“Americans have been constantly redefining their national identity from the moment of first contact on the Virginia shore,” historian Ronald Takaki wrote in his landmark 1993 book, “A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America.”

“Our diversity has been at the center of the making of America,” Takaki said. “America’s dilemma has been our resistance to ourselves — our denial of our immensely varied selves. But we have nothing to fear but our fear of our own diversity.”

What we need to do today, he wrote, “is to stop denying our wholeness as members of humanity as well as one nation.”

Takaki, a founder of multicultural and ethnic studies, died on May 26, just 9 days before our first African American president addressed the Arab and Muslim peoples of the world in, as the president noted, “the timeless city of Cairo.” I think the Japanese American historian would have been deeply moved by the president’s compelling “redefinition” of America’s identity.

Most of the commentary about President Obama’s June 4 speech at Cairo University — a speech televised and YouTube-ized across the globe — has focused on its immediate foreign policy implications and what Obama or others are going to do next week or in the coming months about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Iran, Iraq and Afghanistan.

But equally and perhaps more noteworthy for its longer-term implications was what Obama said about America itself.

As he did in March 2008 in his extraordinary speech on race in America, delivered at Philadelphia’s Constitution Center, President Obama in Cairo deepened and broadened what it means to be an American. It was a message of enormous significance, not just for the people of the Middle East and Muslims around the world, but also for Americans.

In Philadelphia last year, then-candidate Obama said, “I believe deeply that we cannot solve the challenges of our time unless we solve them together — unless we perfect our union by understanding that we may have different stories, but we hold common hopes; that we may not look the same and we may not have come from the same place, but we all want to move in the same direction — towards a better future for our children and our grandchildren.”

In Cairo, President Obama added another dimension. “Islam has always been a part of America’s story,” he said. “And since our founding, American Muslims have enriched the United States. They have fought in our wars, they have served in our government, they have stood for civil rights, they have started businesses, they have taught at our universities, they’ve excelled in our sports arenas, they’ve won Nobel Prizes, built our tallest building, and lit the Olympic Torch.”

There are nearly 7 million American Muslims in our country today, he noted.

Citing the 2006 election of Keith Ellison, an African American Muslim, to represent Minnesota’s 5th Congressional District, Obama continued, “And when the first Muslim American was recently elected to Congress, he took the oath to defend our Constitution using the same Holy Koran that one of our Founding Fathers — Thomas Jefferson — kept in his personal library.”

“As a student of history,” Obama said, “I also know civilization’s debt to Islam. It was Islam … that carried the light of learning through so many centuries, paving the way for Europe’s Renaissance and Enlightenment. It was innovation in Muslim communities that developed the order of algebra; our magnetic compass and tools of navigation; our mastery of pens and printing; our understanding of how disease spreads and how it can be healed. Islamic culture has given us majestic arches and soaring spires; timeless poetry and cherished music; elegant calligraphy and places of peaceful contemplation. And throughout history, Islam has demonstrated through words and deeds the possibilities of religious tolerance and racial equality.”

As he has so many times, Obama on the world stage redefined America and American patriotism much as Ronald Takaki did, as historians Boyer and Morais did in their “Labor’s Untold Story” and Howard Zinn did in “A People’s History of the U.S.,” as the American Social History Project did in “Who Built America?”:

“Just as Muslims do not fit a crude stereotype,” the president said, “America is not the crude stereotype of a self-interested empire. The United States has been one of the greatest sources of progress that the world has ever known. We were born out of revolution against an empire. We were founded upon the ideal that all are created equal, and we have shed blood and struggled for centuries to give meaning to those words — within our borders, and around the world. We are shaped by every culture, drawn from every end of the Earth, and dedicated to a simple concept: E pluribus unum — ‘Out of many, one.’”

Like those historians, he defined America’s history as an ongoing struggle for equality and social justice.

Last year in Philadelphia, Obama rejected “a politics that breeds division, and conflict, and cynicism.” He declared, “The real problem is not that someone who doesn’t look like you might take your job; it’s that the corporation you work for will ship it overseas for nothing more than a profit.”

In Cairo last week, the president linked Americans’ fears with those of people around the world. “I know that for many, the face of globalization is contradictory,” Obama told his worldwide audience. “The Internet and television can bring knowledge and information, but also offensive sexuality and mindless violence into the home. Trade can bring new wealth and opportunities, but also huge disruptions and change in communities.”

“In all nations — including America — this change can bring fear,” he said. “Fear that because of modernity we lose control over our economic choices, our politics, and most importantly our identities — those things we most cherish about our communities, our families, our traditions, and our faith.”

“But I also know that human progress cannot be denied,” he said. “There need not be contradictions between development and tradition.”

Development, he said, cannot be “sustained while young people are out of work.”

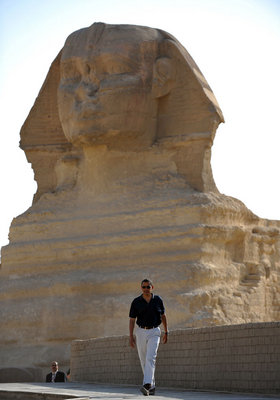

If he did nothing else with his Cairo speech, if these observations — and the words and images of the American president paying respect to the ancient civilizations and cultures of the Arab and Muslim peoples, a tall skinny American standing dwarfed by the Sphinx and the pyramids at Giza — cause Americans to come to a wider and deeper view of what it means to be American and our place in the world, then his speech will have accomplished something quite profound.

suewebb @ pww.org

Comments