MEXICO CITY – Just before judges heard testimony on migration at the Permanent People’s Tribunal in Mexico City two weeks ago, the Mexican government announced a new measure that might have been deliberately intended to show why activists brought the Tribunal to Mexico to begin with, three years ago. Interior (Gobernacion) Secretary Miguel Angel Osorio Chong told the press that the speed of trains known by migrants as “La Bestia” (The Beast) would be doubled.

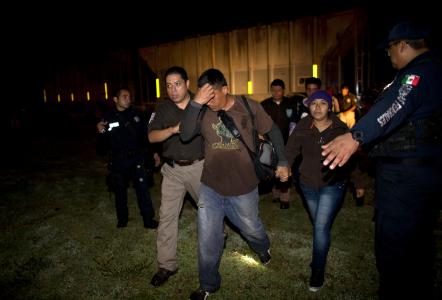

Photos of “La Bestia” have become famous around the world, showing young migrants crowded on top of boxcars, riding the rails from the Guatemala border to near the U.S. It’s a slow train, but many boys and girls have lost arms and legs trying to get on or off, and wind up living in limbo in the Casas de Migrantes — the hostels run by the Catholic Church and other migrant rights activists throughout Mexico. Osorio Chong said Mexico would require the companies operating the trains – a partnership between mining giant Grupo Mexico and the U.S. corporation Kansas City Southern – to hike their speed to make it harder for the migrants.

In the Tribunal, young people, giving only their first names out of fear, said they’d see many more severed limbs and deaths as a result, but that it wouldn’t stop people from coming. Armed gangs regularly rob the migrants, they charged, and young people get beaten and raped. If they’re willing to face this, they’ll try to get on the trains no matter how fast they go. “Mexico is a hell for migrants already,” fumed Father Pedro Pantoja, who organized the Casa de Migrantes in Saltillo.

Outrage wasn’t limited to the Tribunal hearings. Former Mexico City mayor Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, now the head of one of Mexico’s left parties, the Movement for National Renovation, asked, “How can the government keep them from freely moving through Mexico, when they’re trying to stay alive, and find work so their families survive?” If Osorio Chong really wanted to reduce migration, he told La Jornada, Mexico’s leftwing daily, “he’d support the farmers, so that people have work and don’t have to leave to seek life on the other side of the border.”

While the Tribunal hearings offered an insight into the way the Mexican left sees migration to the U.S. and Canada, the Tribunal itself is an international institution based in Rome. It was first organized by the British philosopher Bertrand Russell to investigate U.S. war crimes during the Vietnam War. Since then it has held hearings about the violations of human rights during the “dirty wars” under the military dictatorships in Latin America, as well as in the Philippines, El Salvador, Afghanistan, East Timor, Zaire and Guatemala.

In 2011 the Tribunal announced it would hold hearings in Mexico on a wide spectrum of issues, including attacks on unions, farmers, the environment and women. Of them, the hearings on migration have been the most extensive, including three pre-hearings in Mexico, three in the U.S., and a weeklong debate at the national autonomous university (UNAM). Bishop Raul Vera declared at their start, “We are experiencing the breakdown of the social order and the militarization of the fight against drugs [and] actions imposed by a state whose leaders are full of ambition, where it is not political proposals that count, but business and theft.”

For many Mexican migrant rights activists, the most serious violations are committed against migrants passing through Mexico. In August of 2010 seventy-two people were found massacred outside San Fernando, a small town in northern Mexico. All were migrants passing through Mexico, and had been kidnapped and murdered. The following April 193 bodies of migrants were discovered in 47 graves. Many were Central Americans, but others were Mexicans. In May of 2012 another 49 graves were found.

While the perpetrators of these crimes were, according to Tribunal testimony, members of drug cartels and their paramilitaries, the accusation submitted to the judges charged the Mexican government was ultimately responsible. Not only did the government fail to protect migrants, knowing that they were being kidnapped regularly for extortion, but it did not recognize their right to migrate at all, treating them instead as criminals. “All these acts are the predictable and preventable result of its policies and actions,” emphasized Mexican academic Camilo Perez at the hearing’s start.

Judges urged to examine causes

He urged the judges to use the massacre in San Fernando as a lens through which to examine the causes of migration and the reasons for the vulnerability of migrants. “Government policies actually depend on migration at the same time it criminalizes migrants,” he cautioned. “The responsibility is structural, not just the actions of individuals.”

