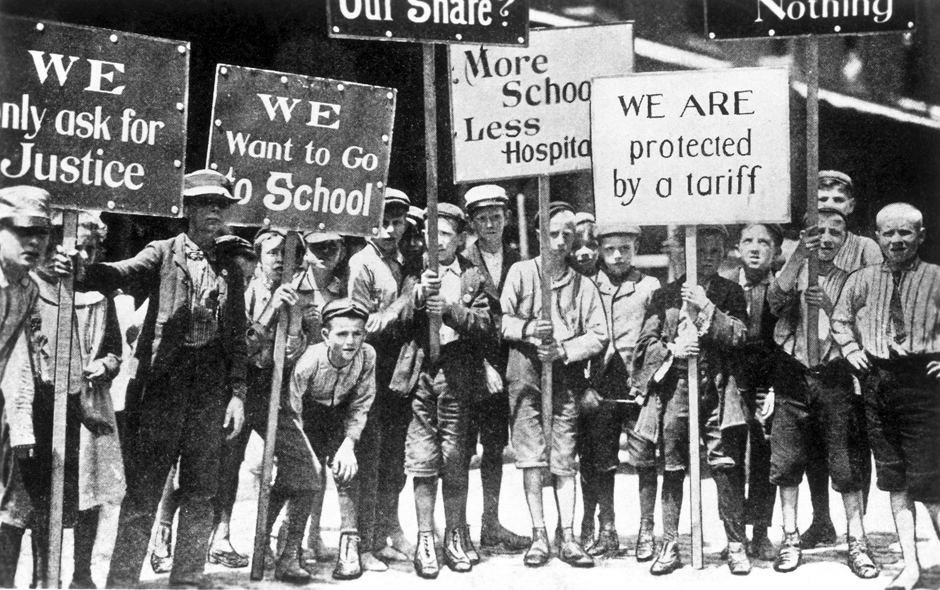

As we celebrate International Workers’ Day, let us not forget those who gave up what should have been the best times of their lives to a rapacious capitalist system—the children. From the late 18th to the early 20th century, child labor was arguably the most exploited of all in the United States. In the mines and textile mills, on farms and in factories, girls and boys as young as five years old would routinely work for twelve or more hours a day six days a week in unsafe conditions, and were paid little, if they were paid at all.

Employers didn’t have to pay subsistence wages to children as they did to adults, which meant that if a child could do a job as competently as an adult, the child would often be the one hired. Being smaller than adults and with little hands, children could work in very tight spaces close to the moving parts of machines. As a result, it was not unusual for a child to lose fingers or a hand—or sometimes their life—in an industrial accident.

Over half of the jobs given to children were considered to be dangerous and and there were no government regulations to protect child workers. It wasn’t until the 1916 Keating-Owen Child Labor Act that restrictions were placed on the number of hours a child could work and the age at which they could be hired.

These dark truths about the lives of many children in the United States have been the subject of an increasing number of fiction and nonfiction books for children. Some of the better ones are discussed here and should be made available to child readers so that they can get a better understanding of what the lives of children their age were like not all that many years ago.

Legendary labor organizer Mary Harris “Mother” Jones is known mainly for her work with miners but she was also an advocate of children’s rights. Monica Kulling’s On Our Way to Oyster Bay: Mother Jones and Her March for Children’s Rights (ages 7-10) recounts the true story of a protest march that she led starting in Philadelphia on July 7, 1903, and ending two weeks later in New York City. Over 250 children and adults made the trek with her, and when they passed through towns along the way, she would give public speeches about the evils of child labor in the factories in cities across the country.

The goal was to finish the march at the summer home of President Theodore Roosevelt in Oyster Bay on Long Island. When they got there, Roosevelt, not surprisingly, refused to meet with them. While there was disappointment among the marchers, Mother Jones considered the long journey a success, as several years later there were child labor laws passed by the state legislatures where they had marched.

This fictional account introduces that event in a picture book format to young children, and the attractive illustrations by Felicita Sala complement the story perfectly. This book would be particularly useful to teachers when discussing how children lived before there were any legal protections for children from extreme exploitation.

Two books about Clara Lemlich

Another picture book, Brave Girl: Clara and the Shirtwaist Makers’ Strike of 1909, with text by Michelle Merkel and pictures by Melissa Sweet (ages 4-8), tells the story of the early life of a real person named Clara Lemlich. Clara and her family had fled the anti-Jewish pogroms of the Russian empire and emigrated to New York City in 1904. Soon after her arrival, 16-year-old Clara was put to work in a garment factory where she worked long hours in stifling heat behind locked doors. At night Clara found some respite through reading books from the public library.

