An insider is spilling the beans on the great unsaid in charitable circles: You can’t ignore inequality and hope to fix an unequal world.

Inequality has a silver lining. At least the awesomely affluent think so. If we didn’t have grand fortunes, their claim goes, we wouldn’t have grand philanthropy. No foundations and handsome bequests for underwriting good causes. No gifts and grants that stretch up into the hundreds of millions.

Philanthropy, proclaims a new study from the global banking giant Barclays, has become “near-universal among the wealthy.” The rich among us, says Barclays, share “a desire to use” their wealth for “the good of others.”

But this “desire” doesn’t appear to be driving all that much sharing, as the researchers from Barclays themselves acknowledge. Some 97 percent of the world’s “high net worth individuals,” they note, do give annually to charity. Only one-third of the affluent give away over one percent of their net worth.

The rich, in other words, could afford to give away far more than they actually do. How much more? A dozen years ago, a public-spirited financial industry superstar – multimillionaire San Francisco money manager Claude Rosenberg – did his best to calculate the answer.

In the year 2000, Rosenberg-funded research would find, American households with incomes over $1 million could have given $128 billion more to charity than they actually did give and still ended the year holding a larger personal fortune than they had when the year started.

Claude Rosenberg died six years ago at age 80. The message he tried to deliver – that the super rich can afford to give far more to charity than they actually do – never really gained any traction in the public discourse over philanthropy.

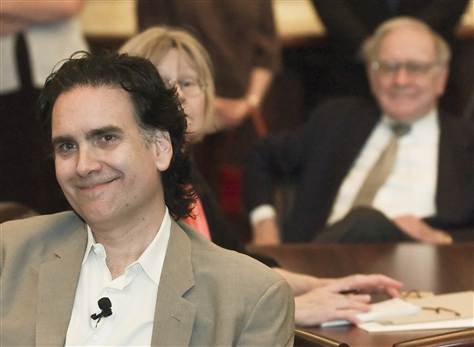

But now a second challenge to the philanthropic conventional wisdom has emerged, and this one figures to be tougher to ignore. The reason? The challenger just happens to be the son of the world’s fourth-richest billionaire.

This new challenger, Peter Buffett, isn’t arguing that the rich don’t give enough. He’s challenging the actual core of the philanthropic mindset, the notion that the rich, with their giving, are making the world a significantly better place. Buffett, in effect, is blowing the whistle on America’s entire contemporary philanthropic enterprise, what he calls our “charitable-industrial complex.”

Peter Buffett knows this complex from the inside. He runs a foundation his father Warren Buffett created and, over recent years, has watched U.S. philanthropy become a “massive business” that manages hundreds of billions.

Two weeks ago, in a New York Times op-ed, Peter Buffett began peeling off the halo that tops this mammoth philanthropic operation, and he continued that peeling process in an online interview.

In any elite philanthropic gathering, notes the 55-year-old Peter Buffett, you’ll see “heads of state meeting with investment managers and corporate leaders,” all of them “searching for answers with their right hand to problems that others in the room have created with their left.”

And the answers that do eventually emerge seldom discomfort the problem-creators. These answers almost always keep, Buffett charges, “the existing structure of inequality in place.”

Buffett dubs this comforting charade “conscience laundering.” Philanthropy helps the wealthy feel less torn “about accumulating more than any one person could possibly need to live on.”

They “sleep better at night while others get just enough to keep the pot from boiling over.”

That “just enough,” Buffett adds, can do long-term damage. Today’s philanthropists impose a stark corporate vision and vocabulary on the charitable world, pushing “free-market” principles, constantly demanding proof of “ROI,” return on investment.

Meanwhile, the global “perpetual poverty machine” rolls on – and philanthro-pists appear too busy patting themselves on the back to notice. Observes Buffett: “As more lives and communities are destroyed by the system that creates vast amounts of wealth for the few, the more heroic it sounds to ‘give back.'”

Buffett’s whistle-blowing is already having an impact. Those getting crushed by the “philanthropic colonialism” Buffett decries are circulating his critique to combat the “solutions” philanthropists are imposing upon them.

For instance, veteran Chicago public school teacher Timothy Meegan cited Buffett’s analysis in his push-back against the “venture philanthropists” now forcing “mass privatization” on Chicago’s school system.

Megamillions from the powerful Broad Foundation, Meegan shows, distort public policy decisions in Chicago, bankrolling a strategy that’s proliferating charter schools run by private operators while simultaneously defunding neighborhood schools, declaring them “failing,” and then shutting them down.

That same cause produced massive protests just a few months ago by the Chicago Teachers Union against the corporate-induced shutdowns. It was one reason CTU and Unite Here opposed Democratic President Barack Obama’s nomination of one of the richest women in the U.S., Penny Pritzker, to be Commerce Secretary.

As a Chicago School Board member – appointed by city Mayor Rahm Emanuel, the president’s former chief of staff – Pritzker enthusiastically supported the school shutdowns. And her Hyatt Hotel chain broke labor law, trying to smash Unite Here.

Concludes Meegan: “If allowed to continue, this philanthropic onslaught will leave Chicago without real public schools, only a network of tax-subsidized charters “whose investors will profit handsomely off of our kids.”

We don’t need, Peter Buffett contends, a philanthropy that helps turn “the world into one vast market.” We need instead systemic change “built from the ground up.”

Top-down change simply isn’t working. Not in Chicago. Not anywhere.

Sam Pizzigati, veteran labor journalist, edits Too Much.

Photo: Billionaire Peter Buffet is exposing what he says is the hypocrisy of the super wealthy curing with their charitable donations the very problems they create with their wealth. Nati Harnik/AP