SEQUIM, Wash. – One late autumn afternoon – I believe it was 1950 – Clallam County Sheriff, Mutt Breece, arrived in his big blue Pontiac. He knocked at the door and my father answered. Breece was bringing a summons. My dad read the summons silently and handed it to mother standing beside him. I could see an expression of anger and alarm spread across Mama’s face as she read the document. Breece was a big, florid faced man but he didn’t look comfortable in carrying out this particular assignment.

A new word entered my vocabulary that day: subpoena. Daddy was ordered to appear before a Grand Jury in Washington, D.C. to answer the charges of an FBI stool pigeon that he was one of the hundreds of communists who had infiltrated our government in the nation’s capital. Indeed, these communists, according to the self-appointed guardians of national security had infiltrated every facet of American life from Hollywood to the local factories, not to speak of logging operations right in Clallam County.

Their “crime” was that they led the way in fighting for living wage jobs, unemployment compensation, racial equality, health care for all, 100 percent parity for farm produce. They were the best organizers of the workers and fought for union rights. And they were the most courageous fighters against fascism whether it was Franco fascism in Spain, Hitler and Mussolini, or home grown fascism right here in the U.S. That describes my father to a “T.” He was an anti-fascist.

He was a brilliant scholar, exacting in his scientific approach to reality. But he was also a visionary. He was born dirt poor in a tent, on a fruit farm on the banks of the Columbia in White Bluffs, Washington. He grew up to believe that the people would unite, African American, Latino, Asian American, Native American, and white. They would build a new civilization free of exploitation – socialism.

My father was to endure many forced separations, summoned to appear seven times before witchhunt hearings in Washington D.C., San Francisco, Seattle, and Tacoma in the years that followed. In fact, he had been blacklisted and that was the reason we were then eking out an existence on a dairy farm in Sequim, Washington.

None of those later subpoenas hangs in my memory more ominously than that first summons to Washington D.C.

He would cross the country on the train, being absent for more than a week to appear before the tribunal. He would refuse to testify no matter what questions the inquisitors asked. He was represented in that hearing by an eminent labor, civil rights and civil liberties attorney, David Rein. My wife Joyce and I got to know David and Selma Rein – as well as David’s partner, Joe Forer – 20 years later when I was assigned to Washington D.C. by the Daily World, now the People’s World.

Father left behind my mother, then caring for two infants in diapers, my little sister, Honeybee, and little brother, Nat. There was my elder brother, Steve, 13, my little sister Susan, then seven, and me, then ten. Twenty-five cows had to be milked twice daily, the herd fed, the barn cleaned. How did my mother, so small of stature, of such genteel birth, so burdened with young children, manage such an impossible task by herself?

Today, 64 years later, I still do not know. Daddy told us that the witch-hunters knew exactly the impossible situation we were in. “They calculated that I would crack under the pressure and cooperate with them.” They miscalculated.

Steve took on responsibilities far beyond his years. To add to his misery, Steve came down with flu, suffering terrible stomach cramps, fever, dizziness. Yet without complaining, he donned his boots, jacket, milking cap, and gloves, and went out to do the milking. I went with him.

Our grandfather, Bapa, in his eighties, came up from Bainbridge Island to help. He was an old man in failing health but still strong enough and lucid enough to help us stave off collapse.

An ice storm gripped the valley and the power went out. Our house, and more important, the barn and milk house, were without power. It meant no lights and no milking machines.

Steve and Bapa made an executive decision. We wouldn’t try to milk the cows dry. Just strip milk them enough to relieve the pressure on their udders. “Maybe the power will be back on tomorrow morning so we can milk the cows properly,” Bapa said.

No one argued. Bapa, Steve, and I hand-stripped the cows by kerosene lantern light that frigid night. Sure enough, the next morning, PUD managed to restore power and we milked the cows as they should be milked.

My father’s summons to appear at a hearing in Washington D.C. was front-page news. Before he left, the Sequim Press asked him if he wanted space to answer the charges and granted him an entire page to tell his side of the story.

He wrote an eloquent defense. I remember only one student spoke to me about the issue. Jerry McNamara, whose father worked for the U.S. Postal Service, came up to me before our class began one morning. “I heard about your father’s troubles,” he said. “I’m very sorry.”

We celebrated when Daddy returned. No one was more relieved than Mama. One evening after the barn chores were completed, after she had prepared dinner and we had eaten, Mama broke down. She had been holding herself together, grimly. Now she could give vent to her feelings and she did. She fell into bed weeping uncontrollably. We all gathered in the bedroom with her, trying to console her. I burst into tears. “Don’t cry Mama. Please don’t cry.”

So what did Mama do as tears streamed down her cheeks? She started to laugh. Yes! She burst into laughter seeing in our situation something so absurd, so ludicrous, what could you do but laugh?

Then Daddy started to laugh. And Steve, Susan, little Honey Bee, and Nat in their diapers. And I too began to laugh even as I wiped away the tears. We all had a great laugh together.

Years later, Mama told me, “When your father was subpoened and went away, I didn’t know if he would come back.” Those were the days when the Rosenbergs were on death row. The nation was caught in the grip of fear and hate.

One evening, three years later, we sat around our dining room table writing postcards to President Eisenhower urging clemency for the Rosenbergs. I remember the evening when the news came over the radio that the Rosenbergs had been executed. Mama’s dark, sorrowful, eyes filled with tears and she wept again.

The Rosenbergs could have lived if only they had bowed to the inquisitors demand, “Name names.” They refused to surrender. They were framed. They died for all of us. I loved them then and I love them still.

Our situation was to improve dramatically in the years that followed. We made many friends in the Sequim-Dungeness valley. Not least, we joined the Communist Party of Clallam County. We would never feel alone as long as comrades like the Gabourys stood with us.

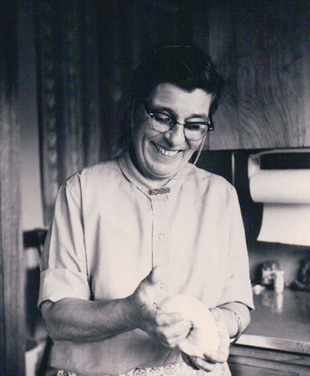

Yet in that terrible time, 1950, Mama was not immune to the fear. I saw her hands tremble when she rolled a cigarette. Even so, she stood her ground. She never left Daddy’s side. She did not flinch. She was Mother Courage.

Photo: Courtesy of Tim Wheeler/PW

Comments