Melva Norris, widow of Clarence Norris, the last survivor of the Scottsboro prisoners, died recently at age 82, 21 years after her husband died in a Bronx hospital.

Thanks to the struggle of Communists and their allies, Clarence Norris lived more than 60 years after he and eight other Black youth were arrested and charged with the rape of two white women on a train in Scottsboro, Alabama.

What really happened in Scottsboro in 1931? In the early Depression, black and white youth “rode the rails” or “hoboed,” often following rumors of jobs in faraway places, in a desperate attempt to find work. In this case, after a white youth came onto the train and stepped on the hand of a black youth, a fight erupted between white and black youths. The blacks outnumbered the whites, who fled from the train at the next stop.

They told the stationmaster that they had been attacked by blacks and he wired this information ahead. A racist posse was then organized and deputized, rounding up nine black youths, tying them together, putting them on a flat bed truck, and bringing them to jail in Scottsboro. Two white female mill workers and part-time prostitutes spoke to the posse. One of them, Victoria Price, claimed that they had been raped by the blacks. She subsequently identified six of the nine as her alleged attackers.

Fortunately, the new governor of Alabama, B. M. Miller, a fiscal conservative but longtime enemy of the Klu Klux Klan (he had been defeated by Klan-backed candidates in the past) sent in National Guard troops to keep the nine from being lynched by a crowd which had gathered for that purpose.

A trial was then held, the first of many. The nine included Roy Wright, a 12-year-old. The “defense” lawyers failed to adequately cross examine the two young women (whose specific testimony was contradictory) and called no witnesses except the nine defendants, who simply tried to tell what they thought had happened as best they could. The “defense” did not even make closing arguments to the jury.

Eventually, eight were convicted and sentenced to death. The ninth, Roy Wright, got a mistrial because one of the 12 jurors refused to sentence a 12-year-old to death.

The NAACP, representing African American small business and professional interests and fearful of involving itself in rape cases, initially did nothing. The International Labor Defense, a workers’ defense organization led by Communists, took up the case.

The ILD literally saved the Scottsboro defendants’ lives, although the struggle would be long and hard and there would be many errors and reversals.

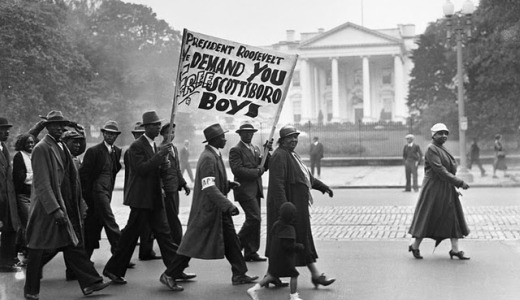

Communists made the case both national and global, organizing demonstrations and petitions throughout the U.S. and the world to save the nine, the first time that racist oppression in the U.S. had been opposed on such a scale. Communists also organized rallies which brought African Americans and whites together at the grassroots level for the nine. Mothers of the defendants participated in rallies and tours both here and abroad. In Germany, Communists organized and Nazis sought to terrorize demonstrations on behalf of the nine. Ruby Bates, one of the two young women, changed her story and joined the defense campaign.

The ILD also hired a distinguished constitutional lawyer, Walter Pollak, to appeal the case. Pollak’s abilities, and the arrogance of the state of Alabama’s representatives, led the Supreme Court in 1932 to overturn the convictions based on the clear violations of the due process clause of the constitution. But that was only the beginning.

The ILD then employed a famous flamboyant New York criminal attorney, Samuel Leibowitz, to represent the nine at the new trial. Although Leibowitz was in no way involved with the CPUSA and the left (his connections were with the New York Democratic machine and he was very much of an anti-Communist), he was the subject of savage and relentless red-baiting and anti-Semitic attacks in and outside of the court.

As the cases developed, Leibowitz showed the clear policy of excluding all African Americans from jury pools, although of course, all of the juries remained all white. The racism and anti-Semitism which prosecutors and witnesses poured out at these trials was a sort of synthesis of lynch mobs and storm troopers.

In 1935, a conservative-dominated Supreme Court made a landmark ruling in Norris v. Alabama, reversing the conviction of Clarence Norris on the grounds that there had been no blacks in the jury pool.

A new round of trials then began, with Victoria Price as the sole complainant (something that in itself, given the distortion of the earlier cases, would have led prosecutors anywhere outside the segregationist South to drop the case). In the new trials, one African American served on the grand jury indicting Haywood Patterson, the first African American to serve on any Alabama jury since Reconstruction. Patterson was sentenced to 75 years in prison. Clarence Norris was subsequently sentenced to death.

In what was then the Popular Front period, the ILD formed a coalition with the NAACP and the American Civil Liberties Union to create the Scottsboro Defense Committee. In 1937, the committee agreed to a compromise which many left students of the case still strongly criticize – a compromise in which four of the nine had all charges dropped against them and five, including Norris and Patterson, the best known of the nine, were sentenced to long prison terms. The governor of Alabama at the time, Bib Graves, offered to pardon the remaining five as he was about to leave office in 1938, if they admitted their guilt, but they refused. Eventually, four were paroled over the next 13 years.

Scottsboro was, in political terms, the most important victory won by anti-racist activists in the U.S. since the Civil War. The nine were not lynched and the campaign raised the consciousness of people throughout the world to the realities of U.S. segregation and lynch law.

But there was little individual joy for the nine – especially the five who were convicted in farce trials.

Haywood Patterson, the most famous of the nine, escaped in 1948 and fled to Detroit. When Patterson, who was like the others illiterate, dictated a book to a journalist which was published as “The Scottsboro Boy” in 1950, the FBI arrested him, but G. Mennen Williams, the pro-labor governor of Michigan, refused to extradite him. Tragically, Patterson was later involved in a bar fight in which he killed a man. Convicted of manslaughter, he died of cancer in a Michigan prison shortly afterwards.

Clarence Norris was paroled first in 1944, returned to Alabama for parole violations, and paroled again in 1946. He fled Alabama again and led a hand-to-mouth existence, at one point getting a job in New York as a dishwasher with the help of his old lawyer, Samuel Leibowitz. Norris went through two broken marriages and petty crimes before beginning in the 1960s to get his life together. Then, in the context of the civil rights movement, he began to fight to get a pardon from the state of Alabama (technically, he was still in danger of extradition).

With extensive aid from the NAACP (aid that would have been welcomed 45 years earlier) he was finally pardoned – by Gov. George C. Wallace in 1976, after Wallace had moved away from the lost cause of segregation and disenfranchisement which he had had championed through the 1960s.

Norris died in a Bronx, N.Y., hospital in1989 after years of suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. His widow passed away April 24.

The Scottsboro case of course will not pass away, at least until all forms of racist oppression have been buried here and everywhere.

Without the Communist Party USA, the triumph that Scottsboro represented, not a simple triumph but a triumph nevertheless, would have been impossible. Had the postwar world been different, the lives of Patterson particularly and Norris might have been different. Today, we can learn from Scottsboro what the CPUSA, or for that matter other groups committed to militant activism, seeking to both unite and educate masses of people, can accomplish under the most extreme circumstances. And we will have need for such focused activism today and tomorrow if we are to defeat the forces of racism and reaction and unite the people in the struggle for social justice and peace.

Photo: http://civileyes.blogspot.com/2010/03/scottsboro-boys-of-alabama.html /preservationnation.org

Comments