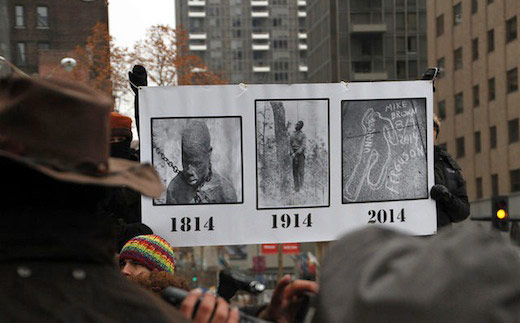

ST. LOUIS – Since the grand jury announcement that Michael Brown’s killer would not be tried for any crime, activists have worked to put the ongoing struggle for justice and equality within a historical context. In so doing they’ve built a new social and economic justice movement on the foundation left by those who struggled before them. On the afternoon of Nov. 25 the movement to build a better, more just and equitable, world moved forward.

Descending the front steps of the Eagleton courthouse, over 500 people poured into downtown, a newly created maze of detours due to the large numbers of police and National Guard present. Marching in the front row was the youngest member of Governor Jay Nixon’s Ferguson Commission, Rasheen Aldridge, a young African American “millennial” and a former fast food worker. Aldridge was unlawfully fired from Jimmy John’s for participating in a one-day strike for $15 and a union. Over the next ten months, the Ferguson Commission will explore and examine the conditions and causes of economic and social injustice there and his experience in this movement will undoubtedly bring an important perspective and new insights to these longstanding problems.

Turning onto North 4th Street, the crowd approached the Old Courthouse. Directly across a long lawn from the courthouse, the iconic St. Louis Arch holds the sky peacefully. The crowd stopped briefly, and many climbed the courthouse steps toward a small line of Parks Department workers in green uniforms blocking the top stairs. Others posed with a large bronze statue of Dred Scott and his wife Harriet. As police vehicles of every make followed behind, the crowd marched between the arch and the courthouse.

Standing between the two structures, their placement opposite one another is so apparent, one wonders how the two landmarks are related. The Old Courthouse, scene of the infamous Dred Scott case, stands as an empty monument to the racist policies of the U.S. government and the repressive power of the state. St. Louis Arch reaches skyward like two arms, fingers clasped together in prayer, perhaps, as if pleading with the powers that be. It seems a fitting symbol for the people and city of St. Louis. Far below, the shadow of the Arch fell through the afternoon onto the marchers below who, like the arch, held their arms up. Reaching for the sky, they chanted, “Hands up, don’t shoot.”

A short distance ahead, the Interstate 44 overpass rumbled. Keeping their pace in disciplined ranks, the marchers chanted all the way. Police vehicles moved to block the streets. Freshly painted correctional buses, idled within view.

Suddenly, the crowd turned, leaving the police blocked by a single line of people arms linked across the road; the rest moved toward the Martin Luther King Bridge.

Stopping traffic from both directions, the demonstrators took control of the bridge. As police scrambled in the distance, the crowd simply sat down. Not a single person spoke. A few looked down at the pavement, some held their heads in their hands, others smoked cigarettes, many focused their eyes above.

For four minutes, even the blocked traffic sat quietly. There it was starkly apparent that this is not only a Black issue. The array of people who observed that moment of silence showed that the fight against exploitation, institutional racism, and police violence is the fight of a broad coalition of people from all walks of life.

Their vigil complete, the crowd leapt to its feet. Holding up their arms, and shouting “Hands up, don’t shoot,” they marched toward the police waiting below. In the tangle of roads and construction beneath I-44, the SLPD was just starting to arrive in force against the demonstrators. With traffic stopped for miles in both directions, the crowd milled about briefly before sitting down. Up there on the elevated Interstate, the activists have placed themselves between two historic protests for labor and minority rights in St. Louis.

Fifty years ago the St. Louis Arch, which dominates the skyline to the south, was the scene of a civil rights action by two workers, Percy Green and Richard Daly, who climbed 125 feet up the yet to be completed structure and refused to come down for over four hours to protest the lack of minorities hired to work on the project.

While 15 years ago, just to the north of the protesters on I-70, 300 people, including Al Sharpton, formed a human chain blocking the road. Shouting, “No justice, no peace,” they demanded that more minority employees and contractors be used on the Interstate construction project.

Like the brave men and women who fought for civil and economic rights before them, the people sitting on I-44 waited for the police. Some time later, a bus of officers in hardened riot gear appeared. The activists greeted the police legion loudly, “What do want? Justice! When do we want it? Now!” Arms linked in nonviolent resistance, they roared, “Shut it down!”

The police were spoiling for a fight, arrayed in military formation with shields and long wooden clubs. Their textbook plan was to knock someone off their feet with the shield, then work them over with their clubs. Within moments, the unconscious body of a young woman was beaten and lying on the road. When her friends approached to help, the police doused the lot with pepper spray.

The overt violence affected a few of the protesters who started to hurl insults back at the police. Organizers decided that it was time to withdraw. The SLPD in lines three deep followed behind. With each step they beat the pavement like some medieval war band out for blood.

As the crowd dispersed, it was clear that the activists controlled the pace and intensity of events that day. Goggles and dust masks on their heads or hanging around their necks, Ysaye Ellis and Chris Napier reflected while walking back. “The pepper spray was extreme,” said Ellis. “All we want is justice and they treat us like we’re prisoners.”

Later, when asked if the locations today – the Old Courthouse, the Martin Luther King Bridge, and the occupation of the Interstate near the location where the Interstate employment action took place – were symbolically significant, Aaron Burnett, a member of the Organization for Black Struggle, recognized that these were “historic sites of the struggle.”

He explained, “We are recreating that base that the movement left off in the 1960s.” The people are coming together for a common cause, “and when love for one another is the motivation they intuitively focus on a common work.”

If we reexamine the idea of a neighborhood, said Burnett, it isn’t about different ethnic groups as such. “It is about different ethnic groups coming together and recognizing this is about class.” He’s especially hopeful about the level of youth participation: They “are rising and saying enough is enough!”

Photo: A protester holds a sign showing the history of racism from the 19th century to the 21st, St. Louis, on Nov. 26. (velo_city/CC)

Comments