SEQUIM, Wash – An unpublished manuscript “The Diary of Francis Marion Wheeler 1842-1899” has been gathering dust, unread, on a bookshelf in our house for many years.

Once I picked it up, I could not put it down. On Aug. 12, 1862, at age 19, he answered the call of Pres. Abraham Lincoln and joined the Union Army.

He writes, “Mother’s stories of the Revolutionary War, my admiration for the Revolutionary hero for whom I had been named, Francis Marion, ….greatly increased this feeling. I determined that my country should never in vain need my arm for assistance.”

The Civil War had been raging for a year, he writes with “numerous defeats and disasters” spreading “gloom and anxiety over the North.”

It became apparent to him “that the whole military power of the Nation, or the loyal part of it, must be exerted or the enemy would….surely succeed in disrupting the Union and establishing their confederacy. President Lincoln issued a call for 300,000 more volunteers…”

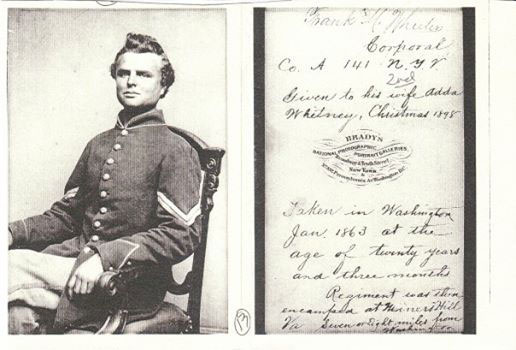

My Great Grandfather joined an infantry regiment Company A, 141 New York Volunteers. While stationed in Washington, D.C., he had his picture taken in the uniform of a corporal at a Matthew Brady studio. That image that has been part of my family as long as I can remember.

Great grandfather writes that he and his fellow soldiers marched in blistering heat, pouring rain, carrying a heavy musket, ammunition, and backpack.

He describes marching south in Virginia to the Rappahannock River. They bivouacked overnight. Then they were ordered to turn around and march back north to Manassas, tramping all night and the next day.

A train sent south to pick them up was empty on the way down and returned empty—a debacle that fueled deep anger in the ranks. In Manassas, they boarded the train. He was so exhausted he stretched out on the floor of the boxcar and fell into a deep sleep.

The train sped through Maryland, West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky and Tennessee. This was the famed emergency transfer of 30,000 troops, cannons, etc. ordered by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to reverse a defeat inflicted by the Confederates on Union Gen. Rosecrans in the Battle of Chickamauga.

Great Grandfather describes the trip as if it were a festive excursion. In Ohio, “Troops of rosy, laughing girls were to be seen at the depots,” he writes. “They frequently flung apples, flowers, and bits of folded paper containing mottoes among the boys….The good-natured engine drivers would sound the whistle vigorously several times before starting at which the stragglers would scamper back with commendable alacrity.”

Within hours of detraining in Chattanooga, they marched to the rear of Rosecrans’ army, a vast reinforcement that halted the Confederate advance. Later, he fought in the “Battle of Lookout Mountain.” It ended in victory for the Union Army.

They marched on to Atlanta, repeatedly engaging the Confederates. In a typical entry July 20, 1864, he writes: “We had a bloody and desperate battle. We were surprised and were not in line when the enemy was upon us. We had to form under fire. I shot a man close to me in the advancing line….It was in the thick woods….smoke concealed the enemy from us and us from the enemy. At sundown they withdrew leaving their dead.”

He was only a corporal yet he was assigned to command Company A because he was the highest ranking soldier still standing, he writes.

After the capture of Atlanta he marched with Sherman to the sea.

He writes, “Parties of soldiers foraged for themselves and messmates…Quartermasters’ men drove off cattle, horses and mules….plundered hen roosts, ransacked cellars, kitchens and pantries to the dismay and distress of the people who never thought of resistance as it would have been folly unspeakable to attempt it.”

He adds, “In short, the country through which we passed was exhausted and temporarily ruined. Railroads were torn up, piled and burned…bridges, depots and engine houses burned. Saw mills, tanneries, cotton gins, cotton presses, sugar mills….

“It was awful. My heart ached for the miserable people and I reflected on the years of toil that would be required before this lost property could be recreated.”

He adds, “One reflection however, showed me why all this evil had come on them. It was the remark of an old negro (sic) with whom I was conversing. Said he, ‘This property was not theirs. They never earned or cared for it. We earned it. It was ours.'”

He writes, “This was true. The masters had acquired it unjustly and it perished with a sudden and irreparable destruction.”

I found this passage remarkable. Here was a earnest young soldier, deeply religious, suffering pangs of conscience. And who gives him an insight into the meaning of that destruction? An African American, almost surely a slave who had freed himself and attached himself, like tens of thousands of other slaves, to the Union Army.

They captured Savannah, he continues, and then swung north marching into South Carolina. They crossed into North Carolina. On Mar. 24, 1865. He writes, “We entered Goldsboro, N.C. and joined there Schofield’s and Terry’s forces which had come up the river, Cape Fear, from the capture of Fort Fisher and Wilmington.

“Our appearance compared with that of the soldiers there encamped was striking. They were clean and but slightly sunburned, uniforms and equipment all new.

“We were unwashed, tanned, and grimed, our clothing worn, tattered and faded out. We marched with a rapid step, with ranks and files loosely closed. We were carrying pieces of bacon or undressed pork, fowls in our hands or adjusted to our equipage in some way. Coffee pots, frying pans, hatchets were freely exhibited…..

“Hence, our army entering Goldsboro was a singular spectacle. But it was formidable. They were all tried soldiers and were inured to tremendous exertions. At a word, they could bring their arms into position, dress the files, close their ranks and maintain every appearance of a disciplined army who knew their power and were proud of their record.”

A few days later, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, VA.

Greate grandfather marched in the victory parade in Washington D.C. a few weeks later. He writes, “……we passed in Grand Review through the streets of Washington, passing from Capitol Hill down Pennsylvania Avenue by the Presidential Mansion…..We filled the street from side to side…..as many men in double rank marched abreast as would fill the street across and this occupied a vista of about three miles which could be seen looking up Pennsylvania Avenue like a vast and moving mass surmounted the while by the glittering sheen of arms.”

He adds, “The infantry were several hours in passing, then artillery, cavalry, hospital trains, pontoon trains and last of all, ‘Sherman’s Bummers’ which created a great deal of merriment.”

In her great book “Reveille in Washington,” Margaret Leech ends with a description of that victory parade with Sherman’s army marching in the rearguard, blanket rolls across their shoulders, stepping with the easy slouch of soldiers who had marched thousands of miles, engaged in nonstop combat.

After the war, great grandfather became a Methodist preacher. He and his wife, Esther Sackett, and their children went to India as missionaries. It was an ordeal as difficult as the war. Great grandfather and his wife suffered heat strokes that ultimately killed her. Great grandfather remarried Esther’s sister, Adelaide. They moved to the Pacific Northwest with their children, including my grandfather, also Francis Marion Wheeler, where he continued his ministry.

Medical research had not yet identified “Post Traumatic Stress Disorder” but great grandfather suffered a mental breakdown that surely reflected the trauma he had suffered both in combat and in later life. He died in a mental hospital in 1900 at age 58.

A monument still stands at 15th & Pennsylvania Ave. in Washington D.C. honoring Sherman and his army. The scores of descendants should honor Francis Marion Wheeler as a hero. He fought to save our nation and end slavery.

Photo provided by Tim Wheeler/PW

Comments