When I have occasion to talk to students about Marxist thought and what a socialist society developed according to Marxist principles might look like, they typically express worry about, even hostility to, what they believe such a society would mean for the individual.

Like a tightening stranglehold on our social imaginations, the myth abides that a socialist society founded on egalitarianism somehow produces a drab and moribund world characterized by homogeneity and repressive conformity.

The drab myths of socialism

Their minds conjure a dim world devoid of fashion and creativity where citizens wear the same gray clothes, eat the same bland food rations, and are encouraged (if not ordered) to think the same thoughts and pledge allegiance to rigid belief systems that outlaw disagreement or divergence.

In short, the myth perpetrated against socialism, largely a product of the deeply-rooted anti-communism in American culture, is that it is hostile to and repressive of the individual in every possible way – to individual thought, expression, choice, freedom, and creativity. Sound familiar? I believe this is a fair representation of how many in the United States imagine a socialist society.

The commitment to this myth is a damaging one, and not just because it is so wildly inaccurate. It shows up in our social relationships, appears in public policy, and curtails our understanding of ourselves and our potential. It prevents us from achieving the highest happiness and fulfillment we could achieve as individuals and as a society.

Indeed, Marx and Engels famously penned the phrase, “The free and full development of each is the precondition for the free and full development of all.” Whether or not you are fans of these thinkers, you have to admit, don’t you, that they succeeded in formulating a fundamental truth? It’s hard to challenge the idea that the highest functioning and most productive and creative society will be the one that develops the talents and abilities of each individual to their fullest potential and avails itself of them.

Now, certainly, the question arises as to which kind of socio-economic organization provides the most fertile soil for individual development. It is a dominant belief in American history and society that capitalism creates the best context for individual achievement. It’s not unreasonable to point to, as critics do, the series of repressive regimes like Stalin’s USSR, Maoist China, or today’s North Korea and conclude that Marxist societies are unworkable, undesirable, and hostile to individual freedom and development.

Regardless of their official ideologies, those societies left a lot to be desired from a Marxist standpoint. I would say the essence of the philosophy that undergirds socialism is the interdependence of individual and collective development that Marx and Engels talked about. It is an idea missing from, and even counter to, capitalist thought and practice. Socialism, not capitalism, I suggest, is the highest form of individualism.

Socialist individualism

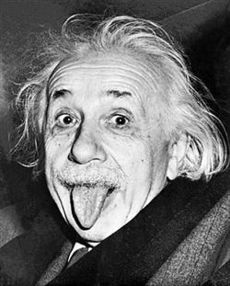

Socialism – or socialist philosophy – provides a fuller and more historical understanding of the individual. This is important if we are to understand and create the historical and social conditions necessary to support the highest cultivation of the individual. To explain this, let me recruit Einstein for a rendering of what I take to be a socialist understanding of the individual.

What is crucial in this philosophy is that it understands the individual not isolated from social relationships but as embedded in them, recognizing the way we actually live historically. As Einstein explains in his 1949 essay “Why Socialism?“:

“The abstract concept ‘society’ means to the individual human being the sum total of his direct and indirect relations to his contemporaries and to all the people of earlier generations. The individual is able to think, feel, strive, and work by himself; but he depends so much upon society – in his physical, intellectual, and emotional existence – that it is impossible to think of him, or to understand him, outside the framework of society. It is ‘society’ which provides man with food, clothing, a home, the tools of work, language, the forms of thought, and most of the content of thought; his life is made possible through the labor and the accomplishments of the many millions past and present who are all hidden behind the small word ‘society.'”

What we need most to take from Einstein is the understanding, counter to typical renderings of American individualist ideology, that individuals depend very much on others to help them meet their needs so they can realize their talents and abilities and make their fullest contribution to the world.

Recognizing this dependence, or this condition of radical and inevitable interdependence, is not a denial of individualism. Rather, Einstein invites us to understand our individual identities in richer and fuller ways by seeing that we realize ourselves most fully in a social and collective context – and necessarily so, because we need the fruits of other people’s labor to meet our basic needs and to make it possible for us to develop our special talents. If we had to spend our time doing all the work to satisfy our basic needs, we would be exhausted and unable to develop our creative abilities and offer our best service and contribution to the world.

This view of the individual, which rests in a recognition of our interdependence with others, is really quite different from and I believe superior to, in terms of its accuracy, dominant conceptions of individualism in American culture. In our current culture, we tend to honor the “self-made” person who has made her own fortune and achieved success through her own hard work. Yet this successful person, Einstein’s writing suggests, likely doesn’t do everything herself but is quite likely dependent on others to have personal needs met.

