Super Bowl 50 – with its Peyton Manning/Cam Newton hype, the half-time show’s racial messaging, and the capitalist excesses you see in the advertising orgy – got me reminiscing, feeling nostalgic even. It brought me back to my own experiences playing football at a racially diverse high school and got me thinking about the paradoxical nature of the National Football League.

High school football on Chicago’s Northwest side

First, some reminiscences. Prior to high school, I played for the Kilbourn Park Cowboys, a team of Northwestsiders who represented that population – i.e. mostly white. My first year at Carl Schurz High School, the varsity team had three black players, six Latino players, and 27 white players. Interestingly, that year the Schurz Bulldogs had its first black co-captain, who, was, again, one of only three African American players on the team.

Schurz was probably the most diverse school on the Northwest side of Chicago, an area known as a bastion of white ethnic culture, especially back in the 1970s and 80s. The school’s racial and ethnic composition was closer to the city’s diverse, yet segregated population than most on the Northwest side at the time. So its lack of more minority players on the football team was a bit puzzling.

Years later, I found out why there weren’t more black players on the team. Many black alumni told me that they chose Schurz because it was a better school than the one in their neighborhood. Their priority was to escape the poor and failing schools in their segregated neighborhoods by any means necessary and to find refuge at Schurz. This was surprising to me since Schurz was not known for its academic prowess and had its own gang problems.

Most black students made long commutes, primarily the West side, to get to Schurz. Playing football was not their priority. Practices meant either getting up earlier or staying later than the average school day. With a long commute, lugging uniforms, and the physical exhaustion, these students faced bigger obstacles to playing.

Ten years ago, a Schurz teammate died from a heart condition. He was younger than me. He was a gentle giant of a man, always a smile on his face, though you could barely get away from his grasp and reach on the field. Another black teammate suffered a stroke and is now disabled. A Samoan, who went on to play college football, also has died. I have seen first-hand the devastating but undeniable truth that black men, and minorities in general, suffer more severe medical conditions and have shorter life expectancies.

I played football beyond high school and after I retired from the game I loved so much, I began to cherish more the camaraderie, lessons, and experiences I got from playing with a diverse group of people. Off the field they often treated unequally, but on the field we were equal. As the years go by, the X’s and O’s on Sunday gradually become less important as the memories become more valuable.

Race and the Super Bowl

All of this and more came flooding back as I watched Super Bowl 50. The game and the performances weren’t particularly memorable; it definitely did not live up to the new levels of hype. It was a defensive battle, which is usually not very exciting football. There was lots of sloppy play – dropped balls, bad penalties, and poor officiating.

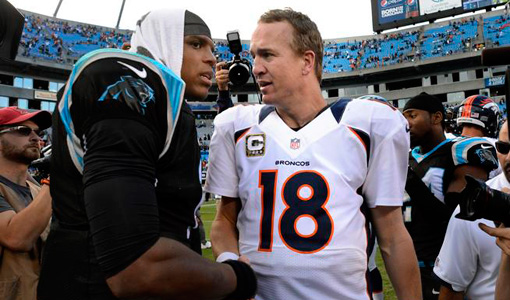

Of course, much of the attention was on the quarterbacks, the Broncos’ Peyton Manning and the Panthers’ Cam Newton. Manning, 39-years-old, in his last season, was trying to win one last Super Bowl. He was a sentimental favorite for fans looking to root for a team. On the other side, you had Cam Newton, a young superstar, former Heisman Trophy winner who has all the tools and more. Some of the “more” happens to be doing end zone celebration dances like the Dab, and being brash, things that apparently are a no-no for QBs, according to certain fans. Add to that, his poor performance during the game (like when he fumbled a fumble recovery) and during the post-game press conference (he came across as a sore loser) and you have a truly incensed fan base.

But Manning is white and Newton is black. That shouldn’t be important, but it is.

