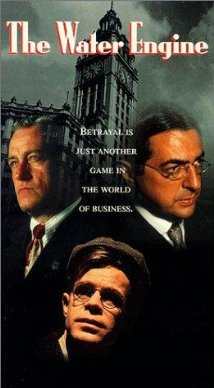

The Water Engine opens in the red glow of flames from a factory furnace, while workers operate drill presses and grinding wheels in a shower of sparks. Among these laborers we find veteran character actor William H. Macy, who plays a brilliant, if awkward and unassuming machinist.

The setting for this 1992 film is Chicago, and the time is 1934, where the World’s Fair is in full swing. The fair, hailing “A Century of Progress,” attracts patrons to the displays of marvels, but not far away, in a discreet lab, our hero constructs an engine that runs on tap water.

The script comes from the pen of David Mamet, and the dialogue often reflects the tense bursts associated with his style. It also features wonderful performances from a number of reliable players.

John Mahoney is excellent as a skeptical, bemused, and later nervous, patent attorney. Joe Mantegna is even better as a highly polished corrupt slug who promptly informs our hero that a good case could be made that the machine he created actually belongs to the company where he is employed, since it was built with some tools he pinched from the workplace, and thus he informs the inventor that he is just as likely to end up in jail as he is with a patent to a world-changing device.

As he trudges between his factory job, his hand-built laboratory, and his small apartment that he shares with a sister recently blinded in an industrial accident, Macy alternately passes a billboard touting the American ideal and its proclaimed “world’s highest standard of living,” and a speakers platform. The platform plays host to a parade of men and women who harangue small crowds with vaguely socialist speeches.

The film quickly turns dark, as those who wish to buy, steal or destroy the device close in, and our humble machinist casts about, looking to save his invention as well as his skin.

The Water Engine properly gives the lie to the capitalist myth that hard work and ingenuity will be rewarded with riches and fame. The truth is that for every innovator who strikes it rich, there are a legion of dreamers and inventors who wind up swindled, heartbroken, and left on the side of the road by the monopolists who control not only the economy, politics, press, and judiciary as well.

Comments