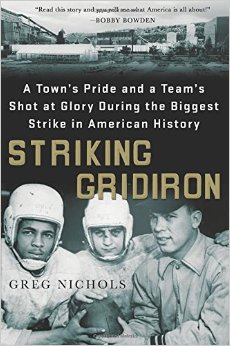

Many of us collect something, and know that feeling of finding that once-in-a-lifetime treasure. Or you’ve had that feeling of glancing down to find a $20 bill, a four leaf clover or something you’d been looking for but had given up. That’s what It felt like when, buying my monthly weight in books at the Half Price store, I happened upon “Striking Gridiron,” (Greg Nichols, 2014, Thomas Dunn Books).

“Striking Gridiron” is based on the 1959 undefeated season of the Braddock High School football Tigers. That was a season in which Braddock broke the previous high school winning record of 56 games that had been set by a Massillon High School team coached by the great Paul Brown, in his first coaching gig two decades earlier, prior to Brown’s founding of the Cleveland Browns.

All that would’ve won me over before opening the book, but that was not nearly all. Braddock is part of the Ohio Valley, which runs from Pittsburgh through Warren/Youngstown and Steubenville, nearly across to Cleveland. It is part of the Pittsburgh area and home, like much of that area, to massive steel mills, in this case the huge Edgar Thompson Works. 1959 was also when the largest United Steelworkers (USW) strike occurred. This was the backdrop to “Striking Gridiron.”

By the end of the 50’s, the “color line,” the term referring to the Jim Crow practice of barring African Americans from teams, had been broken. Pro football was integrated by Paul Brown’s Browns in 1946 and Jackie Robinson broke it in baseball in ’48 with Brooklyn. This created a pressure which resulted in a great many teams, including high school/colleges, “integrating.” This was the case of most Ohio Valley teams as well. “Integrating” at that time meant that they had a single Black player or two, token minorities who were brought in to be part of otherwise all-white teams. However, the Braddock team coached by Chuck Klausing, the central focus of the book, began doing things differently. Klausing strongly believed “fairness and earning your way.” That meant that kids at Braddock had to actually earn their positions, resulting in half the Braddock teams in the ’50’s being African American, an unheard of situation at that time.

Klausing’s defense of his team, the fight against racism, is also a major backdrop to the drama of the ’59 football season.

There was also a very personal item with “Striking Gridiron” that jumped out at me. The front cover shows coach Klausing and some team members, including a young African American player named Ray Henderson. A great many steelworkers knew him later as “Butch” and as a leader in many labor struggles.

I got to know Butch years later, when George Edwards had recruited me into the rank & file reform movement in the USW. That movement had numerous forms, but that particular part of the movement was left-led, organized into the National Steelworkers Rank & File Committee (NSWRFC). NSWRFC put the fight against racism at its core. George Edwards, a leader of the Communist Party as well, was elected as one of the co-chairs. Another co-chair was Juan Chacon, a USWA/community leader from the Southwest who’d starred in the great, once-banned, union film “Salt of the Earth.” Ray ‘Butch’ Henderson was the other NSWRFC co-chair.

None of that is actually part of this book, although at the end, Nichols does speak of Ray becoming a “community leader” and NAACP leader.

NSWRFC, in the 1970s, worked with the USW Black Caucus (which was known as the Ad Hoc Committee of Concerned Steelworkers and was led by Jim Davis of Youngstown) to win a major federal lawsuit (Fairfield Decision-Consent Decree). The consent decree was designed to do a number of things: desegregate hiring/transfer/bidding processes in the steel industry, pay back-pay to African American workers and reinstitute craft training, with minorities and women getting first shots. All this came much later, and none of us who worked with Butch as co-chair knew his celebrated sports background.

I spent my entire adult life with the USW, working at the Lorain mill, for the union, and with steelworkers and their families. I say that to say that the young author, Greg Nichols, did not do any of that, but somehow does manage to “get it”!

Chuck Klausing, the coach and major protagonist of “Striking Gridiron” states, on the book’s inset;

“Greg Nichols couldn’t have written it better if he’d been on the sidelines with us.”

