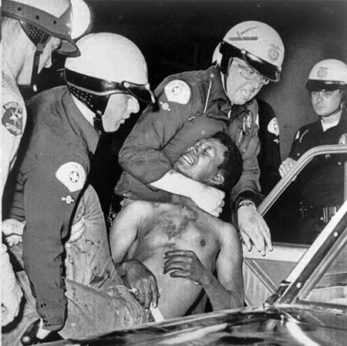

Fifty years ago, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed a commission to investigate civil unrest and “overly aggressive” policing in black communities. The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, better known as the Kerner Commission, found that racism had led to “pervasive discrimination in employment, education and housing.”

The Kerner Commission named after its chair, Governor Otto Kerner, Jr. of Illinois, was an 11-member commission established by Johnson by Executive Order 11365 to investigate the causes of the 1967 civil unrest and rebellion in African-American communities in the United States. It was also tasked and to provide recommendations for the future.

Johnson appointed the commission on July 28, 1967, while civil unrest was still underway in Detroit, Michigan. Mounting unrest since 1965 existed in the African-American and Latino neighborhoods of major U.S. cities, including Los Angeles (Watts uprising of 1965), Chicago (Division Street 1966), and Newark (1967). In his remarks upon signing the order establishing the Commission, Johnson asked for answers to three basic questions: “What happened? Why did it happen? What can be done to prevent it from happening again and again?”

The Commission’s final report was released on February 29, 1968, after seven months of investigation. The report became an instant bestseller, and over two million copies of the 426-page document were sold in the U.S.

The report named “white racism”—leading to “pervasive discrimination in employment, education and housing”—as the culprit, and the report’s authors called for a commitment to “the realization of common opportunities for all within a single [racially undivided] society.” The Kerner Commission report pulled together a comprehensive array of data to assess the specific economic and social inequities confronting African Americans in 1968.

Martin Luther King Jr. pronounced the report a “physician’s warning of approaching death, with a prescription for life.”

The report’s most famous passage warned, “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.”

Its results found that one main cause of urban violence was racism and it called for the creation of new jobs, construction of new housing, and a stop to de facto housing segregation. In order to do so, the report recommended government programs to provide needed services, to hire “more diverse and sensitive police forces” and, most notably, to invest billions in housing programs aimed at breaking up residential segregation.

But according to American University historian Ibram Kendi, “Many of the politicians” and the white constituents they represented “were raging against the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, and against cultural change.” Politicians were particularly incensed by African-American activism because they and their constituents inherited centuries-old attitudes of “blacks as inferior humans.”

The continuing anti-black attitude by whites and politicians is another legacy of 1968, Kendi stated. “To them, Black Power meant black supremacy and not white supremacy, just as in 2018, the Black Lives Matter movement means black supremacy and white opinions don’t count.

“So ‘Law and order’”—the slogan of Nixon and Wallace—“was used to justify brutality, and those fears came to dominate political campaigns over the next five decades,” Kendi explained.

A new report from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) by Janelle Jones, John Schmitt, and Valerie Wilson compares the state of black workers and their families in 1968 with the economic circumstances African Americans face today.

According to the EPI report, today, black workers still make only 82.5 cents on every dollar earned by white workers, African Americans are 2.5 times more likely to be in poverty than whites, and the median white family has almost ten times as much wealth as the median black family.

In 2017 the black unemployment rate was 7.5 percent, up from 6.7 percent in 1968, and still roughly twice the white unemployment rate.

One of the report’s lead authors, EPI’s Valerie Wilson, appeared on C-SPAN to discuss the report’s findings that show—despite significant gains in African American communities—structural racism remains a root cause of the economic inequality experienced by African Americans. Click here to watch Valerie Wilson’s recent appearance on C-SPAN.

The Economic Policy Institute concludes:

“Together, we’re working to lift up all working people, and demanding an economy that works for people of all races, ethnicities and socioeconomic backgrounds.”

Sources include Wikipedia and EPI. Mark Gruenberg and Barbara Russum contributed to this article.

Comments