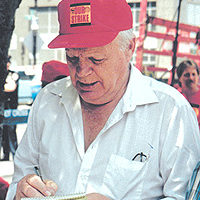

Ryo Kumasaka was playing touch football in a nearby playground on December 7, 1941, when he heard Japanese planes had bombed Pearl Harbor.

“It was incredible – beyond belief,” he told me in a recent interview. He said his family tried to make sense out things later that evening. “We agreed to continue with our lives, which meant that I would continue to attend classes at the University of Washington.”

Kumasaka said he did not notice much hostility among his class mates even as they gathered in the library to listen to President Franklin Roosevelt ask Congress to declare war. “There was lots of excitement but no hostility,” he said.

But that was to change. Newspapers up and down the West Coast, taking their lead from the San Francisco Examiner, began running front-page stories demanding evacuation of all Japanese, citizen and non-citizen alike. The die was cast in February when President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066.

The order authorizing the Secretary of War to determine areas “from which any or all persons may be excluded,” set in motion a process that saw more than 110,000 men, women and children of Japanese ancestry relocated in 10 concentration camps.

Kumasaka, was one of them. On May 15, 1942, he, his mother, father and younger brother together with 1,500 other Japanese, some of immigrants, others born in the United States were herded onto the train, with only those personal belongings they could carry.

After a three-month stay in the Pine Dale relocation center the family was sent to the Tule Lake concentration camp near the California/Nevada border. “Accommodations were minimal,” Kumasaka remembers, “An entire family crammed into a room 20 feet square. We ate in a community mess hall and shared bathroom facilities.” He said many of the elderly people had a hard time adjusting to the food that “wasn’t what you would call ‘Japanese cuisine.’”

Although he suffered many indignities, the change of his military draft classification from “1-A” to “4-C” still rankles. “I was classified an ‘enemy alien’ – me American who was born in the United States!”

Kumasaka had a two-word reply when asked about the recent claim by Rep. Howard Coble (R-NC) that the round up had benefited those sent to the camps. “That’s bull,” he snapped.

Unlike many internees who remained in the camps until 1946, Kumasaka left Tule Lake in December 1942 to live with his brother in Chicago. From there it was to Denver where his family eventually joined him. He was reclassified “I-A” in late 1944 and spent the waning days of the war in the army.

Now 83 and retired, Kumasaka lives in a Seattle suburb and plays an active role in the Alliance of Retired Americans. “When they sent us to the concentration camps hardly anyone spoke out in our defense,” he said as our interview wound down. “That has changed and today there is a growing resistance to laws like the Patriot Act. We may not be winning yet, but we will win.”

The author can be reached at fgab708@aol.com

PDF version of ‘Will history repeat itself? An interview with Ryo Kumasaka’