Much-beloved California artist, teacher, and former poet laureate of Sacramento, Jose Montoya died Sept. 25 at the age of 81. Montoya played a leading role in labor, the Chicano civil rights movement, and the arts since the 1960s.

Montoya was born in New Mexico in 1932. His family later moved to central California where he grew up. The family first moved to Delano, Calif., birthplace of the United Farm Workers, before eventually relocating to the town of Fowler, 10 miles outside of Fresno. From the time he was 9 years old, he worked alongside his family in the fields picking grapes. His mother worked stenciling images in churches and homes to supplement the family’s income. Montoya assisted her in grinding pigments.

He later credited this experience as giving him his start as an artist.

After high school, Montoya, determined to not to become trapped working in the fields, enlisted in the Navy during the Korean War. After serving, he received GI Bill funds that enabled him to study at San Diego City College, and then to attend California College of Arts and Crafts (now California College of the Arts) in Oakland to obtain a teaching credential.

In 1969, Montoya and colleagues Esteban Villa, Juanishi V. Orosco, Ricardo Favela, and Rudy Cuellar were teaching art in Sacramento and were frustrated with the marginalization of Chicano artists. That same year, the struggle of the farmworkers in California made front-page news, with leader Cesar Chavez bringing to light the abuse and exploitation of the thousands of Latino field workers laboring in California agriculture.

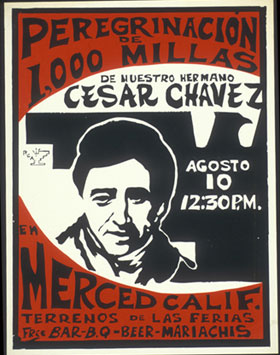

These artists formed an art collective which blossomed into a movement to support the budding farmworkers’ union, producing many vibrant and iconic posters and images associated even today with the UFW, including the famous “HUELGA” eagle flag. The collective at first called itself the “Rebel Chicano Art Front” and used the initials RCAF on screen-printed posters as a signature. The initials were the same as those of the Royal Canadian Air Force and the collective often heard queries about their connection to Canada and its air force. In an ironic response, the artists embraced the concept and renamed themselves the Royal Chicano Air Force, creating a fictional quasi-military identity that also underscored the militant politics of the labor struggle they were involved in.

The artists obtained vintage U.S. Air Force uniforms and a World War II Jeep, producing a strong public image during the era’s grape boycotts at grocery stores in California that gained the attention of the media. The artists also created a mobile art squad that loaded up a silk-screen press into a Volkswagen van, driving to agricultural sites and creating flags and posters for activists to use on the spot.

Despite their satirical military identity, the collective was committed to peaceful nonviolent work. Rudy Cuellar said, “Our bullets were our posters, our bombs were our prints.” The artists also aligned their identity with the political activism of Mexican political muralists such as Jose Clemente Orozco, David Siquieros and Diego Rivera.

“Commandante” Jose Montoya would become an organizer for the UFW, spending Fridays and Saturdays at Safeway supermarket grape boycott picket lines. In addition to supporting the UFW, the RCAF, taking inspiration from programs started by the Black Panthers, launched “Breakfast for Niños,” serving breakfast to schoolchildren in poor communities. They also started a community neighborhood art center in Sacramento – Centro De Artistas Chicanos – teaching silk-screening workshops and providing space to make art.

Montoya’s fellow RCAF founder Juanishi Orosco, in the 1995 documentary on RCAF entitled “Pilots of Aztlán,” said, “Cesar [Chavez[ recognized early on the importance of the artists’ community and how to best utilize them for the United Farm Workers movement. We don’t need to go back into the fields and help pick. Now we’ve moved beyond that. We’re artists, and we can say things that relate on large scales and address specific issues with our talents.”

Montoya taught and mentored students in arts and ethnic studies as a professor at Sacramento State University for 25 years. There he helped establish the Barrio Art Program, a hands-on university course of study that sends teaching students out into communities to teach art classes in under-served neighborhoods in a cross-cultural program.

On his death, UFW President Arturo Rodriguez and Paul Chavez, director of the Cesar Chavez Foundation, said, “We will always cherish Jose for how he inspired us as well as so many others through his art. But we will also remember him for the countless times when he walked picket lines, helped organize UFW events and fed the farmworkers during every major strike, boycott and political campaign. He was truly a servant of the farmworker movement and we will always be in his debt.”

Jose Montoya talks about the Royal Chicano Air Force (produced by UNITYLab):

Online archives of the Royal Chicano Air Force.

Video of Jose Montoya reading from his celebrated bilingual poem “El Louie.”

Photo: Poster by Jose Montoya announcing the “1,000-mile journey of our brother, Cesar Chavez,” an event held in Merced, Calif., year not given. Online Archive of California/UC Santa Barbara

MOST POPULAR TODAY

Zionist organizations leading campaign to stop ceasefire resolutions in D.C. area

High Court essentially bans demonstrations, freedom of assembly in Deep South

Afghanistan’s socialist years: The promising future killed off by U.S. imperialism

Communist Karol Cariola elected president of Chile’s legislature

Comments