Last week’s decision by the University of California’s Board of Regents to hike tuition has kicked off a new round in the long struggle between the university and the State of California over funding for the 10-campus system.

Overriding protests by students, professors, campus workers and Governor Jerry Brown, the regents voted 14-7 on Nov. 20 to raise tuition by as much as five percent per year for the next five years, unless the state ups its funding significantly.

If the decision is fully implemented, in-state tuition would rise from just over $12,000 now to over $15,500 in 2019-20, with out-of-state students paying nearly $45,000 in that year.

For weeks, UC president Janet Napolitano and other UC leaders had talked up the urgent need for an increase, with Brown countering that the university would be breaking its agreement to freeze tuition in return for more state funding.

In the lead-up to last week’s vote, students protested at campuses across the state. Last week they delayed the start of the regents’ meeting at San Francisco’s Mission Bay campus by blocking the entrance, continuing their protests inside and outside the meeting site.

The regents’ decision followed more than a decade in which funding cuts by the State of California have far exceeded modest increases.

In a statement, the Council of UC Faculty Associations blamed the governor for the tuition hike. In the 2001-2002 academic year, CUCFA said, tuition was just under $4,000, and the state provided $3.2 billion in funding ($4.4 billion in current dollars). When Republican governor Arnold Schwarzenegger slashed state funding, tuition soared to more than $11,000. CUCSA noted that after further cuts by Brown, a Democrat, current funding is more than one-third less in current dollars than it was at the start of the century.

The Faculty Association called on the governor to fund all public education, including UC, the California State University System and the community colleges at the 2001 level, and pointed out that such funding would cost the median California taxpayer just $50 per year.

The governor claims a tuition hike would break a four-year agreement that the state would provide more funding for UC in return for a tuition freeze, following passage of Prop. 30 two years ago. The last two state budgets have each increased UC funding by five percent.

UC officials deny such an agreement exists, and Napolitano charges that “massive state disinvestment” has made the tuition increase necessary, despite the recent modest rise in funding.

Students say they feel left out of the discussion by both sides.

Interviewed on Public Radio Station KQED Nov. 17, Kevin Sabo, chair of the UC Student Association’s Board of Directors, called on the UC administration to bring students into the decision-making process. He also pointed out that the State of California “needs a greater investment in UC, certainly more than four percent.

“This tuition explosion, as we’re calling it, certainly is a nonstarter for us,” he said. “And the UC needs to be better about the resources it already has.”

Use of resources was also an issue for the union representing over 22,000 service and patient care workers at UC’s 10 campuses. In a statement earlier this month, Kathryn Lybarger, president of AFSCME Local 3299, pointed out that the tuition hike comes when UC has given “pay increases as high as 20 percent to five of its highest paid employees,” with over 3,400 employees paid more than $250,000 annually. Lybarger also cited “millions of dollars” spent by UC on outsourcing custodial work “to contractors that pay their employees rock bottom wages with no benefits.”

She added, “The cost of these misguided priorities has already left UC facilities dangerously short staffed, and undermined the California Master Plan guarantee for thousands of qualified students in our state. Demanding more money from students and taxpayers without first correcting the tone-deaf mismanagement that has been a catalyst for UC’s financial problems is a nonstarter.”

As Governor Brown prepares his proposed budget and the state legislature debates funding through the first half of 2015, not just money but the very concept of public higher education in California will be at stake.

Testifying at the regents’ meeting, UC San Francisco professor Stanton Glantz, vice president of the Council of UC Faculty Associations, put the issue squarely: “You should not be arguing how much to raise tuition, but how to mobilize the public support to restore the California Master Plan of low-cost high-quality higher education for all … We call on you to fight to restore the California dream.”

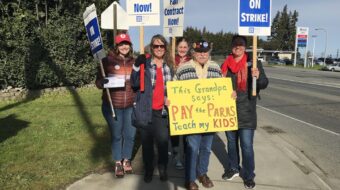

Photo: Students shout their disapproval after the University of California Board of Regents voted to raise tuition Thursday in San Francisco. Eric Risberg/AP

Comments