In 2013, I interviewed CodePink co-founder Medea Benjamin, author of Drone Warfare, Killing by Remote Control, who asserted: “There were between 46 and 52 drone strikes under the Bush administration. And now there are over 400 – that’s not counting Afghanistan. So this has been tremendously increased under the Obama administration. If you look at Afghanistan the numbers are even more astounding – the last year where have figures for is 2012, and that’s 506 drone strikes, whereas there were very few drone strikes under Bush…. The CIA runs the drone program in Pakistan solely, not with the military. Then there’s a joint CIA-military program in Yemen, then the CIA is involved in a lot of use of spy drones around the world and in the proliferation of bases.”

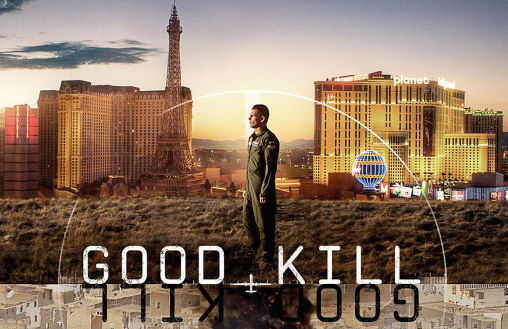

Now a feature film has been made with major Hollywood talents dramatizing the dubious Unmanned Aerial Vehicle program and the controversies surrounding it. New Zealand writer/director/producer Andrew Niccol’s Good Kill is a hard-hitting, thought-provoking movie exposing and opposing drone warfare in Afghanistan and Yemen. Fresh from his Oscar-nominated role in Boyhood, Ethan Hawke portrays pilot Major Tom Egan who, after repeat combat tours flying over the Iraq and Afghan theaters of conflict, is now stationed outside of Las Vegas. There he is deeply conflicted by his role in the UAV liquidation-by-remote-control project.

From the relative comfort of an air-conditioned trailer in a military base in the Nevada desert, the droners wreak Hellfire havoc on targets in other deserts half a world away. The fetching if kvetshing Zoe Kravitz, daughter of Lenny Kravitz and Lisa Bonet, plays fiery Vera Suarez, a Latina Air Force officer who has qualms after she joins the UAV team at the Nevada air base.

What Suarez bellyaches about are the moral implications (or lack of) of droning, which according to the movie (and Medea) is an imprecise method of murder which inevitably results in “collateral damage” – including the deaths of unarmed civilians, among them, alas, children, women and the aged. According to the film, this killing of casualties, whose only crimes are being at the wrong places at the wrong times, is acceptable to the CIA. You know the CIA: That U.S. organization (your tax dollars at work) that LBJ called “Murder Incorporated” (hey, it takes one mass murderer to know another!), which has overthrown democratically elected governments from Iran to Guatemala to Chile, etc., tortured more dissidents than the Spanish Inquisition, and so on.

Suarez denounces the CIA-directed droning of non-combatants, as U.S. “terrorism” and a “factory creating terrorists,” because of the widespread anger and blowback these killings provoke and spread. During one testy trailer exchange with her commanding officer, Lt. Colonel Jack Johns (portrayed by Bruce Greenwood), Suarez cheekily asks: “Was that a war crime, sir?” To which Johns replies: “Shut the f*ck up, Suarez!”

His conscience troubled, Major Egan can no longer “keep compartmentalizing,” as Johns advises him to. He has a drinking problem and his marriage to Molly (January Jones) is, like his liquor, on the rocks. Like Jeremy Renner’s lead character in 2010’s Best Picture Oscar winner The Hurt Locker (co-produced by Nicolas Chartier and Zev Forman, who also co-produced the far superior Good Kill), Egan has difficulty making the transition from the combat zone to the home front: He is still at war, “taking potshots” at people across the globe being surveilled by remotely piloted aircraft with their lethal payloads.

But unlike The Hurt Locker‘s PTSD-ed, traumatized psychopath, Egan finds a path back to his sanity. It’s a similar route blazed by veterans such as the courageous Ron Kovic, whom Tom Cruise depicted in Oliver Stone’s 1989 antiwar classic Born on the Fourth of July. He takes a stand against orders to shoot Hellfire missiles from a drone at civilians.

Meanwhile, the gung-ho Specialist Zimmer (Jake Abel) is the troop’s trailer trash, who represents the jingoistic dregs of military madness. Zim derides Suarez as “Jane Fonda” and quips about putting “warheads on foreheads.”

Perhaps Zim is one of the “gamers” whom the Pentagon recruits for its UAV program, which appears to play out like a video game (albeit one with extraordinarily high stakes involving life and death). The Las Vegas vibe and backdrop enhance the sense of the inherently risky nature of drone warfare. Good Kill‘s aerial footage, apparently shot in Morocco, has the look and feel of a video game, as it simulates what the Nevada-based airmen-turned-chairmen see on their computer screens as these not-so-Big Brothers watch Afghans and Yemenis from seats in their air-conned trailer. This cinematic technique has a Brechtian alienation feel, distancing film viewers from the action. Good Kill‘s combat isn’t as viscerally exciting as that depicted in more conventional, pro-war flicks, like American Sniper or John Wayne’s Sands of Iwo Jima. But that’s because this is an antiwar work of art that wants audiences to use logic and reason, not just emotion, when assessing the story onscreen.

Drone warfare, of course, is a compromise. On the one hand, the U.S. ruling class still wants to, you know, rule the world; while on the other, its ordinary people just want to get about the business of living their lives without endlessly fighting and dying abroad.

What’s a poor imperialist to do?

Use advanced technology to fight in cowardly ways that are less likely (at least in the short term) to directly, immediately endanger Americans, so the masses won’t rebel against these imperial misadventures generating U.S. body bags, rising up from the streets to the barracks, like we did during the Vietnam War. Drone warfare is just the latest strategy for American exceptionalists to project U.S. power abroad and stick their noses into people’s business overseas, without triggering widespread protests at home. Because, you know, it’s only a bunch of subhuman sand N-words getting Hellfired.

Meanwhile, back at the review:

In that interview with Medea Benjamin I asked: How are the subjects of drone warfare’s targeted killings selected? The feisty organizer replied: “They’re supposed to be high level Al Qaeda operatives that pose an imminent threat to the U.S. and American personnel and citizens. There’s supposed to be no way to capture them. We have not been told how they try to capture them or what constitutes a ‘high level Al Qaeda operative’…. The ‘kill list’ is calculated in the ‘terror Tuesdays’ at the White House every week, where the president and his advisors – including CIA – ‘nominate’ people to be on the kill list. Ultimately, the president has to sign off on the kill list. From what we know it looks like there are two separate but overlapping kill lists: One is the CIA kill list, the other is the military kill list. It’s speculated that [having two lists] makes it more difficult to have Congressional oversight and the executive is not thrilled about having that.”

To paraphrase Marshall McLuhan, it would seems that the Medea is the message. Andrew Niccol – who wrote and directed the 1997 sci-fi pic Gattaca, also starring Hawke, and 2005’s arms dealer drama Lord of War – has given dramatic form and expression to the anti-drone critique of antiwar activists, such as not-so-private Benjamin. Right on target, Good Kill is a good film, a thinker’s thriller.