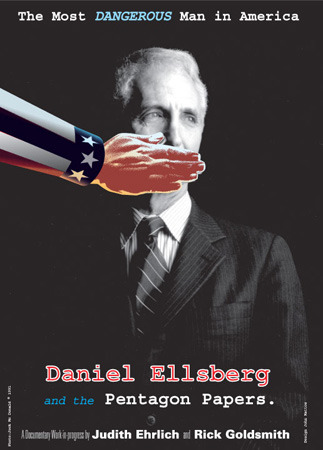

“The Most Dangerous Man in America“

Directed by Judith Ehrlich and Rick Goldsmith

2009, Not Rated , 92 min.

WASHINGTON (PAI) — We usually don’t use The Washington Window as a movie review, but we’re going to make an exception, and urge you to see “The Most Dangerous Man In America.”

The movie is actually a documentary about the Pentagon Papers case, the secret study of how the U.S. was involved in the Indo-China war and the executive branch lies that permeated the long struggle.

That definitive history was made public by Daniel Ellsberg and his colleague, the late Anthony (Tony) Russo, top researchers at the Pentagon-funded Rand Corp., think-tank in Santa Monica, Calif.

Narrated by Ellsberg, who often talks of the turmoil he went through as he reviewed the history — and the lies — of the war, the film also touches on some key issues in U.S. life today, and the impact of the Pentagon Papers case on subsequent history. To recap:

In 1967, with the war already going badly, then-Defense Secretary Robert McNamara commissioned the huge study. It had all the history of the conflict, including unseen history of how presidents from Harry Truman through Lyndon Johnson lied to Congress and the people about our involvement in Indochina.

Ellsberg, originally a war supporter (one recreated scene from his Pentagon service has him calling military people in Vietnam for evidence of Viet Cong “atrocities” to justify U.S. escalation) turned against the war while reading the Pentagon Papers’ wholesale revelation of the lies and cover-up. He determined to make them public.

He tried Congress. Lawmakers — even antiwar lawmakers — were too fearful of Johnson, his successor Richard Nixon, and public reaction to act. One little-known junior senator, Mike Gravel, D-Alaska, read parts of the Pentagon Papers into the record of a subcommittee he chaired. He was ignored.

So Ellsberg turned to the press — the now-derided and shaky “mainstream media.” He shared all of the thousands of pages of the Pentagon Papers, carefully photocopied, with The New York Times. After its own bitter internal battle over publishing top secret papers, documented in the film, the Times started printing the Pentagon Papers — with accompanying stories — in 1971.

Nixon reacted with a court injunction to halt the Times, the first time the U.S. government tried to censor a newspaper in advance — a tactic common in totalitarian countries. Then the Pentagon Papers turned up in The Washington Post. Nixon stopped that, too. But 15 other papers nationwide, including the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the Boston Globe, the Chicago Sun-Times and the Los Angeles Times, picked up the ball. CBS, NBC and ABC reported on each installment.

The Supreme Court called a halt to Nixon’s censorship, by a 6-3 vote. But what was a trusting relationship between the executive branch and the press, already frayed by the war itself — what reporters saw on the ground did not jibe with what the Johnson and Nixon administrations and their generals were saying — was broken.

Ellsberg himself started as an anonymous source for the Pentagon Papers. But his name was quickly revealed, the film shows, and Nixon blew up.

In excerpts of his infamous tapes, played in the film, Nixon, using his usual expletives (they’re not deleted), orders his staff to destroy Ellsberg.

How did Nixon try to do that? His White House set up its own “Special Investigations Unit,” to get the goods on Ellsberg — by burglarizing the office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist. That unit is also known as “The Plumbers” to help stop leaks. Yes, those “plumbers,” the ones who later burglarized the Watergate.

And we know what happened as a result of that. (Nixon also tried to sway federal judge W. Matt Byrne, hearing the case against Ellsberg, by offering him the job of FBI director. It didn’t work. And when the plumbers’ burglary was exposed, Byrne threw the Ellsberg case out of court, the film notes.)

What are the lessons for us in this? Well, one, Ellsberg says, is people must stay ever vigilant and question what their leaders say. Demand proof, not just assertions, because leaders lie. He’s put that into action. Ex-Marine Ellsberg, now in his late 80s, is shown near the end of the film speaking at a protest against George W. Bush’s war in Iraq. That, of course, is another war built on presidential lies.

Another lesson is the value of an independent press strong enough — and well-off enough — to try to be objective and investigative. Do today’s papers have the guts, and the cash, to throw reporters, time and money into uncovering another Pentagon Papers or a second Watergate? That’s not likely. As for blogs, TV and Fox…forget it.

And here’s another lesson we’ll draw, though it’s not original: Those who do not remember history are condemned to repeat it. So go see “The Most Dangerous Man in America.“ It’s a great history lesson.

Comments