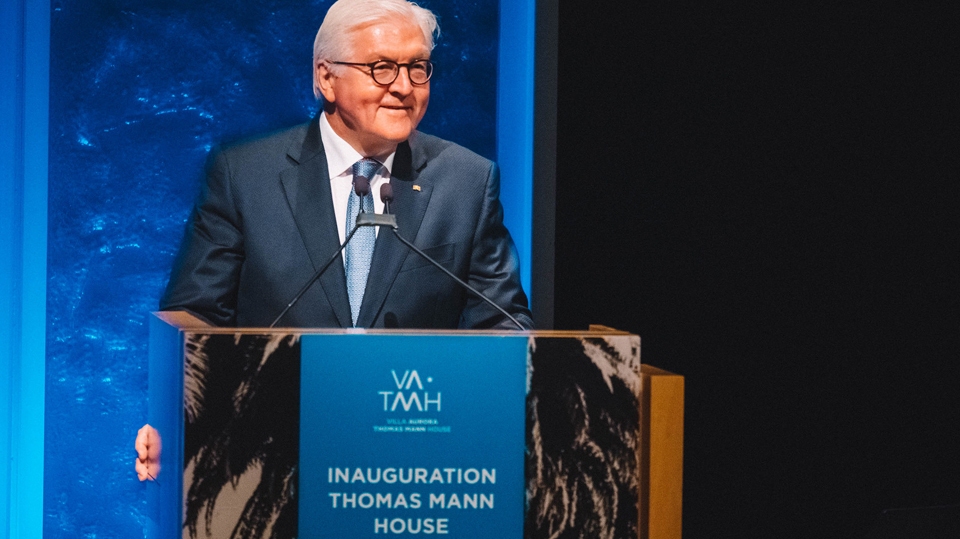

LOS ANGELES—Some fresh insight into the mind of the 16th president of the United States came to this city from the current president of the German Federal Republic. In a speech delivered here on Tuesday, June 19, President Frank-Walter Steinmeier recalled what may be Abraham Lincoln’s most famous words: “that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

In that immortal phrase from the November 19, 1863, Gettysburg Address, President Steinmeier observed, Lincoln does not say “from this nation,” nor even from this continent, but rather “from the earth.” Lincoln most certainly meant that the beacon of self-government should shine forth to all the other nations of the world.

“The world will little note,” Lincoln said, “nor long remember what we say here,” as he dedicated a part of the battlefield as a Soldiers’ National Cemetery. How wrong Lincoln was about that! What he said there, while the Civil War still raged on for the soul of the country, became one of the most stirring calls ever issued to complete “the unfinished work” of the radical American “proposition that all men are created equal.”

Steinmeier might have observed that numerous German socialists, some of them followers of Karl Marx, fleeing to America after the failure of the 1848 Revolution, joined the Union Army to preserve American democracy and free millions of human chattel from their chains.

Fifteen scholars from both sides of the Atlantic joined the German president at the Getty Center’s Harold M. Williams Auditorium to inaugurate the newly restored Thomas Mann House on San Remo Drive in Pacific Palisades, a toney neighborhood of Los Angeles, where the renowned Nobel Prize-winning German novelist and intellectual lived from 1942 to 1952. Mann had fled from one repressive regime, becoming a U.S. citizen in 1944, and then, in 1952, fled again from another, McCarthyism. Life magazine had labeled him a Communist fellow traveler; for Mann, life in the U.S. had become intolerably ugly. The Manns resettled in Switzerland, where he died in 1955.

The Mann home in Pacific Palisades has been called by some the “intellectual German White House in America.” It was a frequent gathering place for talks and discussions among some of the most luminary German expatriates, including Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Lion Feuchtwanger, Max Reinhardt, Fritz Lang, Arnold Schönberg, Hanns Eisler, and Bertolt Brecht.