Although young, Clara was a fighter, and she was instrumental in organizing a garment workers union, leading them in a general strike of all garment workers throughout the city. After a long struggle, the garment bosses recognized the union and conditions in the shops improved.

While aimed at older preschoolers and early elementary students, Markel does not shy away from describing the brutality of hired thugs and the police: Clara was arrested 17 times and had six of her ribs broken. But this is ultimately an uplifting story of how one young person, through perseverance, can have a tremendous impact on other people’s lives.

Fortunately, young adults who might be interested in Clara but would rather read books for their own age group are in luck. Melanie Crowder has written a novel in verse (a format increasingly popular among YA—young adult—readers) that expands on the picture book and presents Clara’s story from her perspective as a teenager. Audacity (ages 12-18) is a moving, emotionally affecting read in which Clara’s innermost thoughts and feelings lend complexity to her story, and the verse-novel configuration of the text is successful in situating the reader inside Clara’s head: “Ours is a life of darkness and lamplight. / We know that outside the shop / the autumn sun shines— / only we never see it.”

We feel Clara’s frustration in attempts at organizing: “After work, / outside the grimy doors / of an underwear shop, / Pauline and I / press circulars / into the sweaty hands / of workers held at their stations / without compensation / long after the workday / is done. / We say, / ‘There is power in organizing.’ / We say, / ‘You do not have to suffer / alone.’ / They take the papers, / but sometimes / it seems / as if only the birds / are listening.”

We soon see whose side the legal system is on: “The magistrate steeples his fingers / like a man in prayer / ‘You are striking / against God and Nature, / whose law is that / man / shall earn his bread / by the sweat of his brow. / You are on strike against God!’ / If you ask me, / God knows / what little bread we get / is nothing close / to what we have earned / for all that sweat.” And we know when Clara finds her true calling: “All my life / I have been taught / a daughter should be good, / obedient. / That is one thing / I have never been. / But I have also been taught to give / without the thought / of ever getting back, / to ease the suffering of others / That, / I think / I will be doing the rest of my life.”

Clara did do that for the rest of her life. She joined the Communist Party in 1926 and was a co-founder of the United Council of Working-Class Housewives, which raised funds for workers on strike and did cooperative childcare. She also continued her union work, and even into her 60s Clara was still very politically active, demonstrating against the 1953 executions of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and the 1964 CIA-sponsored coup in Guatemala. Until she gets her own biography for young adults, Audacity—a National Jewish Book Award Finalist—is the best insight we have into the mind of this fascinating historical figure.

A photographer’s influence

While no one individual could be said to have been primarily responsible for the passage of child labor laws, photographer Lewis Hine comes close. While learning his trade in photography, Hine was appalled observing the conditions that child laborers had to endure, and he took a position as an investigative photographer with the National Child Labor Committee. He traveled throughout the country taking pictures of children at work.

Factory and mine owners did not want people to see such pictures, and Hine was constantly threatened and harassed. But he kept at it, often introducing himself as a fire inspector, an insurance agent or a photographer of factories and machinery in order to get inside the shop. When his photographs were published in newspapers and magazines, people were outraged by what they saw and public opinion began to shift heavily against employers of children. Hine was sent on lecture tours where he showed slides of children at their jobs. Hearing about children’s working conditions was one thing, but actually seeing the blank looks on their faces had a much more dramatic impact.

Children’s rights organizations began to petition Congress, and Congress responded by passing child labor laws in 1916 and 1918. But the United State Supreme Court said those laws violated the rights of states to determine their working conditions for children and they were ruled unconstitutional. In 1924 a constitutional amendment was sent from Congress to the states, but many states refused to ratify it, and so it never became federal law.

It wasn’t until 1938 that the Fair Labor Standards Act provided some protection for child workers, and in 1949 stronger regulations were passed by Congress that prohibited the use of child labor in commercial agriculture and many other businesses. Award-winning author Russell Freedman has made Lewis Hine’s story accessible to elementary and middle school-age children in his Kids at Work: Lewis Hine and the Crusade Against Child Labor, and while not a pretty tale, it is one of the best books to document this long shameful period in this country’s history.

