Hundreds of students, teachers, parents, staff members, and allies packed Chicago’s Fuller Park Fieldhouse Thursday night to inform representatives from Chicago Public Schools that they will not accept the closure of nine public schools in the diverse, working-class neighborhoods around Bridgeport, Kenwood, and Back of the Yards.

The meeting was filled with inspiring displays of solidarity: parents fighting back tears as they spoke of schools that had become linchpins of their communities; students pleading with CPS to let them keep these places where they feel safe, respected, and challenged; teachers telling of students with special needs who, in their classroom, had said their first word, read their first book, or written their name for the first time.

Take, for example, George B. McClellan Elementary, a school in the Bridgeport neigborhood. CPS is considering McClellan for closure, calling it “underutilized.”

Student Kamyra Parks, 8, took a moment away from her friends to grant People’s World an interview. Her verdict? “My school is perfect.”

Kamyra’s mother, Robyn Parks, says she was shocked when she got the news that CPS wanted to close McClellan.

Ms. Parks, like other public school advocates, speaks of McClellan as a vibrant institution that has mobilized massive parent and community support on behalf of its students, over 25 percent of whom have special needs.

Ivette Gaston, a community representative on the Local School Council and parent of three McClellan honors students, dismissed CPS’s allegations: “When they say underutilized, we don’t understand, because we are literally turning closets into space for special needs students.”

Bozena Brogan, the parent of a McClellan student with autism, went to her Local School Council to ask for a “sensory room,” a space with the resources to help autistic students manage the difficulties that arise in a classroom setting.

Together, Gaston and Brogan made it happen, scrubbing floors and painting murals to transform a closet into a soothing environment with soft lights, crash mats, a trampoline, and toys. Another closet holds a speech therapy room; the basement has been converted into an art room and a dance studio where members of the Joffrey Ballet introduce students to the art of movement.

For Bozena Brogan’s daughter, these initiatives have been profoundly important. For the first time, Brogan says, her daughter talks about having friends.

Stories like this show the human cost of school closures and suggest that McClellan is anything but underutilized. As parent Josephine Norwood puts it, “this is not about underutilization, it’s about miscalculation.”

The McClellan community argues that CPS inaccurately evaluated the capacity of the building, where a number of classrooms devoted to special education are capped by law at 10-13 students, depending on age.

Instead, Norwood says, CPS has calculated capacity on the assumption that all classrooms should hold 31 students. Defenders of McClellan say that rectifying this error would show that the school is operating much closer to full capacity.

Norwood’s son has already had to change schools twice because of closures, and she has no intention of letting it happen again.

So will the tenacious Bulldogs of McClellan Elementary manage to save their school?

Principal Joe Shoffner cited the mobilization of the community as cause for optimism. “There are signs that they’re listening,” he says, “and if they hear us, we’ll be OK.”

Ultimately, however, it’s not just a question of saving McClellan, or Sherman, or Parkman, or any one school among the 129 that CPS is considering for closure.

The stakes are much higher, and the people gathered here and in similar venues across the city say they’re fighting to save every public school in every community in Chicago from a corporate-funded attack on public education.

Their unanimous message was clear in the chant that broke out from time to time: “Save our schools! Save our schools! Save our schools!”

Alison Moulton, a 5th grade teacher at Hamline Elementary, says her school isn’t on the list of “underutilized” campuses. She came out in support, she says, in hopes that “they’ll see that a school is more than just a building.”

Thomas Tobbe, a member of the Young Communist League, says his group has gotten involved because school closings are an attack on working people:

“We’re here because this is, first and foremost, a class issue. Working people pay for public schools with their taxes, they support public schools with their involvement, and now their children’s education is being compromised. The YCL will fight these closures in solidarity with teachers, parents, students, and allies in the community.”

This fight is just beginning, and a uniformed Chicago police officer working security at the event summed up the fighting spirit that the people of Chicago bring to the defense of public education:

“Give ’em hell in there.”

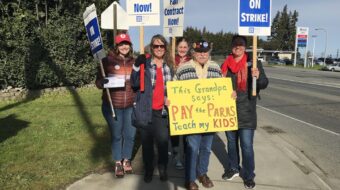

Photo: Earchiel Johnson/PW

MOST POPULAR TODAY

Zionist organizations leading campaign to stop ceasefire resolutions in D.C. area

High Court essentially bans demonstrations, freedom of assembly in Deep South

Afghanistan’s socialist years: The promising future killed off by U.S. imperialism

Communist Karol Cariola elected president of Chile’s legislature

Comments