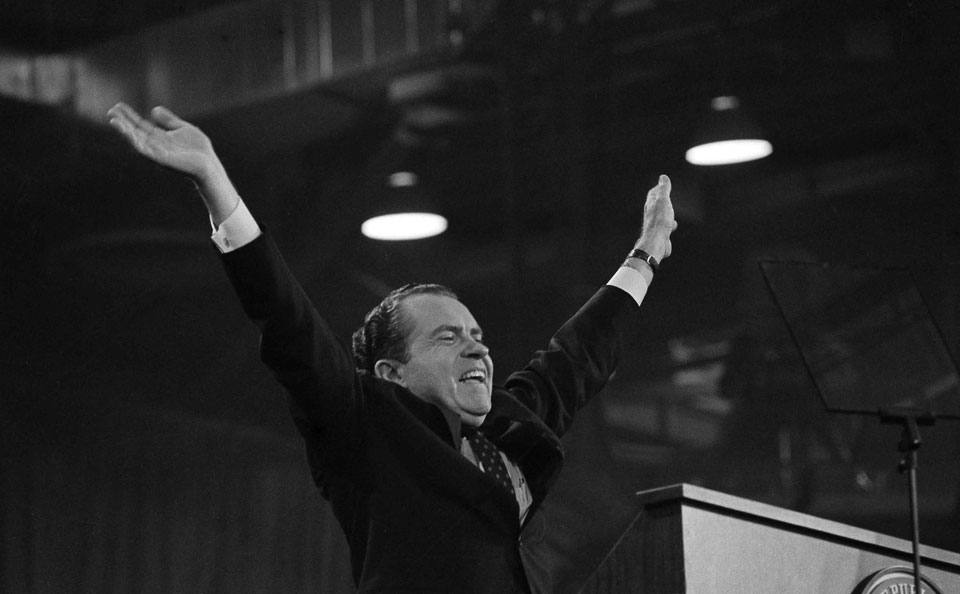

Fifty years ago, the National Convention of the Republican Party took place at Florida’s Miami Beach Convention Center, August 5-8, 1968. Richard M. Nixon, former vice president under President Dwight D. Eisenhower, was a clear frontrunner for the presidential nomination. He had run as the Republican nominee in the 1960 election, losing to Democrat John F. Kennedy.

During the last two days of the convention, Black Americans protested militantly in nearby Liberty City, frustrated by America’s failure to address deep-seated issues in the community such as discrimination, segregation, poor housing, exploitation, unemployment, police brutality and—in the consciousness of all Americans at the time—the increasing number of deaths in the Vietnam War which disproportionately affected communities of color. Some also resented competition for jobs against favored Cuban refugees.

This convention saw the debut of the “New Nixon,” who in this election devised his “Southern strategy.” Many whites in the Southern states vehemently opposed racial integration, voting rights for Blacks and other liberal policies of the national Democratic Party, the late John F. Kennedy and his successor, the incumbent 36th President Lyndon B. Johnson. Johnson had announced a few months earlier that he would not run for re-election. Nixon’s aim was to peel off the “solid South”—historically solid for the Democratic Party—and, based on racism, turn more than a quarter of the country Republican. That scheme worked, and continues with only intermittent challenge to the present day.

Nixon turned to a perceived moderate, Maryland Governor Spiro T. Agnew, as his vice-presidential choice. As governor, Agnew impressed Republican leaders when he summoned Black civic, religious and political figures in Baltimore to the local State Office Building, following the disastrous April 1968 disturbances which enveloped Black sections of Baltimore, along with the rest of the nation, after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis.

But what Nixon might have valued more, in keeping with his Southern strategy, is that Agnew complained of the Black leaders’ lack of support for a number of programs his Republican administration introduced for the minority communities in the city. When Agnew publicly cited their lack of enthusiasm for his GOP, many in the audience walked out. Nixon may well have seen that response as exerting a positive appeal to racist whites.