The German government bought the former Mann property in 2016 for $13.25 million, and began restoring it to house a fellowship program for intellectuals and visionaries tackling contemporary global issues. As the then foreign minister of Germany, Steinmeier said that the house provided “a home for so many Germans who fought for a better future for our country and for a more open society.” The first Thomas Mann Fellows will start living in the house this summer.

Steinmeier recalled that in 1914, as World War I broke out, Mann spoke out publicly against democracy, but later felt appalled at himself, awakening out of his narrow nationalism. He visited the United States in the 1920s, during the troubled years of the fragile Weimar Republic at home, and recognized in America a different kind of nation, embodied in Walt Whitman’s poetry, based not on ethnicity but on shared commitment to constitutional principles.

If today’s Germany is perhaps the world’s most vital example of democracy—now far surpassing the United States by almost any measure—it owes that debt to America, said Steinmeier. Germans are deeply worried about their American friends across the Atlantic, but if 25 years ago the slogan “the end of history” was baseless, so, too are today’s cries about “the end of democracy.” The idea still retains much resilience, according to the German president.

German public opinion is divided now, he says. Some are giving up on the trans-Atlantic alliance and want to forget the U.S. Others believe their future will be better served through strategic and economic alliances with China or Russia. But the democratic vision and mission will continue, even as it needs constant work.

Steinmeier cited the occasion not long ago when he visited Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s gravesite in Atlanta together with Congressman John Lewis. The African-American representative from Georgia told him he was not discouraged: “I take seriously that part about the ‘more perfect union,’” Lewis said (in Steinmeier’s recollection and translated back into English). “Democracy will always have its shortcomings, but the important thing is to keep moving forward.”

If there are centrifugal forces at work in both the U.S. and Germany, there are also forces of democratic renewal, such as the Poor People’s Campaign, the gun control campaign, and all the women running for political office. These movements are not nostalgic, and not simply expressions of outrage, but are shaping a hopeful future. In a pointed message to America, Steinmeier appealed to preserve reason; otherwise democracy will not be possible.

He also reminded his listeners that populism can be used against anyone at will in the familiar human longing for absolutes. “Don’t retreat from politics,” he urged, “but engage. Apolitical simply means anti-democratic.”

Perhaps, he suggested, Americans, like Germans, need to look at democrats around the world (and maybe not regimes and countries as such—my inference) as their partners.

The fact that Germany sent its president to this conference is a clear sign of global concern over what is happening in the United States since November 2016.

President Steinmeier left immediately after his talk for an appointment that afternoon in Silicon Valley, accompanied by his ample security detail.

Human dignity “inviolable”

The day-long colloquium continued with three academic panels. In “Diversity and the Search for a Common Ground,” moderator Helmut K. Anheier opened by citing Article 1 of Germany’s Basic Law (Constitution), which states that “human dignity is inviolable,” an almost direct quote from Mann’s 1938 essay “The Coming Victory of Democracy.” In the wake of Germany’s offer of asylum to one million refugees from war-torn nations in the Middle East, Germany now has, according to Anheier, the same percentage of immigrants as the U.S.

Jutta Allmendinger, a current Thomas Mann House Fellow, has researched immigration and public opinion in Germany. There is greater segregation now in Germany than ever, though it is not specifically along ethnic lines, but rather according to age and social and economic status. Public funds support private schools, and as a result, there now exist exclusively migrant schools. Public space, where members of diverse communities can mingle and familiarize themselves with one another, have almost evaporated: People don’t even shop in the same stores anymore. Her solution to increase social cohesion is to invest a lot more in schools, not just to educate young workers for the labor market, given how many jobs of the past already do not exist, but to educate for humanity.

Miguel Suárez-Orozco studies immigration patterns in both the U.S. and Germany. “We love immigrants in the past,” he says, “but we panic in the present. The same anxieties echo through the ages.” Immigrants from Germany are still, historically, the single largest national component to the American population. The most salient difference between the migrant communities in the two countries is that some 11 million immigrants in the U.S. live in the shadow of the law as undocumented as de facto members of the nation, but not de jure. This is not the case in Germany, where every immigrant has papers and defined rights. He also stresses the importance of education: “Connecting with immigrant-origin children is the existential challenge of the future in both the U.S. and Germany. Without that connection there cannot be a happy future for our countries.” Immigrant children in America, he said, are learning English far faster than previous generations, and he pointed to ever higher rates of exogamy—people marrying outside their own group—as possibly leading to less segregation in the future.

