with the larger social interest. A Journal of Pedagogy article in 1937 told teachers to discover the individuality of each student and to nurture it. “That thinking would last to the end,” said Krylova. “This is how I was educated.”

She observed, mordantly, that this transition of social philosophy took place just as the Great Purges of the late 1930s physically liquidated almost every one of the former Bolshevik leaders.

If the romance of the proletariat was over, it was not erased. It survived, of course, in the expansive package of social benefits accorded to Soviet citizens. But Krylova pointed out that already in her day at high school and university, students’ actual experience with proletarians was rare. When they were taken on the odd excursion to a factory or mine, they found it a strange world and wondered what they were doing there and why. Perhaps already a new pause between epochs had arrived, without the vocabulary to identify the stage of history being born.

Maybe that’s why academics love this elusive word “liminal”— at the edge, at the cusp, at the threshold.

Comments