HARTFORD, Conn. – Calling for $15 and the right to form a union without retaliation, fast-food workers in Hartford and New Haven walked off their jobs Thursday as part of a wave of strikes in more than 150 cities across the U.S. and protests in 33 additional countries on six continents. In all, strikes and protests reached more than 230 cities worldwide.

“I can barely afford to get by on the wages I’m paid,” said Kevin Burgos, who has worked at Dunkin’ Donuts in Hartford for over eight years and has three children. “Dunkin Donuts makes tens of millions of dollars in profits every year. The CEO makes nearly $2 million a year. Yet they are not paying me enough to survive, even after years of service.”

Workers went on strike at Hartford and New Haven major fast-food restaurants, including McDonald’s, Burger King, Wendy’s, and Dunkin’ Donuts. Clergy, elected officials, and community supporters joined the strike lines.

“These are our family, friends, and neighbors, and I am proud to stand with them in this fight to earn a living wage,” said Speaker of the House Brendan Sharkey, D-Hamden. “This is about putting a little extra in the pockets of struggling hardworking families, who will then spend that money in our communities, which in turn helps our economy.”

Members of Congress, including Rosa DeLauro, joined strike lines around the country and released a video declaring their support for the workers.

“Where Congress is failing to take action to address inequality, these workers are leading the way,” said Rep. Keith Ellison, D-FL-MN. “Their fight for $15 and a union is a shining light that will ultimately benefit all workers in the country and help lift up our economy. It’s clear this movement isn’t going to stop until fast-food companies listen to the voices of these workers, who are struggling to support families on as little as $7.25 an hour.”

In the U.S., fast-food workers went on strike in more than 150 cities from Oakland to Raleigh. Around the world, workers protested in 80 cities spanning nearly three-dozen countries, including Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Germany, India, Japan, Malawi, Morocco, New Zealand, Panama, and the United Kingdom.

Last week, workers and union leaders from dozens of countries met in New York City for the first-ever global conference of fast-food workers, organized by the International Union of Food, Agricultural, Hotel, Restaurant, Catering, Tobacco and Allied Workers’ Associations (IUF), a federation composed of 396 trade unions in 126 countries representing a combined 12 million workers.

“After coming together in New York, the commitment of fast-food workers to fight for higher pay and better rights on the job has grown stronger,” said Ron Oswald, general secretary of the IUF. “These unprecedented international protests are just the start of a worldwide campaign to change the highly-profitable, global fast-food industry. We’re putting the companies on notice: make real changes now, or this global fight is only going to continue to spread.”

A campaign that started in New York City in November 2012, with 200 fast-food workers walking off their jobs demanding $15 and the right to form a union without retaliation, has since spread to more than 150 cities in every region of the country, including the South-and now around the world. The growing fight for $15 has been credited with elevating the debate around inequality in the U.S. When Seattle’s mayor proposed a $15 minimum wage earlier this month, Businessweek said he was “adopting the rallying cry of fast-food workers.”

As it spreads, the movement is challenging fast-food companies’ outdated notion that their workers are teenagers looking for pocket change. Today’s workers are mothers and fathers struggling to raise children on wages that are too low. And they’re showing the industry that if it doesn’t raise pay, it will continue to be at the center of the national debate on what’s wrong with our economy. A study released last month by the National Employment Law Project showed that the recovery has created far more lower-paying jobs than higher-paying ones.

“Fast food is driving much of the job growth at the low end and the gains there are absolutely phenomenal,” said Michael Evangelist, a policy analyst at the National Employment Law Project. “If this is the reality, if these jobs are here to stay and are going to be the core of our economy, we need to make them better by raising pay. “

Not only do fast-food jobs pay so little that a majority of industry workers are forced to rely on public assistance, but many workers don’t even see all of the money they earn. Earlier this year, workers in three states filed class-action suits against McDonald’s alleging widespread and systematic wage theft, and a poll by Hart research showed 89% of fast-food workers have had money stolen from their checks.

Companies like McDonald’s are starting to realize they need to act. In response to the suits, the company said it was conducting a comprehensive investigation; while in a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, McDonald’s said a growing focus on inequality might force it to raise wages this year. And the spread of the movement across the world should cause further alarm. International fast-food restaurants are expected to expand at four times the rate of U.S. businesses, according to a recent Merrill Lynch report. And while US sales slump, companies like McDonald’s are relying on growth overseas to boost their bottom lines more than ever.

With shareholder meeting season upon us, and a recent report showing the industry has by far the largest disparity between worker and CEO pay, scrutiny on fast-food companies is bound to intensify. New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer said, “Excessive pay disparities pose a risk to share owner value,” and that conversations around inequality should move into the boardrooms of profitable fast-food companies. Meanwhile, USA Today called the growing worker movement, “the issue that just won’t go away” for the fast-food industry.

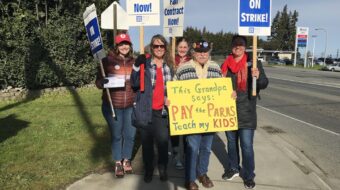

Photo: Jake May/AP

Comments