Feeling a need for protection

In “Status Panic: The Fear of Social Decline in a Democratic Society,” moderator Nikolai Blaumer introduced the subject of emotions, fears and social phobias as factors in the current sense of malaise. Panelist Heinz Bude opened by saying that democracies are suffering a “nervous condition.” Many different identity groups today feel in need of “protection”—workers, students, families, elders, LGBTQ, commercial fishing, farmers. As longterm political parties lose their following, voters are more receptive to the appeal of charismatic figures who will “protect” them. Majorities share this easily exploited feeling of defenselessness.

The old model of the American dream, Bude says, is fast disappearing. Working hard, dreaming big, holding fast to your commitment, don’t seem to work today. At any stage one might make a wrong decision—the neighborhood you live in, the school you go to, the job you train for—and success eludes us owing to our own bad choices. We have moved, he says, “from the promise of advancement to the threat of exclusion.” He pairs this perception with the number of workers in dead-end service jobs, and also professionals and middle-class workers, whose jobs are now in decline. You are punished because even though you have the same education and the same drive as your neighbor, you just “bet on the wrong horse.” With anger, hate and resentment rising, you fear migrants taking your place; you fear being ignored. After the financial crisis of 2008, he says, you fear capitalism. The challenge is “How can we protect people without saying some deserve it and some don’t?”

Claire Jean Kim’s talk took a different tack: “Fear, Hatred, and the Dream of Racial Restoration.” It’s commonly said that race fear and fear of change produced Donald Trump’s victory. Kim answers that “fear” is a more socially acceptable interpretation: What really won was racial hatred. The American social order is founded on Black subjugation, from the beginning of slavery to the present. Racial power has merely reconfigured itself. Police willfully still murder Black people who are homeless, who are walking, who are driving, in other words, who are occupying public space to which they have no right. The killers cite their “fear” as a defense.

“The longing for white dominance has never been lost,” Kim says. “Donald Trump connects to that mood. He says, ‘To all of you who are tired of apologizing for being white, I am your man.’” The Nazis studied Jim Crow laws as a model for their race policies.

“Democracy is more aspirational than real,” Kim says. “It’s not the powerless who create these categories—it’s those in power. To talk about our common future without crediting the legitimacy of oppressed people’s experiences just sounds coercive.”

The three panels also included student commentators who were allowed time for brief responses—space does not permit here to elaborate more fully on their remarks. But Elizabeth Clark Rubio’s contribution struck me: She is writing her dissertation about undocumented Asians in the U.S. who barely register in the public discourse. She claims there are 800 Asian students without papers at her school alone, University of California, Irvine. Asians are held up to the nation as the “model minority” who fulfill the American dream in a country that is “foundationally anti-Black.” But how do we position the Asian struggle within the larger civil rights vision? Also, she says, the Dreamer narrative is itself flawed. Designed to appeal to kind-hearted people with the claim that these young people arrived here “through no fault of their own,” doesn’t that by implication reject their parents—whose “fault” it was?

Written off as unnecessary

In the last panel of the day, “Expulsions: Shifting Borders of Democracy,” moderator Steven Lavine, founding director of the Thomas Mann House, referred to “whole populations being written off as unnecessary”—forgotten, displaced, marginalized, dispossessed, evicted, all these words surfaced.

Ananya Roy led off with a global indictment of spatial inequality—one of her slides showed side-by-side images of a $500 million home in nearby Bel Air and the homeless tents of downtown L.A.’s Skid Row. She referred to biopolitics and necropolitics: Who will live and who will die as a result of the policies we enforce? If there is a “coming victory of democracy,” she speculated, referring back to Thomas Mann’s 1938 essay, it will not likely be in the North Atlantic countries, but in the global South, where there are more collective actions by masses of poor people holding their governments accountable.

