Bernie Sanders’ socialist presence in the Democratic presidential primary promises, hopefully, to keep the much-needed conversation on income inequality front and center in our national debates.

Unfortunately, the discussions of income inequality too often get subsumed into questions about the health of the U.S. economy overall. Yet, the health of the economy and reducing income inequality are not the same discussions at all. In fact, many proposals to prop up or restore the health of our current economic system are actually at odds with improving the standard of living for workers in the U.S. For example, while “Right-to Work” laws might to some extent be effective in creating business-friendly environments attractive to corporations, in states with such legislation workers tend to receive less in both wages and benefits.

Nonetheless, despite this data, Governor Bruce Rauner of Illinois is pushing for right-to-work legislation by creating “economic empowerment zones” in which local communities could decide if workers can opt out of paying dues to the unions, which protect them in the workplace and bargain for their wages and benefits. In this case, empowering the economy means disempowering workers and decreasing their wages and benefits.

Gov. Sam Brownback‘s efforts to improve the local economy in Kansas by dramatically slashing taxes on businesses and the wealthy overall has resulted in severe social decay, leaving a wasteland without adequate revenue to sustain public schools or vital social services.

So much for trickle-down economics.

But even the ludicrous pretense that the wealth redistributed to the top will trickle down has been dropped.

Donald Trump, for example, in a recent interview with The Detroit News actually outlined a plan to drive down wages even more, pointing the finger at autoworkers who, he believes, earn too high of a wage. Expressing dismay that Ford plans to open a factory in Mexico, Trump proposed an alternative strategy for lowering labor costs that would keep jobs in the U.S. by closing plants in Michigan and moving production to more corporate-friendly regions: “You can go to different parts of the United States and then ultimately you’d full-circle-you’ll come back to Michigan because those guys are going to want their jobs back even if it is less. We can do rotation in the United States-it doesn’t have to be in Mexico.”

We see here no plan to address income inequality as a social ill but only to exacerbate it as a corporate benefit for the wealthy. Moreover, Trump reveals that the sought-after boosts in corporate profits are not intended at all to trickle down. The wealth only trickles up from wage reductions workers suffer, perpetrating another mass re-distribution of wealth from the bottom to the top.

For all their railing against calls for re-distribution of wealth, our nation’s economic elite seem to engage quite a bit in the practice.

Of course, even many of the most persistent arguments marshalled to defend policies aimed at addressing the wealth gap rely, typically, on their own brand of trickle up economics. Venture capitalist Nick Hanauer, for example, dismisses “the dire warnings of economic calamity [that] rain down” whenever the prospect of raising wages arises. He terms this alarmist response “Chicken Little economics,” documenting that these alarms have sounded with every substantial increase in the minimum wage since 1938 without the economic sky ever having fallen.

In urging New York to raise its minimum wage to fifteen dollars, Hanauer points to Seattle and San Francisco as cities that significantly increased its minimum wage to the benefit rather than detriment of their economies. Raising the minimum wage, so goes the argument, creates more able consumers, buoying the economy as a whole and causing wealth to trickle up.

Still, these arguments center on the question of whether raising the minimum wage-a small step in addressing income inequality-help or hurt the economy. They never question the current economic arrangement in any fundamental way. Consider, for example, some of the following headlines on stories covering this ongoing issue on CNBC.Com: “State Minimum Wage Hikes: Help or Hindrance?” and “Easy Street or the Breadline?: New Year Wage Hike Debated.”

From a progressive political perspective, what if we discover that raising the minimum wage would hurt the economy and result in job loss? For example, the Congressional Budget Office forecasts 24.5 million workers will benefit from a raise in the federal minimum wage to $10.10, but 500,000 workers would lose their jobs. Should we then cease to advocate for the infinitesimal redistribution of wealth that would help low-wage workers, who play a role in producing the wealth of our nation, meet their basic needs? Should the progressive position be that those working for low wages must continue to do so and stop asking for more, regardless of whether or not they can meet their basic needs on those wages, so that more people aren’t thrown out of work and the economy isn’t hurt?

Of course not, but progressives need to reframe the debate. To those who argue that raising the minimum wage will hurt the economy, we need to ask how smartly organized is an economy in which those who do vital and necessary work cannot afford to meet their most basic needs.

The health of an economy, it seems to me, should correlate directly to the health of the people living within it, not to their immiseration. If a healthy or strong economy requires that those who work within it to produce and distribute goods and services are not able to access those goods and services to meet their needs, then we need to question the human viability of that economy, not worry about whether we’re hurting the economy with our policies. Indeed, an economy that achieves health when the people working within it suffer is one that we need to hurt by dismantling and overhauling it. What we need to do is remind ourselves that the purpose of an economy is, in the most efficient way, to produce and distribute goods and services to meet the needs of those living within the economy. As the wealth gap increases, it seems clear our economy is not doing that. The economy is supposed to serve us; we aren’t supposed to serve the economy.

Malcolm X famously said, “We didn’t land on Plymouth rock. Plymouth rock landed on us.” We might adapt this saying: working people did not hurt economic health but so-called economic health could hurt working people.

This article is abridged from the original, which appeared on Politicus.

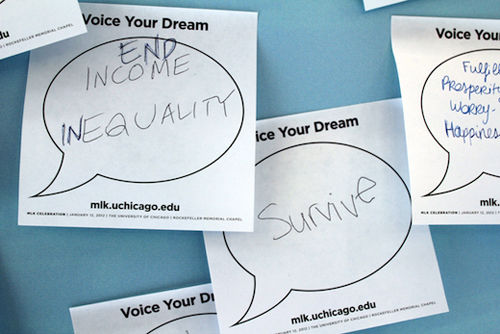

Photo: Quinn Dombrowski/Flickr/CC

MOST POPULAR TODAY

High Court essentially bans demonstrations, freedom of assembly in Deep South

U.S. imperialism’s ‘ironclad’ support for Israel increases fascist danger at home

UN warns that Israel is still blocking humanitarian aid to Gaza

Resource wars rage in eastern Congo, but U.S. capitalism only sees investment opportunity

Comments