Raul Ramirez Baena testified before the Mexico City hearing by Skype from Mexicali, the capital of Baja California, just across the border from California’s Imperial Valley. Ramirez Baena, Baja’s former human rights prosecutor, argued that U.S. border enforcement policies were also linked to violence against migrants south of the border.

“U.S. border enforcement really got going when NAFTA took effect in 1994,” he explained, “and national security became a major justification, even extending U.S. authorities’ reach to Guatemala. At the same time, it established a policy of deportation, which made the problems of poverty and gangs here worse. Then Mexican government militarized the Mexican side, using the war on drugs as a pretext. The killings and kidnappings in northern Mexico are a consequence of this joint policy.”

There was something very Mexican about focusing on the situation of Central American migrants passing through Mexico. In one way it highlights a generosity of spirit – “their situation is worse than ours” – and responds to the extreme brutality of kidnapping and murder. But it also reflects the way Mexicans, especially on the left, have looked at the migration of their own countrymen. Historically, many leftwing activists saw those who left for the U.S. as people who had abandoned the struggle for social change at home. In addition, they sometimes argued, migration relieved the social pressure of poverty on the Mexican government.

Yet at the same time, Mexican political activists have not only come to the U.S. (sometimes fleeing repression themselves), but they’ve become increasingly outraged by the treatment Mexicans get there. And the increase in migration has been phenomenal. Today there is no town in Mexico so isolated that people haven’t left for the U.S., and to which dollars now flow from those working in the north. The most important achievement of the Tribunal, therefore, was not just assigning responsibility for the violence, but digging into the reasons and responsibility for the migration itself.

According to the conceptual framework established at the beginning of the hearing by Ana Alicia Peña Lopez, an economist at UNAM, “Mexicans and Central Americans are forced to leave home because of their precarious economic and social conditions. These are the product of neoliberal reforms, especially the free trade treaties implemented in Mexico and the rest of this region.”

Peña Lopez listed several changes in migration in the free trade era — most important, its massive size. In 1990 4.4 million Mexican migrants were living in the U.S. At the beginning of the economic crisis in 2007 it was 11.9 million and in 2013 it was still 11.8 million. In other words, jobs in the U.S. might have been harder to find, but people didn’t go home because the conditions causing them to leave hadn’t changed. Money sent home by Mexicans reached $27 billion by 2007, even during the crisis.

But, she also noted, migrants now include women, young people, indigenous people and even children. “Employers take advantage of this to lower their labor costs,” she charged. “Criminalizing migrants hasn’t simply led to the violation of their rights, but has made their labor even cheaper. And Mexico pushed this process, through reforms that lower wages and make jobs less secure, that drive rural communities off the land to enable mining and energy projects, and that put basic services like health and education out of the reach of more and more people.”

The Tribunal’s report on migration will be presented to another set of judges in November, where it will be included with those on other human rights issues. The tribunal has no power to bring legal charges against the Mexican, U.S. or Canadian governments over human rights crimes. But it can focus international attention on violations, and create a climate in which progressive jurists can try to use their own legal systems.

Throughout Latin America, in the wake of military dictatorships and civil wars, truth commissions were established to counter the culture of impunity – that governments can jail and murder people with no consequences for those who give the orders. Mexico has never had such a commission, nor has the U.S. or Canada. The Tribunal hearings certainly found evidence and witnesses that testify to widespread abuses, and provide an argument for further proceedings with more formal consequences.

But to Andres Barreda, another UNAM economist involved in setting up the hearings, the ultimate goal is also to ask Mexicans themselves what direction they choose for their country. “Trade agreements and economic reforms have undermined Mexico’s national sovereignty, and led to its economic and political subjugation to the United States,” he says. “Mexico has a right to a national economic system that protects sovereignty and autonomy, and therefore places the needs of its people before the profits of corporations and an economic elite. Unless we face this, we can’t resolve the situation of migrants, whether our own or those passing through Mexico.”

David Bacon was one of the judges in the PPT hearing in Mexico City.

Photo: Mexican police escort migrants attempting to reach the U.S. off “La Bestia.” Rebecca Blackwell/AP

Comments