Nixon was nominated on the first ballot, far outpacing candidates Nelson Rockefeller, Ronald Reagan and others. In his acceptance speech he deplored the state of the union:

“When the strongest nation in the world can be tied down for four years in Vietnam with no end in sight, when the richest nation in the world can’t manage its own economy, when the nation with the greatest tradition of the rule of law is plagued by unprecedented racial violence, when the President of the United States cannot travel abroad or to any major city at home, then it’s time for new leadership for the United States of America.”

He also summoned his “good teacher” Eisenhower, president 1953-61, who for health reasons did not attend the convention, and inspired the delegates saying, “Let’s win this one for Ike!”

Meanwhile, back in the hood…

A group of Black organizations in Miami called for “a mass rally of concerned Black people,” to take place on August 7, 1968, at the Vote Power building in the neighborhood of Liberty City. Sponsors were the Vote Power League, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and numerous other organizations.

After a white reporter was ejected from the “Blacks Only” rally, Miami police exacerbated tensions by sending five cars and a carbine unit. A white man in a car displaying a George Wallace for President bumper sticker attempted to drive through the area, but as he passed the Vote Power building, his automobile was met with a barrage of stones and bottles and crashed into another car. The driver fled on foot, and his car was overturned and set on fire. Protestors ransacked white-owned businesses in Liberty City’s commercial district, and police eventually broke up the disturbance with tear gas.

Florida Gov. Claude Kirk, and SCLC president Ralph Abernathy, both attending the Republican National Convention, and Metro-Dade County mayor Chuck Hall arrived for a meeting with community leaders, but no actions to resolve any community issues were agreed on. Gov. Kirk proposed resuming the discussion at 11 am the following day.

The next morning, August 8, Kirk and local authorities only sent emissaries without appearing themselves. The outraged community broke out into even larger-scale violence than the previous day. Rioters stoned police, fire-bombed area markets, and looted white-owned shops. Miami officials requested assistance from the Florida Highway Patrol, which used a cloud of tear gas dispensed by a modified version of an insect-control machine to restore order.

That afternoon, Miami police, responding to what they claimed to be sniper fire, killed two residents and left a fourteen-year-old boy with a bullet through his chest. No weapons were found in the vicinity. Police shot and killed an unarmed man in the Overtown neighborhood as well.

The Florida National Guard was called out, and a dusk-to-dawn curfew was imposed. Order was restored with the help of 200 sheriff deputies. Heavy rains the next day ended the protest.

Racial disturbance in Miami during the Republican Convention may have further emboldened candidate Nixon’s outreach for the white vote. He also promised he had a plan to end the Vietnam War, which he had criticized in his Convention speech, but as history records, he had no such plan and only deepened the war. His opponent in November, Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, was perceived as complicit with Johnson’s war and did not campaign convincingly about ending it. More American troops died during Nixon’s presidency than under Johnson’s.

Spiro Agnew, Nixon’s acerbic spokesperson against the rising antiwar protests by students, liberals and the media, resigned on corruption charges in 1973. And of course Nixon himself resigned in 1974 because of the Watergate scandal. It was left to his successor, his appointed Vice President, now President Gerald Ford, to hastily evacuate from Vietnam in 1975 when the National Liberation Forces of Vietnam finally overran the last American holdouts in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City).

Nixon’s Southern Strategy has held up demonstrably well in the years since 1968, and can be largely credited with Republican presidential wins in 1972, 1980, 1984, 1988, 2000, 2004, and 2016.

Sourced from Wikipedia and other sites.

MOST POPULAR TODAY

‘Warning! This product supports genocide’: Michigan group aims to educate consumers

After months of denial, U.S. admits to running Ukraine biolabs

“Trail of Tears Walk” commemorates Native Americans’ forced removal

Hold the communism, please: SFMOMA’s Diego Rivera exhibit downplays artist’s radical politics

Comments