Henderson is one of the team leaders, described as a “block of granite” that “nobody could block or tackle,” and was an offensive end for the Braddock team. Unfortunately, according to Klausing, Butch had “hands of stone,” which in football language is not a compliment. Without giving everything away, this is a problem they had to, and did, overcome, but just in time.

The main rivals of Braddock, where all the kids are sons/daughters of striking steelworkers, is North Braddock, where most of the team is made up of sons of mill managers. I know—-can’t make it up and have it fly, but, of course, the game that will enable Braddock to be undefeated and break the record is against North Braddock. You’ll have to read it, but it IS about their undefeated season!

There are some real struggles, and not just football ones, in this fine read.

Nichols talks of how the corporate steelmill owners underestimated steelworkers. He discusses management’s strategy heading into the ’59 strike, 116 days, and the longest in U.S. history at that time. The companies planned on bankrolling steel, over-ordering to build up huge inventories, which they figured would wear out steelworkers, whose families would get hungry and pressure them to go back to work. As well, this was the ’50s and union militancy had been rolled back. David McDonald, known to many as “Dapper Dave” for his taste for expensive suits, good food and rubbing elbows with bosses, was USW president. Management figured the workers wouldn’t follow McDonald and that McDonald wouldn’t lead. What they didn’t figure on was what the workers did—take over the strike themselves, with mass picketing, huge rallies, pushing city/county officials and the local unions setting up food and rent relief for the strikers.

All this, while the players had to try to help their families, help with the strike and prepare for games that were all-important for those working class communities. The season builds to a climax, running alongside the strike!

Within this context, one of the personal struggles Klausing fought was attempting to get college scholarships for his players. He is extremely frustrated that he can help some players, but was much less successful helping African American players get into college. Butch Henderson is one player that Klausing spoke of particularly working for, but was ultimately unable to help with higher education. It is one of numerous areas where the book takes the fight from their football opponents to institutional racism, maybe doing more to prepare students for life ahead than anyone knew at the time.

I’ve often felt that there are close ties that bound working class culture to the game of football. When the Cleveland Browns were stolen from that city, unions, community groups and others rose up, holding huge demonstrations, marching on the old stadium and demanding use of eminent domain to “take over our Browns!” To this day it has puzzled me that it was easier to get folks to understand, buy into, public ownership of “our Browns” than it was to sell the idea of public takeover of closed mills.

While it still bothers me, since reading “Striking Gridiron,” I think I’ve got a better handle on it.

Our working class culture, especially in steel towns where everyone “is part of” the mill becomes the culture of our people, all-pervasive in those areas. Football, a tough game, especially he early pro game, was born in the Ohio Valley. I remember Lou “The Toe” Groza being interviewed in his hometown of Steubenville. He pointed to a nearby football field, then to a local mine and a steelmill, stating;

“You’ll either make it there, or you’ll have to make there!”

That workers’ culture is formed, in part, by the nature of folks in those towns—-immigrants, East Europeans, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Italians and Russians, and large, older, African American communities. People thrown together in hard, tough situations who can be dead quick if they don’t pay attention, and work together! Folks living where the class struggle isn’t something in books or speeches, it is, whatever it is called there, something those workers take home with them. It is with them always, especially when others look down on them. The disdain, arrogance, of other, wealthier folks who think they’re “better” just pulls everyone together even more. Unity is part of the grit that blows in the window. It had better be, or you just won’t make it!

“Striking Gridiron” is filled with working class culture. Most of the mills are now gone, not because steel isn’t needed but because rich folks wanted to be richer and so they moved those jobs elsewhere. Those proud communities like Braddock have been turned into poverty-stricken ghost towns by unseen wealthy economic royalists. It is tragic!

And, while they’ve hammered us down, “Striking Gridiron” is a book about working folk that won’t be beaten. It is a truly great book about a bunch of truly great people who pulled together and came out on top.

For a while, they were heroes. They were champions.

Comments