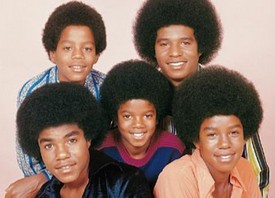

I think the first album I ever bought was by the Jackson Five. It was at a record store on Hillman and Kenmore Street in Youngstown, Ohio, and I rushed home to jam to the bubble gum beat and the saccharine sound of Michael Jackson.

Today, neither the store, the vinyl LPs, nor Michael Jackson exist.

Over the years I’ve grown an accustomed to the absence of the store: everything that surrounds it is gone too: the Arab grocery owned by the notorious Rafiti brothers, Willie Mae’s Soul Kitchen, the body shop whose rusted shapes once adorned the corner. Even Hillman Jr High School, where young women endlessly debated who was the “finest,” Tito, Michael or Marlon, is no longer there though the worn-and-torn brick structure remains.

The LPs gave way to eight track tapes, cassettes, CDs and they to MP3s – and I missed them not all that much.

I wonder, however, if I will ever get used to the absence of Michael Jackson.

It’s not that I ever was a big Michael fan. I was always more of a funk man myself and quickly grew to disdain, at least officially, the Jackson sound. But the Jackson sound, honed in not too far away Gary and later in Berry Gordy’s Motown studio in Detroit, in many ways defined me and my generation and several sets of other generations in deep, profound and even troubling ways.

The music, like Stevie Wonder’s, is almost omnipresent: always hummed, within reach, the lyrics part of the body’s genetic memory. Michael’s style and stories are almost omnipotent, cross-cultural urban legends, toying with the aspirations of hundreds of millions of working-class poor black, brown and white youth, defining, teasing and tossing them through the decades of Generation Me, Generation X and Generation Y as jobs disappeared, towns collapsed and dreams fell in on themselves or went up in the mist of all too many crack pipes.

And then there was the dark side: not so much in ‘Thriller,’ but in stories of an over-ambitious and cruel father, an ambiguous identity, a bleaching of personality, texture and tone, with surgeries and dyes and fashions woven one wondered where: Paris, New York or the laboratories of 1930s Germany? One watched in, yes, almost horror as a little boy with round nose and full lips became transformed into what or whom? Peter Pan? Diana Ross? Elizabeth Taylor? Who?

The rumors, surely some slander, and the charges bounded through the years, with cash settlements settling nothing. Even the most hardened stomachs retching with the notion of abused children and ruined lives.

Was this the price of wealth and fame: Oz and infamy, sunglasses, veils and white gloves? And what lay below? Surely a great, even transcendent artist and performer, a musical genius, but also the same black child born into a Gary Indiana of unions and steel and fire and Smokey Robinson; a proletarian child and pauper turned prince, who thought perhaps for a price he could have it all.

But with Michael gone and Gary’s mills all but closed and also Motown’s General Motors, Chrysler and maybe even Ford, I wonder at what price?

I remember hearing in Cape Town once how Michael had come and tried to buy Table Mountain, staggered by its beauty by the sea and thinking that he could own it, not only it the mountain but also perhaps its beauty, perhaps also its dream.

“How could he think that we would sell such a thing, our Table Mountain?” I was asked. I had no answer: only a pang of hurt and angst not at Michael, never Michael, but at the illusionary pursuit of the bourgeois dream.

As I mourn Michael, I mourn the Lost throughout the years, but also relish and wonder at the Found. I also wonder what he was chasing. Maybe Michael thought he’d find it on a mountain. I hope he does. I say with Baldwin: Go tell it on a mountain, Michael; Go tell it on a mountain! But remember it’s not for sale.

Comments