Only 20 percent of NFL quarterbacks are black, though roughly 60 percent of players are. Newton has been unapologetic about his behavior, claiming he hates losing. He has expressed the deeply-held belief, popularized by Knute Rockne and Vince Lombardi, which goes something like “show me a person who accepts losing and I’ll show you a failure.”

Being a sore loser in the NFL may not be appealing, but it makes sense. Teams want players who are offended by losing. Newton, however, seems to rub some fans the wrong way. And by some fans, it seems to primarily be white fans. They won’t look beyond the brashness, dancing, and abrupt post-game forced media appearance to see a talented player who celebrates when he’s happy and wears his frustration when he’s not. They won’t let Newton be Newton.

Newton has been quite honest and frank that he won’t bend to others’ expectations. While claiming he’s one of the best quarterbacks in the league who is black and that “may scare some people,” Newton acknowledges that the game is greater than him. And what those fans won’t look at, or accept, is that Newton is proudly black, as well as a generous person who leads a foundation that helps kids and communities. Yet, (white) fans even have a difficult time acknowledging his giveaway of footballs to kids in the stands after a touchdown, or the support he provides to his teammates.

And whether it’s hypocrisy or double standards at play, it seems no one (particularly white fans) conjured up Manning’s lack of sportsmanship when, in losing Super Bowl XLIV in 2010, he left the field before time expired. No handshakes. No customary congratulations to the opposing coach or QB.

Maybe we forget that recent piece of history because as much as we say we care about sportsmanship, we really don’t care all that much. We understand the desire and passion to win, as well as the deep disappointment and heartache of losing. Withdrawal can be understandable, unless you’re someone like Cam Newton. If you are Peyton Manning, and allegedly have some other baggage in your past, then you might get a pass. No such equal assessment seems afforded to Newton, though. He seems to be held to a different standard than other NFL QBs.

Socialist Football League?

The NFL is a living and breathing paradox. It epitomizes everything that’s wrong about America as well as what is best and what we aspire towards. The worst is the crass commercialism and juggernaut branding and marketing of a product that has exploited a labor pool who play a dangerous game.

Yet, paradoxically, American football fans don’t even realize that the game they love is fueled by a socialist model. Every team in the NFL equally shares television revenue. $7.2 billion split 32 ways puts $226 million in the coffers of each NFL franchise. It’s called parity, so each team regardless of market size has a fairly equal and good chance of succeeding. It puts them on a level playing field, so to speak.

Individual teams earn additional revenue through gate receipts, concessions, and merchandise. But the largest market teams like New York and Chicago are no better or worse, due to shared TV revenues, than the smallest market team, Green Bay.

That smallest market team also happens to be the only one that is owned by the people – its fans – who pay to be a Packer shareholder. Monetarily speaking, of course, the stock is essentially worthless. Packer shareholders are entitled to attend the annual shareholders meeting to vote for Lambeau Field board members, and to hear the non-profit board describe the state of the team on the eve of training camp. That’s about the end of the shareholder benefits. (Full disclosure: I’m a Chicago Bears fan and Packer shareholder due to my conservative Republican father purchasing two shares as a Christmas gift to me, a sort of novelty item).

The thing about the Packer ownership model is that it works. The smallest market of the 32-team league is also the 9th highest in local revenue, and this despite having only the 18th highest ticket prices. They sink their profits not into some mega corporation and shareholders, or line the pockets of some rich family or CEO, but put earned revenues back into the team and its facilities. Green Bay has the second largest stadium and the largest pro shop in the NFL.

American football is full of metaphors and paradoxes. The NFL is the most (slyly unannounced) socialistic framework and business model in all of professional sports. Yet it enjoys huge fan support and produces a financial windfall. It’s a microcosm of what we get wrong regarding violence, prejudice, and greed, and of what we do right regarding playing collectively as a team, and sharing some of the wealth to create equal opportunities for teams to succeed on a level playing field.

Hope is still in play.

Comments