Bread and roses, too

The Bread and Roses Strike of 1912 in Lawrence, Massachusetts, is the backdrop for a story of two children whose lives became intertwined because of the labor action. Rosa is the daughter of Italian immigrants who are employed at the local mill when they and the other workers have decided to go on strike. The teacher at Rosa’s school tells her students, “I’m sure your parents don’t want a city under mob rule, but if they listen to the rabble-rousers and go out on strike, that may well happen.” But her mother and sister tell her that the strike is necessary, leaving Rosa confused as to who is right. Jake is a young boy who works at the mill and usually sleeps in trash bins so he doesn’t have to go home to his physically abusive alcoholic father. But when Jake finds his father dead, he panics and decides to leave town before he is blamed.

When the mill owner’s goons begin to use violence against the strikers, the workers send their children to live with sympathetic families in another town until the strike is over. Jake stows away on the train where he sees Rosa and persuades her to say that he is her brother, Sal. They are taken in by the Gerbatis, an Italian family who treat them with love and respect. When Rosa hears that her mother and sister have been beaten by the police and thrown in jail, Rosa wants to go help them but the Gerbatis ask her to stay. Jake likes the Gerbatis as they have been kind to him, something he has never experienced. But he doesn’t trust anyone and plans to rob Mr. Gerbati’s safe. Mr. Gerbati catches him in the act, but instead of turning him over to the police, he talks to Jake to try to understand why Jake felt that he needed to steal. Jake tells him about his past and Mr. Gerbati forgives him.

Finally, the strike is over. The workers have won and Rosa is able to return home. Jake has found a home and a job with the Gerbatis and has been transformed—just as the conditions at the mill have been transformed as a result of the strike. Katherine Paterson’s Bread and Roses, Too (ages 10-14) does a wonderful job of taking the reader back in time to get a sense of what life was like for millworkers in the early 20th century and showing how union solidarity can make all the difference.

Massacre in the mines

While working conditions for children were horrible in the factories, those in the mines were just as bad, if not worse. Boys who worked in the coalfields were called “breakers” as it was their job to break apart bits of coal and remove impurities as it moved past them on a conveyor belt. This was extremely hazardous work, as boys didn’t wear gloves, and sharp corners of the coal bits would often cut their fingers. Many boys lost limbs or were crushed to death if they got caught under the conveyor belt. Contracting asthma and black lung disease was a common occurrence.

In Pat Hughes’s The Breaker Boys (ages 9-14), Nate, the son of a coal mine operator, is an unhappy kid who has been sent home from boarding school. Not wanting to be around his upper-class family, Nate rides his bicycle every day into the company town where the miners and their families live. He meets a young Polish boy who is a breaker and they develop a friendship due to their mutual love of baseball. Nate, of course, can’t tell Johnny or any of the other breaker boys he meets who he really is, as that would be the end of their friendship.

When Nate hears that the miners are planning a march to the mine in nearby Lattimer in support of a strike, he sneaks away from his family to see it. What he sees is the sheriff and his deputies shooting at 300-400 unarmed peaceful marchers. When it was over, at least 19 miners had been killed, many of them shot in the back, and up to 49 more had been wounded. This was a real event—the “Lattimer Massacre”—and it occurred on September 10, 1897. In the aftermath, Nate saw that some newspapers called it a “massacre,” while others said it was “a terrible riot by a mob.” But Nate knew what he saw. The novel ends with him returning to boarding school as his parents had wished. The Breaker Boys tries to be evenhanded about the incident, but the reality of what happened and who was at fault was clear. This is a tragic story of class conflict and the difficulties of sustaining friendships across class lines.

Many teachers will tell you that one of the best ways to learn about history is to put the student in the shoes of a person at a particular historical time and place. That’s exactly what The Child Labor Reform Movement: An Interactive History Adventure does. Modeled on the popular “Choose Your Own Adventure” series, where the outcome of the story depends on choices that the reader makes as a character in the story, this title allows the reader to become either a boy working in a cotton mill, a 10-year-old girl in New England, or a newspaper boy in New York City.

In each scenario, the girl or boy is presented with options of taking certain actions or not, which gives the reader a sense of the kinds of lives that these children had. Being a child laborer meant that the girl or boy had limited options as they had virtually no control over their work lives. With three different storylines, 49 choices and 23 potential outcomes, the reader can get a better understanding of what these children went through than just learning facts about that historical period.

This book is a good choice for reluctant readers as they will want to explore all the different outcomes for these children. As a result, those readers will probably have even more questions they want answered. And that’s a good thing.

Comments