Fonna Forman and Teddy Cruz explained some of their work in and between the single largest cross-border city in the world, the San Diego-Tijuana metropolis. Their slides included one showing rates of taxation and comparative income inequality. The two peaks came in 1926 and 2006 (although the data did not seem to go past that year and I suspect if updated the inequality might be far greater now). Not surprisingly, in the middle years, the New Deal era, we saw the highest investment in public infrastructure, the arts, housing and healthcare. “Public was not a forbidden word.” In today’s “anti-tax, anti-public, anti-immigrant” environment, we are “committing civic suicide.” We need to create new social norms of inclusion, enlisting the powers of non-profits, communities, universities, philanthropists, government and the private sector. We need to democratize access: Rosa Parks sat where she “did not belong.”

Wanting more clarity

I came away at the end of the day impressed by the research and erudition of the academics, and their evident passion for democracy. I also came away wanting more clarity.

If the day served in part to introduce German and U.S. scholars to each other in the launching of the Thomas Mann House, I would have liked to hear some comparison of the two countries regarding the influence of the One Percent’s money in our electoral and governance process. Surely when we speak here about “the struggle for democracy” this point is absolutely unavoidable, not to mention our discriminatory election laws, gerrymandering and the Electoral College itself. It can’t be that oligarchical in Europe today, can it?

It almost seemed as though, with notable exceptions, most of the speakers accepted uncritically the high school civics textbook explanation of how democracy works—checks and balances and all that. But it hasn’t operated that way for decades—and never has, especially if you’ve been among America’s many “despised” populations.

A little reaching out past Germany and the U.S. might have been useful, too. I have elsewhere written about social democracy in Scandinavia, and without intending to sanitize their problems or glorify their systems, I wonder if the kinds of fear and anxiety that characterize American life these days exist there. Do so many groups of citizens feel so much in need of “protection” that they would look to a charismatic leader to save them? Or is universal protection from cradle to grave—health, education, labor, family, women, immigrant, etc.—simply available to everyone without competition? I’m prepared to stand corrected, but it seems to me that you’d really have to set your mind to it to be marginalized or excluded in those countries.

The example of global South countries that Roy mentioned might have been made more explicit so the audience could know what she is talking about. I am thinking of China, Cuba, Vietnam, South Africa, Bolivia, Venezuela and Brazil, just to name a few places, where social policies have demonstrably enhanced democratic access—not always in simplistic North American terms like voting, but in healthcare, income, housing, security, pensions, social peace and personal safety, where millions of people have been lifted out of abject poverty into living-wage jobs. The fact that some of these advances have been made under the guiding star of socialism is certainly worthy of note and bears much deeper analysis.

How much progress toward democracy we can make while climate change threatens our existential global security was only barely touched on during the day. It must be calculated into any further discussion. One day’s colloquium could hardly cover everything.

The struggle for democracy is in high gear—or as they say in the global South, a luta continua, the struggle continues. It’s no time for despair: Signs of re-democratization are evident everywhere despite the formidable odds.

As I was finishing this writing, word came through that Trump has been publicly shamed into issuing an executive order rescinding his repulsive family separation policy at the southern border. His new policy says families (well, parents and children, but not necessarily other relations) seeking to enter the U.S. as immigrant workers or candidates for asylum will be kept together—in jail! A minor but significant victory we must build upon.

MOST POPULAR TODAY

‘Warning! This product supports genocide’: Michigan group aims to educate consumers

Hold the communism, please: SFMOMA’s Diego Rivera exhibit downplays artist’s radical politics

After months of denial, U.S. admits to running Ukraine biolabs

“Trail of Tears Walk” commemorates Native Americans’ forced removal

Ohio: Franklin County treasurer attends Netanyahu meeting, steps up Israel Bond purchases

Comments