Book Review

“Left Out: Reds and America’s Industrial Unions”

By Judith Stepan-Norris and Maurice Zeitlin

2003, Cambridge University Press, 392 pages, paperback $37.99

American workers are justly proud when we read our great labor histories. The entire world celebrates our victories every May 1st, even though many North Americans don’t know why. Those of us who go to the trouble to study are usually stopped dead around 1947, when the great post-war strike wave tailed off. Whatever coverage we can find of American labor history after 1947 is mostly self-serving memoirs of individual unionists or union organizations. If someone really wants to know what happened, they ask the retirees.

I asked a number of retired union activists, and one child of a union activist, to help clarify a big mystery raised by the 2003 book, “Left Out: Reds and America’s Industrial Unions.” Apparently, not a lot of people have read it, and the fact that I got a free copy from an avid reader who had given up on finishing it tells why: there are too many charts and statistics. A 2004 People’s World review by Allan Stoehr reflects the problem. The reviewer, while happy to pass on the pro-communist view of most of the book, didn’t comment on the negative conclusions in the final chapter.

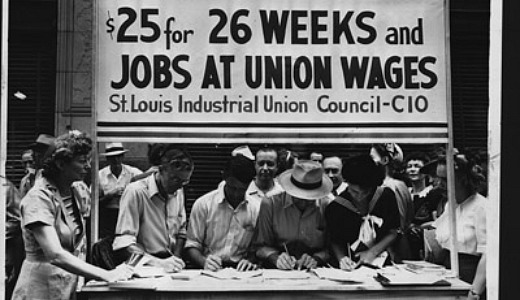

The almost endless charts and statistics are used by the authors to explain some really important research into the problems of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) from 1947 or so until it disappeared into a merger with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in the mid-1950s. From its first stirrings as the Committee for Industrial Organizing in 1935 until its end, the CIO represented the best of American labor. It redefined and invigorated the American labor movement and won the greatest victories, in the shortest time, that the American working class had ever seen. But what happened? In particular, Stepan-Norris and Zeitlin want to know what happened to the absolute best of those CIO unions, those usually described as “left-led.”

The two researchers divided the CIO unions into three categories: 1) Communist led, 2) anti-Communist led, and 3) unions that shifted between the Communists and the right wing of the labor movement. Using careful analysis of union contracts and other written data, they evaluated the unions in terms of their democracy, effectiveness in winning wages and benefits for their members, and the leadership’s ability to command the continuing respect of their members. In every contest, the statistics show that the Communist-led unions were the superior unions. For those of us who would like to see even more influence given to Communists in the trade union movement, the first three-quarters of the book makes sweet reading!

But the two authors then take their conclusions into the land of speculation. Those who have done their homework already know that the Communist-led unions were decimated after the CIO leadership took a strong right turn at the end of the 1940s. Stepan-Norris and Zeitlin, with very little supportive evidence, say that these excellent union leaders, still enjoying major support from their members, wanted to form a third labor federation, and would have, with certainty, had they not been forbidden by the Communist Party USA.

The authors go on to say that their third, Communist-led, labor federation would have been grandly successful. It would have gone on winning victories for the working class and the long downhill slide of American unionism (roughly 1957-1995) would never have happened. Presumably, American workers today would be enjoying excellent national health care, full civil rights and civil liberties, internationalist coordination, and all the progressive aspects of the old CIO, had it not been for the CPUSA’s restriction against forming a third labor federation.

That’s the mystery: did the most progressive union leaders of their day want to form a third labor federation and split the movement even further? If they had formed one, would it have been successful? If it had been successful, would today’s working class be better off than we are now?

Given the cruel fact that almost all American labor histories don’t even cover the period 1947-1957, or cover it in obviously misleading ways, the best way to solve the mystery is to go to the original source: ask the retirees! I checked with some of the most widely respected retired trade unionists alive today in the CPUSA, and here’s their unanimous conclusion:

1) They know of no intention nor effort by CIO union leaders to start a third federation.

2) If they had done so, under the conditions of those anti-Communist witch-hunt years, it would have failed.

3) Even if they wanted to and could have formed a viable third labor federation, it would not have helped the American working class, but rather would have split, divided and weakened us even more than we were. Communists, and Communist union leaders, always fight for the unity of the working class more than anyone!

In conclusion, “Left Out” is a book to be treasured because it offers real truth, backed up by research and facts, about this critical and under-reported period of American union history. The last part of the book is excellent, too, but it’s fiction.

Photo: http://www.niu.edu/~rfeurer/labor/chronological.html#LaborOrgRebelllate19thearly20th