We tend as a culture to mistake “an ability to buy” for the reality of “having done.” One might amass a fortune and be able to buy anything, but that doesn’t mean one isn’t depending on others to produce their food, clothes, roads, stamps, and so on.

Social-ism

Socialism is called what it is because it asks us to recognize the social dimension of our existence; it provides a lens so we can see how much we rely on the work others do for us that makes our lives possible. It can mitigate the tendency in U.S. culture for people to insist their achievements are theirs alone. In short, socialism understands that individuals rely on society, on others with whom they are necessarily in relationship, for the full development of their individuality.

Recognizing this interdependence, however, is no easy task for Americans. It is fraught with psychological and emotional challenges that grow out of the mythical sense of the individual that so powerfully informs American identity and thought. Einstein diagnoses this difficulty Americans have acknowledging the reality of the individual’s imbrication in and reliance on social relationships in a way I’ve never seen anybody else approach, when he writes:

“I have now reached the point where I may indicate briefly what to me constitutes the essence of the crisis of our time. It concerns the relationship of the individual to society. The individual has become more conscious than ever of his dependence upon society. But he does not experience this dependence as a positive asset, as an organic tie, as a protective force, but rather as a threat to his natural rights, or even to his economic existence. Moreover, his position in society is such that the egotistical drives of his make-up are constantly being accentuated, while his social drives, which are by nature weaker, progressively deteriorate. All human beings, whatever their position in society, are suffering from this process of deterioration. Unknowingly prisoners of their own egotism, they feel insecure, lonely, and deprived of the naive, simple, and unsophisticated enjoyment of life. Man can find meaning in life, short and perilous as it is, only through devoting himself to society.”

It is fair to say, I think, that one of the most formidable challenges facing the left, which I don’t believe it has faced or even articulated, is overcoming this psychological and emotional barrier that causes people to view interdependence pejoratively.

Capitalist culture loves to tell us we are competitive beings and can’t achieve our best without competing against one another. Yet if you were to really pay attention in the world, you would notice, I believe, that you spend far more time cooperating, collaborating, and depending on others to get things done, to achieve your goals, to meet your needs, to take care of your kids, and so on, than you do competing with others.

We in America just tend not to focus on that aspect of our lives. We are not taught to see the world that way or accentuate the cooperative dimensions of our existence. Remember how upset a good portion of the country got when Elizabeth Warren made her famous speech reminding the person who built his own business that he didn’t build the roads he uses to transport the goods he makes? And yet she simply said the obvious.

Competitive and collaborative

Without a doubt, we are competitive beings. I love to play sports, do my best, improve, learn, grow, and defeat my opponent. But I am cooperative and collaborative as well. While on the bowling lanes, basketball court, or baseball diamond, of course I want to defeat my opponent. But if I’m thinking clearly, I want others to succeed too.

I want others to succeed in figuring out how to provide clean water for me; how to produce energy so I can warm my home, cook my food, and drive my car; how to keep my computer working; how to figure out new ways of producing more food on the same acreage to feed growing populations.

Capitalist culture tends to pit individuals against each other. If I want my child to get a seat in the best school, I likely have to root against my neighbor’s child. Thus, a competitive society does not necessarily – and often just doesn’t – lead to a culture whose highest value is the free and full development of each. Our culture creates an environment that encourages us not to seek to help people develop themselves fully, but to take from them. As Einstein noted in his essay,

“The economic anarchy of capitalist society as it exists today is, in my opinion, the real source of the evil. We see before us a huge community of producers the members of which are unceasingly striving to deprive each other of the fruits of their collective labor – not by force, but on the whole in faithful compliance with legally established rules.”

A socialist society wouldn’t ask us to be who we are not. It would create a social system that accentuated rather than obscured the cooperative or social dimensions of our beings, leaving us to live out our competitive drives in our places of play. And it would ask us to recognize who we are by coming to terms with the reality of our interdependence and to understand what we gain from the collaborations in our world that allow us to eat, have clothing, receive healthcare, etc.

We can, as a collective, truly achieve our individual potentials if we have social support. In this sense, socialism is, to repeat, the highest form of individualism. Fostering an ethos that encourages us to recognize our interdependence is the key challenge for those working for a socialist society.

If we genuinely recognize and value those whose work enables our lives, would we seek goods and services as cheaply as possible? If we knew that in driving down the wages of workers we were undermining the health and well-being of those on whom we depend, would we do so?

Understanding our individuality in socialist terms is the first step toward re-defining self-interest to truly grasp and appreciate our radical interdependence, giving the meaning of that old value of “self-reliance” a truly new substance.

Tim Libretti teaches in an English Department at a public university in Chicago where he lives with his two sons.

Photo: Wikipedia (CC)

Comments